January 2021 marked the 108th anniversary of the death of Dr. Xavier Mertz. He was the first Swiss to set foot to Antarctica. The crew member of the expedition of 1911-1914 under the expedition leader Douglas Mawson met a bad end in the eternal ice. A reconstruction based on his diary.

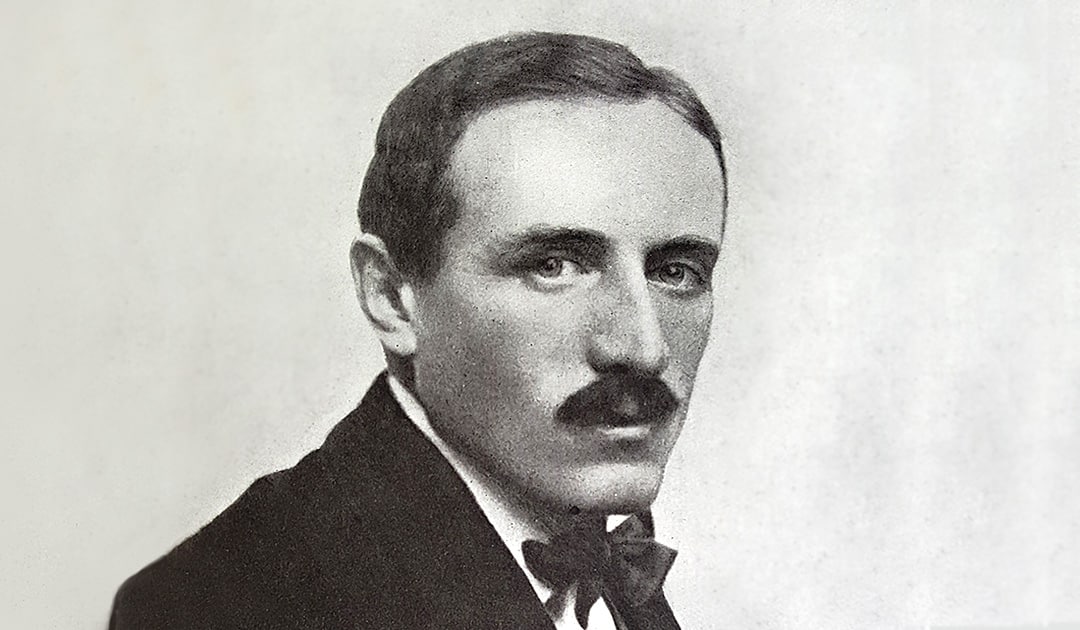

“You can clearly see how good fortune and bad fortune are not far apart. Such is the course of the world,” Xavier Mertz noted in his diary on November 4, 1911, as he described how his comrades in the icy desert received mail with good and bad news. How right he was: 14 months later, Xavier Mertz was dead. Caught up in the aftermath of a misfortune that was basically accidental, and poisoned by the flesh of the dogs he was responsible for. When everything had gone so well as to perfection. But let’s start from the beginning with the story of the first Swiss to ever set foot to Antarctica. Xavier was born in 1883, one of six children of the Mertz family of entrepreneurs in Basel. His father Emil had made it prosperous as the owner of a large air conditioning factory.

He himself studied philosophy, geology and jurisprudence in Basel, and was

an outstanding alpinist and skier: as a competitive athlete, Xavier made the headlines in the newspapers time and again. He was also an avid photographer.

Today, it is not known exactly what motivated him to sign up for an Antarctic expedition: in 1910, he applied in writing to the Australian geologist Douglas Mawson for his planned state Antarctic expedition: from the station on the coast of Adelie Land, he was to spend two years mapping around 2,400 kilometres of coastline of that part of the Arctic that lay directly opposite Australia. He was also to set up the first radio network on the southern continent and research how the magnetism of Antarctica could be used for aviation. The first overflight of the South Pole was also planned, but the plane suffered a crash landing a few weeks before the start of the expedition.

Douglas Mawson rejected the application from Basel. But Mertz did not let up and traveled to London without further ado when Mawson was there and introduced himself to him personally. Mawson obviously took a liking to the committed and top-fit mountaineer and accepted him into the team: The first Swiss to set foot on Antarctica was now a member of the first Australian Antarctic mission. Among other things, he should be responsible for the 48 Greenlandic sled dogs. One of the dogs he named Bethli, another he named Basilisk after his hometown.

At midnight from July 27 to 28, 1911, the expedition ship “Aurora” set sail from London for Tasmania and from there on to Adelie Land. “For two or three years it went out into the world!” wrote Mertz confidently in his diary.

