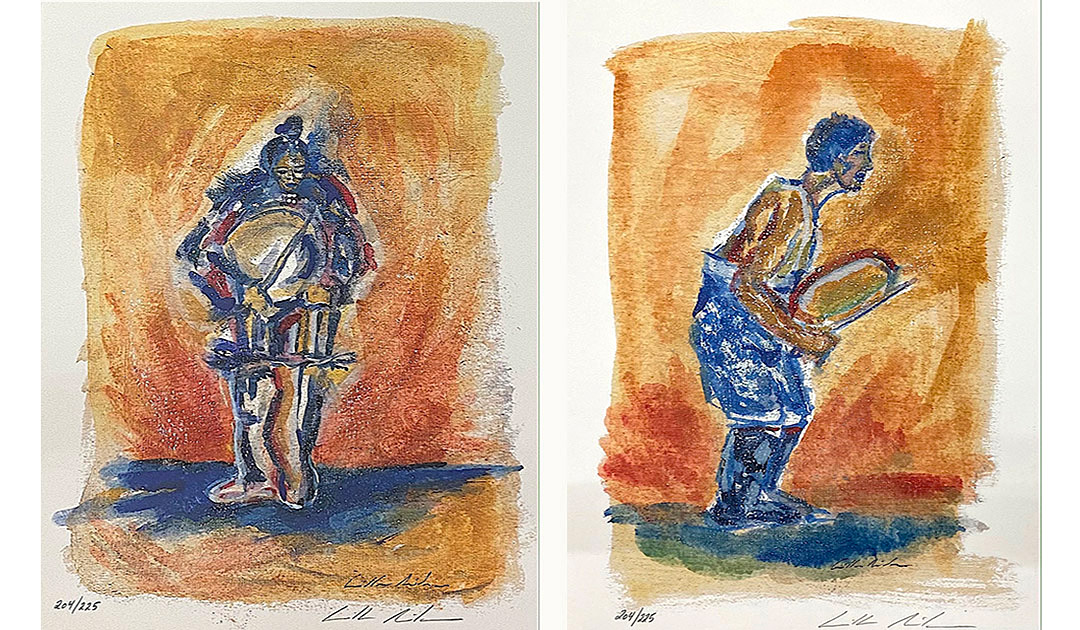

Figure 2 (right) Male Drummer, ca. 2005, 204/225, Paper, ink, H42 x W35 cm, Lithograph

Camilla Nielsen, Nuuk Greenland

Peoples of the Arctic use a wide range of materials in their art. Many of these can be found locally and have always been used, such as stone, horn, antlers, baleen, ivory and wood. Although not all materials are equally readily available, for example, on Baffin Island, due to the lack of trees, hardly any works of art are made from wood. In the 1950s a new tradition was established in northern Canada that quickly spread to the North American Arctic and enjoyed worldwide popularity – that of printing. The collection of Museum Cerny has ca. 350 works on paper.

Already in the 19th century paper, which was brought to the Arctic by travelers and settlers, was being used extensively. Very early examples of this originate in Greenland. Aron von Kangeq (1822-1869) was one of the first Greenlanders to have produced a comprehensive body of paintings and prints. Kangeq became known to his contemporaries as the illustrator of the first Greenlandic newspaper Atuagagdliutit, which appeared from 1861, was free for Greenlanders and aimed to bring Danish culture closer to the Inuit.

By 1900 a thriving tourist industry had developed in West Greenland. Similar to those by travelers and settlers from Europe, the drawings of the Inuit mainly contain depictions of people and the landscape. In addition, however, religious and mythological depictions and, above all, hunting depictions were also popular with the mostly European buyers. Last year the National Museum in Zurich exhibited drawings by Jakob Danielsen in the exhibition “Greenland 1912”, which had been acquired during the expedition lead by Alfred de Quervain and brought back to Switzerland. Contemporary art from Greenland was largely unknown in Central Europe then as now. In contrast to the figures called Tupilak, mainly made of whale tooth, narwhale tooth, walrus tooth or wood, graphic art has rarely found widespread use here to this day. However, a printing tradition established itself in Greenland in the 1960s and 1970s – around 10 years later than in Northern Canada. (Fig. 1 & 2) Female and Male Drummers, limited edition by the Danish artist, Camilla Nielsen.

