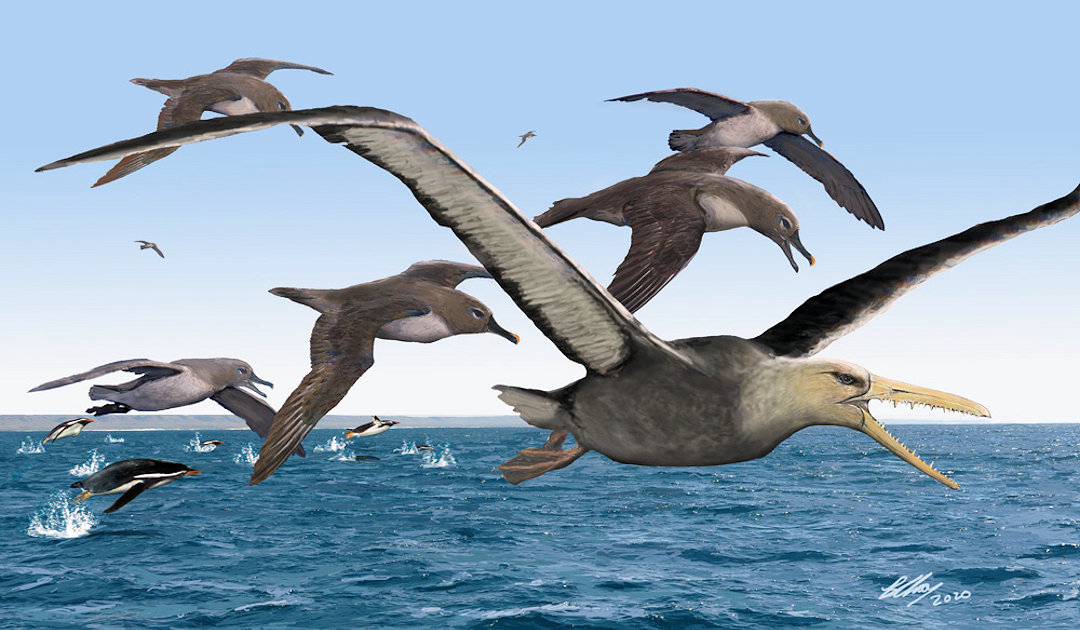

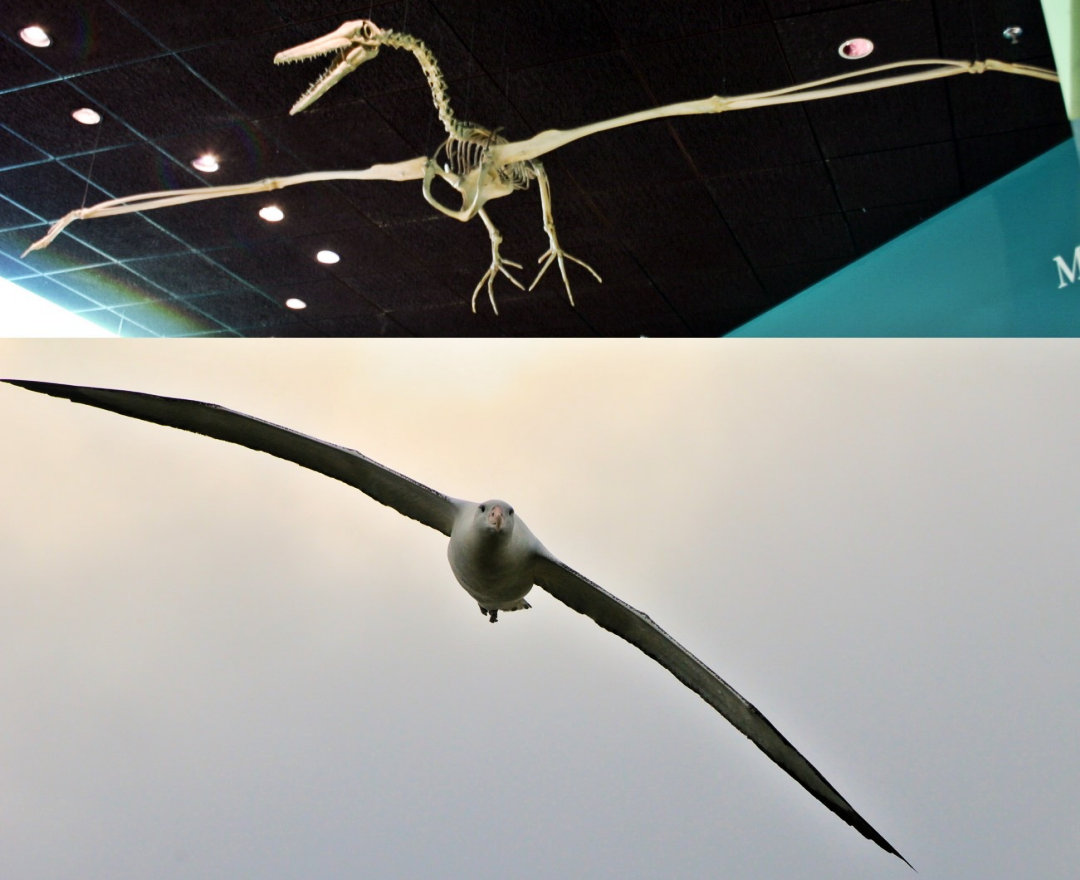

Those who travel in the Antarctic are amazed by the diverse bird life in the region. Especially one of the largest birds in the world, the Wandering albatross, impresses every visitor with its massive wingspan of 3 meters. But a surprising fossil find in a museum shows that 50 million years ago a Wandering albatross would have been just a dwarf compared to representatives of another group of birds, the Pelagornithids. According to the calculations, these birds were up to twice as large and heavy as “our” albatrosses.

“Our fossil discovery, with its estimate of a 5-to-6-meter wingspan — nearly 20 feet — shows that birds evolved to a truly gigantic size relatively quickly after the extinction of the dinosaurs and ruled over the oceans for millions of years.”