On January 18, 1912, the “Aurora” dropped 18 men off on the coast of Adelie Land at Cape Denison and with them the dogs, 5200 cases of equipment, 18,000 gallons of gasoline, 5900 gallons of kerosene, lumber, telegraph poles, and tons of provisions. A second research station was set up by another eight men about 600 kilometers west of the base. The ship was to pick up the men again in mid-March 1913. Xavier Mertz was assigned to the main group.

In the windiest place on earth

What the men could not have known: they were building their station in one of the windiest places in the world! Here the ice winds from the interior of the continent meet and flow out into the open sea. The average wind speed on Cape Denison throughout the year is 70 kilometres per hour, which corresponds to wind force 8.

Wind storms of 160 kilometres per hour for days on end and the corresponding driving snow are not uncommon. The record measured by the expedition was a staggering 320 kilometres per hour.

Xavier Mertz noted in his diary on 26 April how dramatically such weather conditions affected the researchers’ work: “The observation station is ten metres from the hut. Correl (one of the crew members, editor’s note), on his way there, was knocked down by the wind two meters next to the hut, lost direction and, seeing nothing but snow, wandered all around the hut. He landed on the coal pile at last, and after a struggle of three-quarters of an hour found his way.” Those are tough conditions for 14- to 16-hour workdays in sub-zero temperatures.

Nevertheless, Mertz likes it at Cape Denison, for on another day he noted: “The explorer’s impulse to see new and unknown things animates each of us. We are on ground that has never been trodden by man. I yodel out of joy into the stillness of the evening and dance over the slippery snow.”

Again and again, groups undertake days and weeks-long exploratory trips on dog sleds into the interior and along the coast.

Fan out in teams

The largest of these expeditions started on November 10, 1911: six groups set off simultaneously in different directions. The longest and most arduous of the planned journeys to the vicinity of the magnetic South Pole had been decided by expedition leader Mawson for himself. As his companions he chose the two most capable men: The English lieutenant Belgrave Edward Ninnis and Xavier Mertz. “For our farewell breakfast we enjoyed fine penguin egg omelets,” the latter wrote in his diary.

The journey is arduous. Again and again, the three of them are pinned down by storms that last for days.

“We had to stop because three dogs had fallen into crevasses” (November 20).

“After lunch Ninnis fell into a crevasse two feet in front of our tent. It was only when we looked through the hole into the depths that we realized that our camp was in the middle of a

crevasse. We saved Ninnis” (November 21).

“Unpleasant light, so that one could not distinguish the ground formations before one’s feet. Twelve and a half miles daily performance” (November 26).

“Down below, we miss Bethli” (Nov. 26).

“Bethli no longer appeared” (November 28).

“Nine miles was the day’s effort. Quite respectable, as the surface was at times exasperating. The sleds toppled over and over, had to be straightened up again and again, pushed upwards. I almost broke my right forearm when the heavy sled tumbled over me once. The dogs do their best, but often their strength is not enough” (December 2).

“Drift, wind, wind, drift (blizzard, editor’s note). All we can do is lie in our sleeping bags all day” (December 6).

“Wind, Drift, Drift, Wind” (Dec. 7).

And finally, on December 14: “We have now been 31 days on the road and have come 270 miles” (December 11). That’s about 430 kilometers.

Ninnis breaks in

On December 14, the tragedy begins. As the last in the column of three, Belgrave Ninnis falls, unnoticed by the other two, into a crevasse with his sled and dogs, “as we had passed hundreds the last weeks”. “A hundred and fifty feet down we spied the back of Ninnis’s sled in a crevice. A low dog whine penetrated to the surface, where we lay, listening and consulting. No other sound was to be heard.” Mertz suspects that Ninnis’ sled collapsed in the rear and Ninnis was struck dead by the sled falling on him. “We waited hours and hours,” the dog whine died away, Ninnis was dead. Making matters worse was the loss of material: “It was only late that we realized that almost all our food, tents, picks, shovels had gone into the crevasse with the sled and the dogs.”

With the few remnants of their equipment and provisions stowed on the other two sledges, Mawson and Mertz immediately set out to return to the station. They know it’s going to be a race against death.

For days they march back, pinned down by snow and wind storms, marching all night in good weather. From their jackets they build makeshift tents for sleeping and sails for the sledges. Food is more than scarce. The dogs are exhausted, one by one they are going limp.

December 17: “Mawson could hardly sleep for pain. Snow blindness.”

On the same day they shoot the first dog and feed it to the other dogs.

December 18: “We’re eating dog meat now, it’s better than nothing. Of the last three dogs, only Ginger pulled, so Mawson and I had to work hard to get the sled moving.”

December 23: “Six o’clock in the morning. Five and a quarter miles. We have now travelled 115 miles since the scene of the accident where we lost Ninnis.” That’s 184 kilometers in 9 days. 250 kilometres still lay ahead of them.

December 24: “We must travel faster if our provisions are to last. From Pavlova’s legs we cooked a soup.”

Dec 26: “Quite cold, so fingers remain constantly stiff even in felt and fur gloves.”

December 27: “This drift is uncomfortable because everything just slowly gets wet. When I lie in my sleeping bag at night, I notice how one piece of clothing after the other gradually thaws slowly on my body. You can’t exactly call such conditions comfortable.”

January 1, 1913: “New Year! No travel weather. Light incredibly bad, sky cloudy, so we did not get far. The dog meat does not seem to go well with me, for yesterday I was a little nauseous.”

Exhausted to death

These are the last words Mertz writes down in his diary. Mawson later wrote in his book about this expedition that Mertz admitted to severe pains in his abdomen “only when I asked him emphatically.” “It was clear that his condition was more precarious than he meant.”

This day and two more Mertz is unable to march on. Valuable time goes by unused. On January 6, the two set out again, but after only a few miles, Mertz is so weak that Mawson puts him on the sled and pulls him. From the cold, the skin of both begins to separate from the body.

On January 7, Mertz is so weak that Mawson has to help him into his sleeping bag. Mertz has fits, he shakes and talks deliriously, finally falls silent. That same night, he dies.

For many years, it was later suspected that Xavier Mertz died of vitamin A poisoning from eating dog liver. But today it is assumed that he died because he ate meat at all and so much at once. Because Xavier Mertz was a vegetarian. His digestion could not cope with the amount of meat he suddenly ate – especially as he was already very weakened. The emaciation, the unfamiliar, hard-to-digest food, and the extreme physical exertion in biting cold were a lethal combination for Mertz. Douglas Mawson used Xavier’s skis to build his grave in the eternal ice.

The last survivor was now still 160 kilometers away from the rescuing station. With almost superhuman effort, Mawson fought his way forward kilometre by kilometre, falling several times into crevasses from which he was able to free himself again, the skin of his feet peeling off, his hair falling out in clumps, for days he was caught in a snowstorm, his provisions running out. Mawson would have died of exhaustion and hunger had he not discovered a huge snowman on January 29th, with a sackful of food deposited on its head: the men of the station, by now all returned safely from their expeditions, had built this depot in search of Mawson, Mertz, and Ninnis. The last 37 kilometers were now still doable.

Mawson can save himself

On February 8th in the afternoon he finally reached the station on Cape Denison and saw just on the horizon the ship disappear, which had picked up the crew as planned…

But fortunately for Mawson, five men remained at the station to search for the three missing men. Although the rescuers were able to radio to the ship that it should return immediately – on the very radio network that Mawson’s crew had set up earlier. But because of the bad weather it was not possible for the “Aurora” to sail to the coast again. Mawson and his five rescuers had to wait almost a year for the next ship. Small or big detail on the side: On December 14, 1911, i.e. during the time when Mawson, Ninnis and Mertz were on their expedition, Roald Amundsen was the first person to reach the South Pole.

“A character”

“We loved him,” Mawson later wrote of Xavier Mertz in his book The Home of the Blizzard, “he was a character – magnanimous and distinguished.” Mawson named the first major glacier Mawson crossed after Mertz’s death after his Swiss companion – the Mertz Glacier. The 40-kilometre-wide, 160-kilometre-long glacier, whose tongue juts far out into the sea, made global headlines in 2010 because it was rammed by a giant floating slab of ice, causing its tongue, which juts out into the sea, to break away. In 1914, Douglas Mawson traveled to Europe and also visited the Mertz family to offer his condolences on the loss of their son. In his luggage he probably also had the diary and the photographs. It was not until the late 1960s that Xavier’s estate reappeared. An eight-part report on Mertz appeared in the “Beobachter” in 1969/70. The responsible editor delivered more than 100 pictures from the Mertz estate to the State Archives of Basel-Stadt, where they are still to be found today.

Author: Christian Hug

Images: Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW

Interesting reading! Thanks 🙏

Very interesting, thank you !!