Taken as a whole, the pandemic poses many threats to wildlife around the world: conservation programs are struggling to get funding, while poachers are taking advantage of the moment because they have less to fear due to reduced patrols. However, the giants of the seas and other animals seem to benefit from the global coronavirus restrictions. Because tranquility returns to the oceans: there is much less noise from shipping traffic and the extremely loud seismic explorations have also decreased.

Some of the initially heartwarming stories about nature that thrived during the closure – such as the claim that dolphins have returned to the canals of Venice – are not true. Others, on the other hand, are true. There are signs that wild bees are benefiting from the decline in air pollution, which may disrupt their ability to smell flowers remotely. Another positive side effect of the lockdown is the drastic reduction in noise pollution in the oceans. For marine creatures, especially the whales, the tranquility should be beneficial, even for the small zooplankton.

The first cruise ship of the tourist season was scheduled to arrive at Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in Alaska on April 30. But that never happened. The cruises were canceled due to the threat of Covid-19. “There wasn’t a lot of shipping traffic, and we don’t expect one until at least the end of July,” said Christine Gabriele of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in Gustavus, Alaska. The only boats on the way are small local boats.

Gabriele is involved in a decades-long study of humpback whales in the region. A key element is the monitoring of their sounds in the midst of the underwater noise caused by heavy boat traffic. A hydrophone (an underwater microphone) anchored to the seabed at the mouth of Glacier Bay records the whales’ communication.

It is too early to make a definitive statement, but according to Gabriele it is “very quiet” regarding the boat noise. This could mean that the whales can spread over a larger area, as they can communicate with each other over much longer distances than in a noisy environment. It could also change the way they communicate. “Will they have longer periods of communication? Will they have more complex vocalizations?” asks Gabriele.

There is clear evidence that whales prefer less ship noise in their habitat. In the days following the attacks of September 11, 2001, shipping traffic around North America came to a standstill. During this time in the Bay of Fundy, Canada, Manuel Castellote and Susan Parks, scientists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, collected data for a study on the social behavior of North Atlantic Right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) and found that the noise environment had changed drastically overnight. By combining analysis of collected whale feces and underwater images, Parks and her colleagues found that ship noise is correlated with stress in whales.

“This study is pretty good evidence that industrial noise is actually a stress to marine animals,” said David Barclay, a marine acoustics scientist at Dalhousie University.

From what we know so far, the current noise environment does not seem to be too far from what the oceans sounded 150 years ago. Not exactly quiet, because non-human noises such as waves, wind, rain and even shrimp have always made a natural noise, but also not filled with man-made engine noise.

Quiet oceans are likely to produce healthier marine mammals. Free from the distraction and stress we cause, foraging would make it easier for them, mating more convenient and orientation more undisturbed.

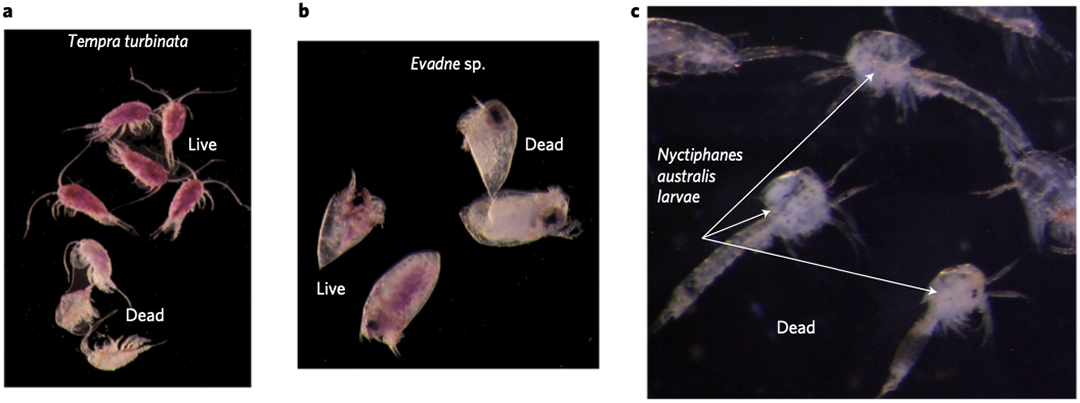

Reducing the volume could protect many more species in addition to whales. A 2017 study found that zooplankton are killed by the extremely loud bangs emitted during seismic exploration. In addition, tens of thousands of fish species have hearing abilities and many use sound for communication.

In all likelihood, the benefits of the lockdown will be short-lived for the natural environment. Michelle Fournet, a marine acoustician at Cornell University, says the “snapshot” produced right now is just that: a chance to hear what the pre-industrial world sounded like.

Christine Gabriele of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in Alaska certainly hopes the tranquility is good for the native humpback whales. Their population has been declining since 2013, many individuals are disappearing and only a few calves are born. In 2019, the numbers increased, but many of the whales remained emaciated, suggesting that they lacked food.

“If it’s a productive summer and a quiet summer, it’s going to be a real benefit for this population that’s been through some really tough times,” she says.

Source: NewScientist, The Narwhal, Rolland et al. 2012, McCauley et al. 2017