Whalebone, baleen, walrus tusk, plastic line, H22 x B11 x D9cm

Idris Moss-Davies, Qikiqtarjuaq (Broughton Island), Nunavut, Canada

April is over. It has been the coldest April for many years as well. But May is not yet a happy month either. The temperatures are only rising slowly, the trees are hesitantly turning green. At least the days are reliably getting longer and longer. Numerous migratory birds are now returning to the north. To us, however, earlier than to the Canadian Arctic. Nevertheless, the vast territory of Nunavut in northern Canada, with around 150 breeding and nearly 300 bird species that have been sighted, has an impressive biodiversity. (Richards / Gaston: Birds of Nunavut, 2018).

Whalebone, walrus tusk, cord, H15 x B29 x D6 cm

Emily Illuitok, Kugaaruk, Nunavut, Canada

Even hummingbirds (more specifically, the rufous hummingbird) can be found in southern Alaska during the summer. Most of them are migratory birds, which from the end of April migrate in large numbers to the north of the territory and breed there. And they are a welcome addition to the diet of humans and numerous animals. In addition to hunting the birds, their eggs are also collected. (Fig. 1 Egg collector, Idris Moss-Davies) The rest of the bird is also used, not just the meat. Among other things, clothes and blankets are made from the plumage. Both from the down plumage of young animals and the plumage of adult birds.

Steatit, H15 x W16 x D15cm

K. Kumak, Aklulivik, Nunavik, Canada

The lack of trees forces the birds to breed on the ground or in the cliffs. Both pose dangers for eggs and chicks. And the adult birds develop strategies to protect their brood. But breeding on the cliffs does not protect against predators. Polar bears keep climbing into the rock to get to the coveted eggs. That people also dare to go there is shown by a sculpture made of whale bones and walrus tusks by Emily Illuitok from Kugaaruk (Nunavut, Canada), which depicts two Inuit collecting eggs from seabirds on a cliff. (Fig. 2) The structure of the porous whale bone is ideal for depicting the rugged cliffs. In art, above all, one’s own environment is represented.

Muskox horn, H23 x W20 x D22cm

K. Nutik, Ulukhaktok Northwest Territories, Canada

Art depicts the own environment. With the materials that this environment provides. A bird at its nest by Mary Kiinalik Kumak from Salluit is carved from the gray soapstone so typical of Nunavik (Arctic Quebec). (Fig. 3) The muskox horn is more flexible than stone. It can be heated and thereby made malleable. However, the range of these animals is limited and artists who use the horn are mostly found in Ulukhaktok on Victoria Island. The island belongs partly to Nunavut and partly to the Northwest Territories. Caribou can also be found in the area. A crane (Fig. 4) was created from the horn of the musk ox.

Muskox horn, H57 x W54 x D24cm

Adam Ekpakohak, Ulukhaktok Northwest Territories, Canada

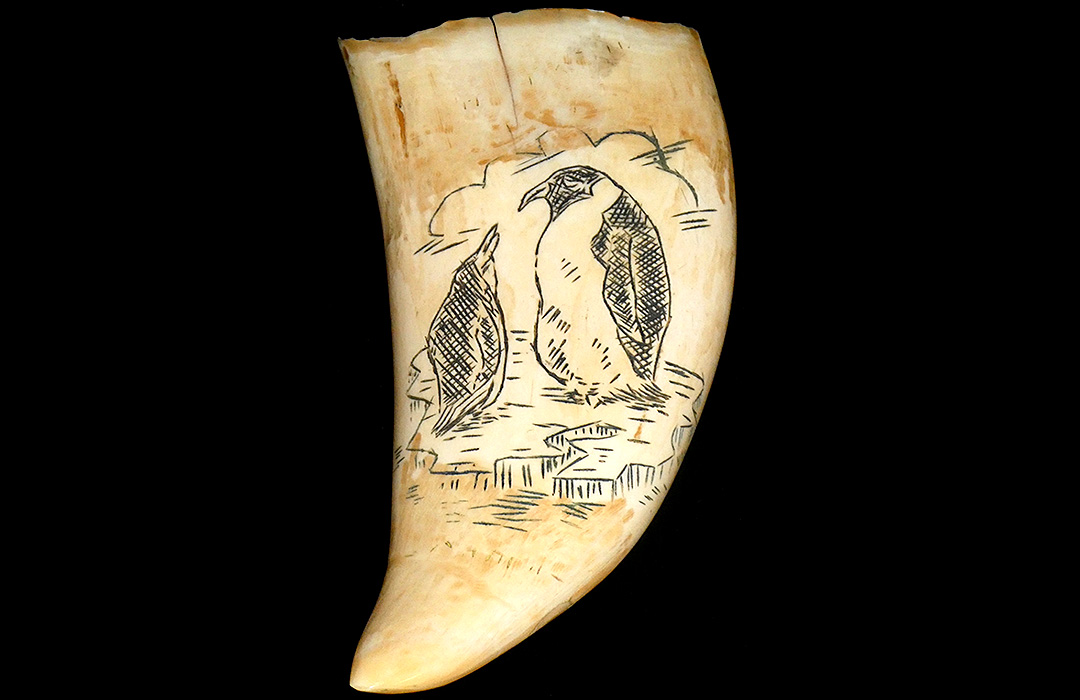

Another (Fig. 5) stands on a base made of caribou antlers. And there, in the flat plains of the island, the cranes depicted breed. One outlier in the collections of the Museum Cerny is a pot dial tooth. (Fig. 6) To this day, commercial whale hunting is practiced from various locations in parts of the world. In the Arctic, this hunt is strictly regulated and the Inuit can only hunt a certain number of whales per year, which is reset every 5 years. The teeth of the sperm whale are made of ivory and, decorated with carvings, were a popular souvenir as early as the 19th century. In East Greenland, tupilaks (spirit beings) are still made from whale tooth, among other things. The tooth shown here from the first half of the 20th century shows two penguins – parent bird and young bird – which, as is well known, are found in Antarctica. The animals do not occur in the Arctic.

Pot whale tooth, colour, H14 x W6 x D4cm, unknown

The range of materials used is as surprising as the number of bird species in the Canadian Arctic. We’ll look at some of these materials in more detail in upcoming articles.

Martin Schultz, Museum Cerny / Translation by Martha Cerny