Microplastics have been detected several times in Arctic and Antarctic ecosystems. In a recent study, scientists from the University of Siena investigated whether plastic washed up on beaches finds its way into the food web of terrestrial organisms. On the Antarctic island of King George Island, they found what they were looking for: tiny soil animals had picked up microplastic fragments.

King George Island, the largest of the South Shetland Islands, is located 120 kilometers from the northernmost tip of Antarctica. It is a rough place — home to seals, penguins, a few scientific stations and not much more. Although the climate is mild compared to the mainland, temperatures in the summer months barely reach freezing, and the island is almost completely covered with ice. If microplastics can enter the food web here, then this will probably be the case everywhere on earth.

And that’s exactly what Tancredi Caruso, a professor at the School of Biology and Environmental Science at University College Dublin, and his colleagues discovered when they searched for microplastics in small organisms on King George Island. Their findings, published in the journal Biology Letters, show that microplastics become an integral part of the soil’s food web.

Microplastics are plastic parts smaller than five millimetres, though many are smaller with sizes in the micrometer range. These fragments detach from the hundreds of millions of tons of plastics produced each year and together form a huge amount of waste. And since plastic is degrading very slowly, it has accumulated dramatically in the environment – from the deepest sea trenches to the North and South Poles.

Most of the evidence of the impact of plastics on the environment comes from aquatic ecosystems, but there is growing evidence that plastic pollution is also affecting plants and soil. However, it is not yet clear to what extent plastics have actually penetrated the food webs on land — and this is where the new research by scientists comes in.

In this study, led by Caruso’s colleagues Elisa Bergami and Ilaria Corsi of the University of Siena, the researchers focused on Cryptopygus antarcticus, the Antarctic springtail. Collembola, the scientific term for springtails, are millimetre-sized animals that are very close to insects and are an important part of all soils around the world.

The specific species they analysed is essential for the food web in Antarctic soil. But it is also a good example of the numerous microscopic animals that inhabit the soils around the world. Caruso himself studied the populations of Antarctic Collembola in 2005, but had not consideredt at the time that these animals could absorb plastics, especially considering how far Antarctic soil seemed to be from sources of pollution.

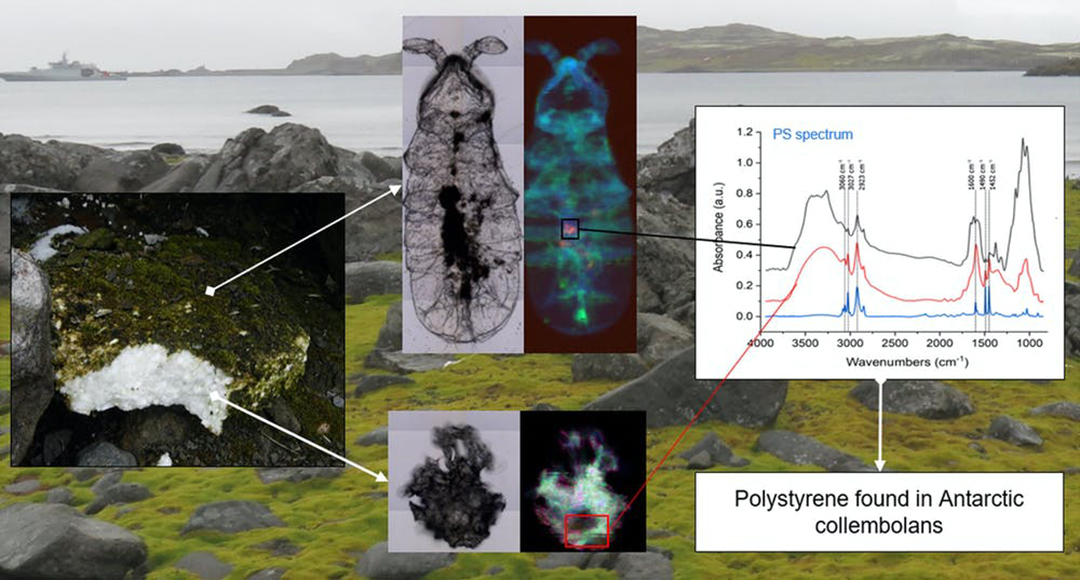

But this time Bergami took samples from King George Island. There she found animals that fed on algae, moss and lichens that grew on Styrofoam. The foam, which consisted of the same types of polystyrene that ordinary packaging is made from, lay on the beach as washed-up rubbish. The same plastic waste we find today washed up on beaches all over the world.

The researchers wanted to know if the small soil animals had absorbed polystyrene, although it is not easy to find tiny plastic fragments in the intestines of animals that can hardly be seen with the naked eye. That’s why they used infrared spectroscopy – the same technology used by forensic experts at crime scenes to split up tiny paint scrapers and return them to the original vehicle. With this new approach, they were able to make microfragments of polystyrene visible in the digestive tract of Collembola.

What are the implications? Soil animals like Collembola can be tiny, but there can be tens or hundreds of thousands of them per square meter of soil. These high numbers mean that Collembola can transport microplastic fragments over the entire length and depth of the soil and redistribute them thoroughly. Since both microplastics and small but very numerous soil animals can be found everywhere, this redistribution of plastics could be a global process.

There is still much to be done for scientists to truly understand the effects of microplastics in relation to other serious environmental impacts such as chemical pollution and climate change. But even if the springtails in the Antarctic marine zone absorb microplastics, there is a very high risk that they have already penetrated deep into the soil’s food web, possibly with negative effects on the interactions between plants and soil. In the future, scientists will have to quantify these effects and find out exactly how microplastics are interfering with global material cycles.

Source: Tancredi Caruso, University College Dublin

More on the subject: