The region around the Antarctic Peninsula was not previously known for exceptionally high seismic activity. But since the end of August this year, researchers at the University of Chile have used automatic detection techniques to record more than 30,000 earthquakes in the Bransfield Strait, which is located between the South Shetland Islands and the Antarctic Peninsula. More detailed studies could reveal an even larger number. The greatest activity was seen mostly in September, with more than one thousand quakes per day. By November, the number of daily earthquakes decreased significantly.

Several tectonic plates and microplates meet in the region around the Bransfield Strait, which are in motion and therefore trigger tremors more frequently. However, scientists at the

The tremors were recorded and localized, among others, by the seismological stations on the surrounding research stations: by JUBA and ESPZ on the Argentine stations Carlini (formerly Jubany) on King George Island and Esperanza on the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, respectively, and by PSMA on the American Palmer Station on Anvers Island.

CSN geophysicist María Constanza Flores identified the more than 30,000 quakes while analyzing the JUBA station records using a special method based on automatic signal detection using cross-correlation and detectors for changes in signal amplitude at different time intervals. This made it possible to analyze a large amount of data recorded at a small number of stations. For example, the analysis showed that the sequence began with a barely perceptible earthquake on August 28.

The South Shetland Islands separate from the Antarctic Peninsula

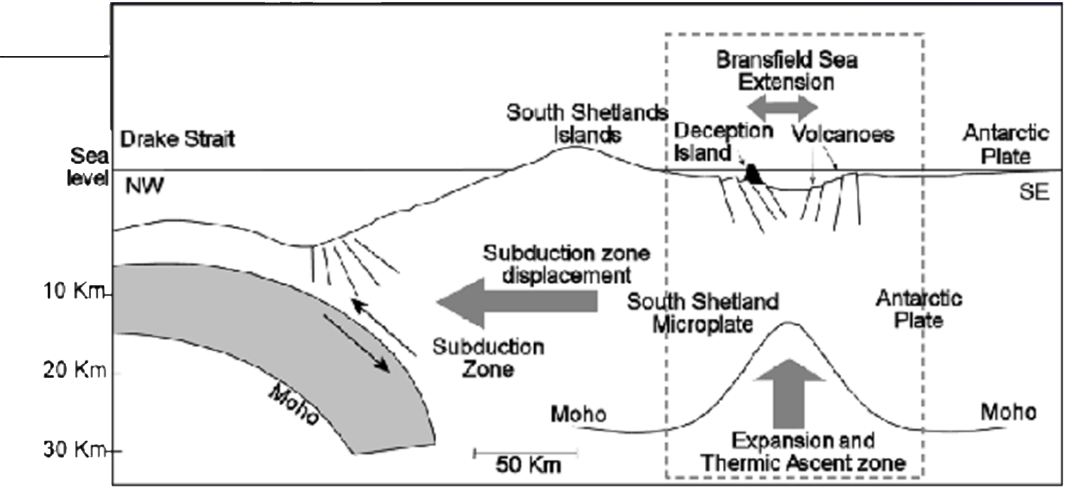

The tectonics around the Antarctic Peninsula is very complex – there are various processes of convergence, divergence and lateral displacement of major and minor plates as well as plate segments in a relatively small area. And for the South Shetland Islands, these numerous quakes are not without consequences. The South Shetland microplate and the Antarctic plate have been moving apart much faster than before since the increased activity. Previously, the islands drifted away from the peninsula at a rate of seven to eight millimeters per year; now it’s 15 centimeters per year. “It’s a 20-fold increase … which suggests that right this minute … the Shetland Islands are separating more quickly from the Antarctic Peninsula,” says Sergio Barrientos, director of the National Seismological Center.

The Antarctic Peninsula is one of the fastest warming places in the world. But according to climate scientist Raul Cordero of the University of Santiago, it is not yet clear what impact the quakes might have on the ice in the region. “There is no evidence that this kind of seismic activity … has significant effects on the stability of polar ice caps”, Cordero said.

Julia Hager, PolarJournal