Peter Kloess, University of California Berkeley

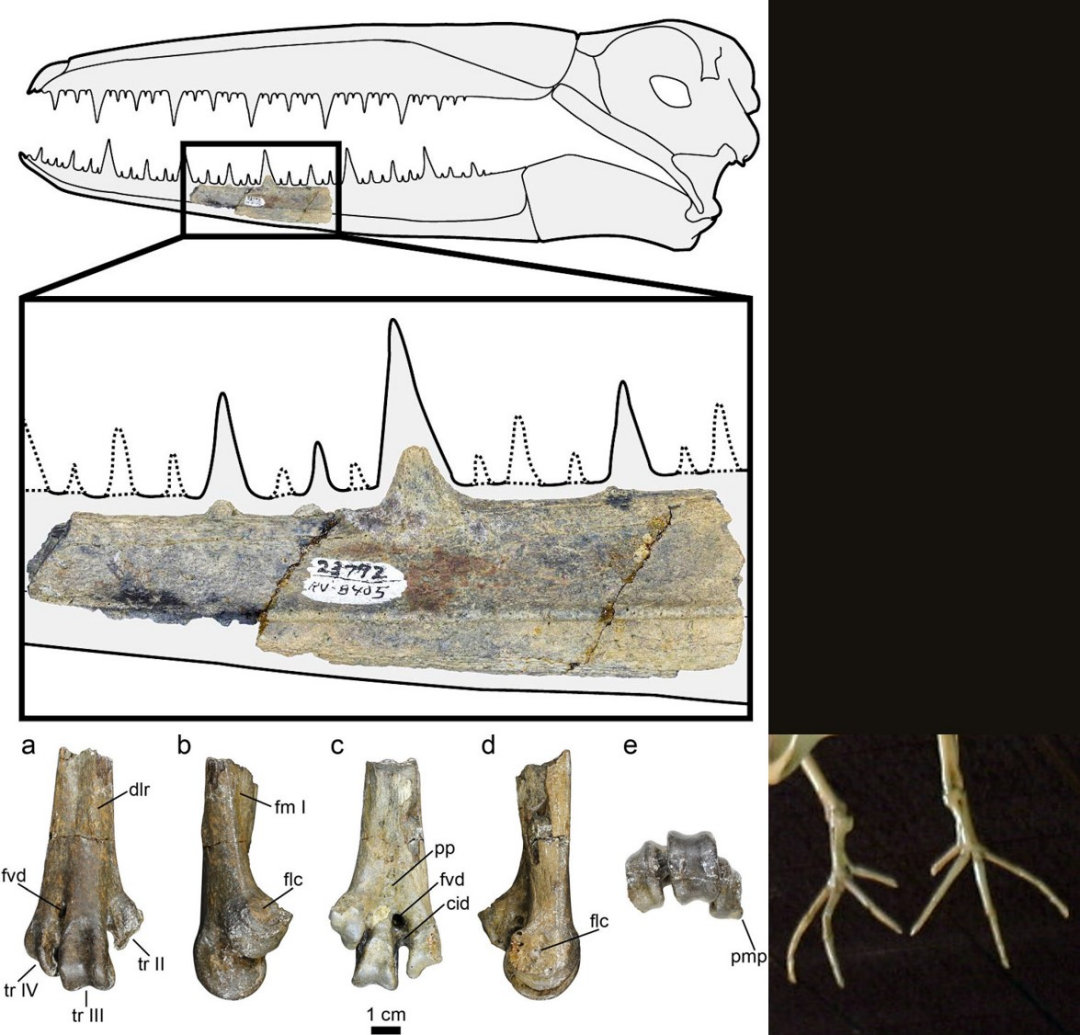

The bone finds suggest that the representatives of this family living in Antarctica had a wingspan of 5 to 6 meters. If one adds the bone structure and the comparison with the large bird species living today, these birds could have reached a weight of 20 to 40 kilograms. This makes them one of the largest known birds to date, which existed after the extinction of the flying dinosaurs about 65 million years ago. This is the conclusion reached by the lead author of the study and discoverer of the fossils, Graduate student Peter Kloess from the University of California at Berkeley. His findings were published in the journal Scientific Reports a few days ago.

The bones, which had been examined by the scientists, had been stored in the UC Berkeley Museum since the 1980s. They had been discovered on Seymour Island in the Weddell Sea, where the Argentine station Marambio is located. The island is a paradise for paleontologists and geologists as it provides a relatively easy access to layers and fossils. They had been already assigned to the Pelagornithidae as the jawbones had the characteristic bone humps. But Kloess and his co-authors had encountered a mistake in dating while further examining the foot bones and notes of the original finder. They were able to prove that the bones were not 40 million years old, as originally thought, but 10 million years older than the jaw fragment. This also proved that the Pelagornithides had already lived together with the first penguin species in a then even warmer Antarctica. In addition, the birds were already giants in the sky at that time, most likely the largest of their family.

When asked how these giant birds probably lived at a time when Antarctica was even warmer and greener, the researchers point to the parallels with today’s albatrosses. They use the winds around Antarctica as a propulsion aid for long sailing and thus save energy on their long foraging trips. Experts for the Pelagornithids can imagine a similar system. It is also probable that the birds did hunting fish and squid at that time. The pseudo-teeth, which were actually only bone humps covered with keratin and had been about 3 centimeters in length, were ideal for holding agile and slippery prey. Co-author Thomas Stidham of the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoenvironment commented: “The big ones are nearly twice the size of albatrosses, and these bony-toothed birds would have been formidable predators that evolved to be at the top of their ecosystem.” The Pelagornithiden bird family was not only native to Antarctica, but worldwide and disappeared about 2.5 million years ago. But for at least 49 million years they dominated the skies on their mighty wings. Would they have a similar fascination with their size today as the albatross?

Dr Michael Wenger, PolarJournal

Link to the study: Kloess et al( 2020) Sci Rep 10 Earliest fossils of giant-sized bony-toothed birds from the Eocene of Seymour Island Antarctica; doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75248-6

More on the subject: