Iceland is not exactly associated with walruses or polar bears, although the island is considered the gateway to the Arctic. But while polar bears stray onto the island from time to time, walruses have no connection with it. But that wasn’t always the case, as an international research team has now discovered. Even at the arrival of Vikings 1,100 years ago, there existed a separate population of walruses around the island. But the new residents were probably not good neighbors according to the research results.

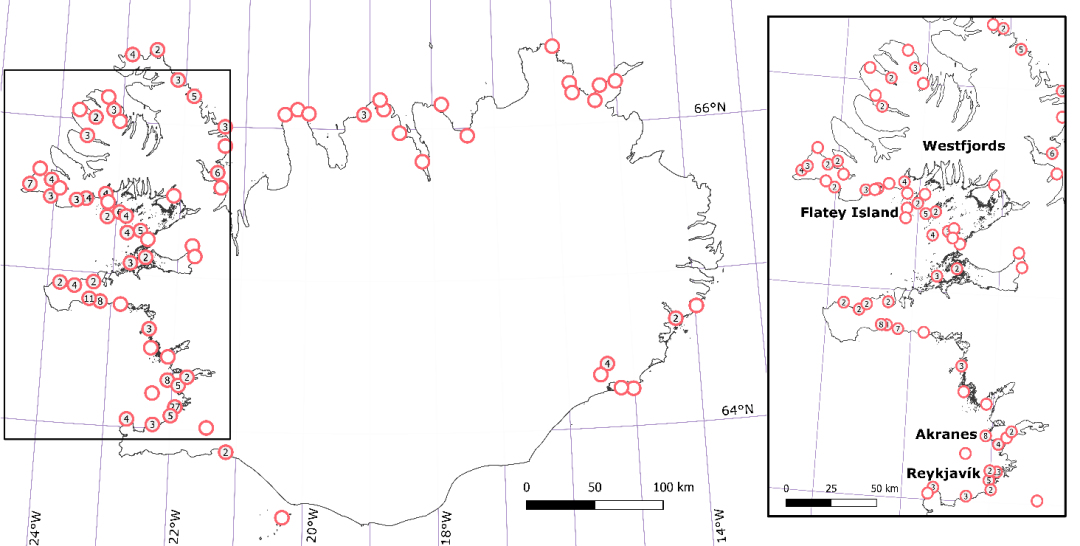

The Vikings, who according to tradition arrived in Iceland in 870, were farmers and traders in search of new livelihoods. And apparently the island in the middle of the North Atlantic was perfect for it. For the walrus ivory trade was one of the mainstays of this fabled Norse culture. It has long been known to researchers that walruses must have lived around Iceland. Norse remains and lore had testified to this. But now an international team of scientists has combined different methods and discovered something astonishing. By analyzing old and new walrus DNA, carbon-14 analyses, and closely examining ancient sources on the place names of the remains and the corresponding references to walrus hunting by the Norse, researchers led by Xénia Keighley of the University of Copenhagen and Dr. Hilmar Malmquist of the Icelandic Museum of Natural History were able to shed light on the fate of Icelandic walruses.

Using carbon-14 analysis of walrus remains, the researchers were able to show that walruses had been present on Iceland for thousands of years and then disappeared shortly after the arrival of the new settlers in 870. The DNA samples, obtained from the bones of the archaeological finds and compared with modern walrus samples could prove that the Icelandic walruses had represented their own genetic lineage. “Our work represents one of the earliest examples of local extinction of a marine species following the arrival of humans and their overexploitation of the species. The study further contributes to the debate about the role of humans in megafauna extinctions and supports a growing body of evidence that wherever humans have emerged, the local environment and ecosystems have suffered,” explains Morten Tange Olsen, assistant professor at the GLOBE Institute at the University of Copenhagen and co-author of the of the study.

The Vikings, who had sought a new home on Iceland, dominated the ivory trade. For the material was a luxury good and was sold as far away as India. “We show in our work that even in the age of the Vikings, over 1,000 years ago, commercial hunting, economic drive and trade relations were sufficiently large to result in significant, irreversible ecological damage to the marine environment, which was exacerbated by climatic and volcanic events. The dependence on marine mammals for food and trade has been massively underestimated,” explains Xénia Keighley, lead author of the study. Although most examples of trade and human overexploitation leading to the extinction of marine species are recent, it appears that economic considerations have been placed above ecological ones in the past. Apparently not everything was better back in the good old age.

Source: University of Copenhagen