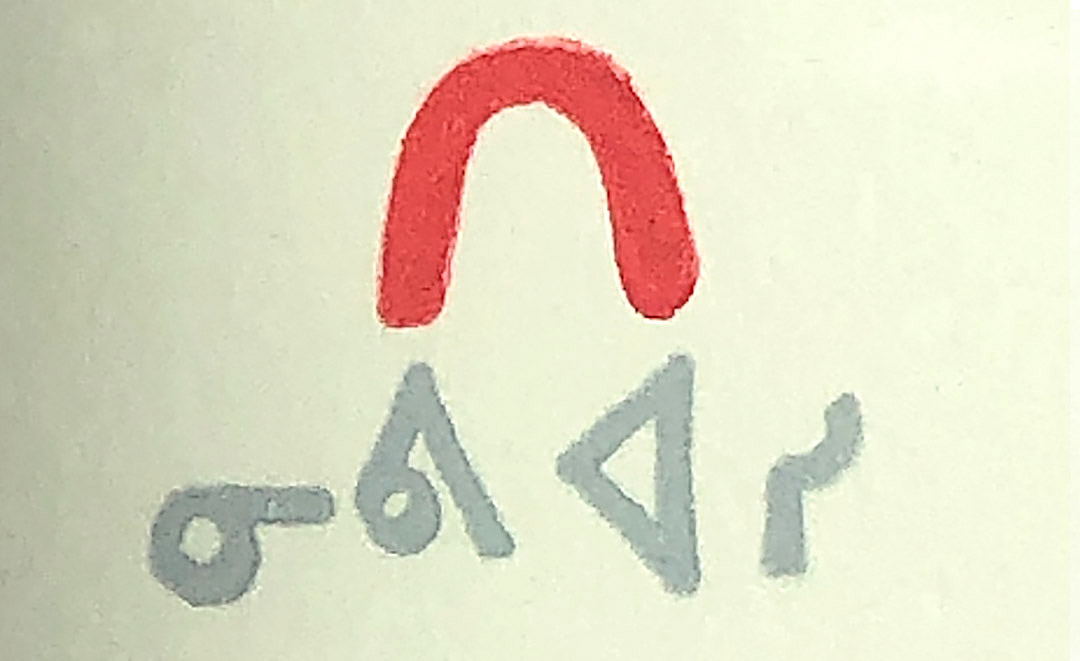

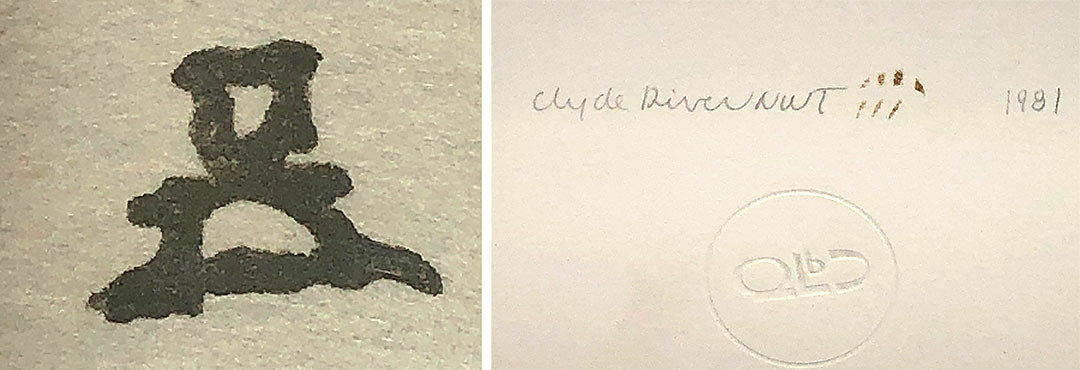

In the 1950s in Kinngait (formerly Cape Dorset), Nunavut, experiments were carried out first with textiles and later with paper. Printed textiles from the Canadian Arctic can currently be seen in the exhibition “ᖃᓪᓗᓈᖅᑕᐃᑦ ᓯᑯᓯᓛᕐᒥᑦ Printed Textiles from Kinngait Studios” at the Textile Museum of Canada. In 1960 the first series of limited prints was published in Kinngait. Inuit artists elsewhere quickly followed and printing studios were set up in Pangnirtung, Puvirnituq, Qaminittuaq (formerly Baker Lake) and Ulukhaktok (formerly Holman). The Canadian artist James Houston (1921-2005), who had travelled to Japan in 1958 to learn the Japanese printing techniques, was in charge of this project. The influence of Japanese printing can be seen, among other things, in the use of mulberry paper and a stamped “chop” for the workshops, as well as others for the artists and printers. The “chops” differ according to location and identify the respective prints that were approved for the series of the year. In addition, the seal of the Canadian Eskimo Arts Council can be found on the paper, which was initially stamped and later embossed. (Fig. 3, 4, 5, 6, & 7) The prints from all workshops are numbered (as part of a series of mostly 30 or 50 copies per motif), dated and signed, and some also have the title of the picture and the name of the printer. Either in the Inuktut or Latin letters.

Johnniebo Kinngait, Nunavut, Canada

Joe Tarilunili, Puvirnituq, Nunavik, Canada

The motifs, as well as the materials and printing techniques, have constantly changed and expanded over the past 60 years. Mythology (Fig. 8), wildlife (Fig. 9) and domestic scenes, for example, have been supplemented with technical changes and depictions of climate change.

Individual artists have also achieved great international recognition and are highly valued on the art market. A copy of the print “Enchanted Owl” by the artist Kenojuak Ashevak (1927-2013) from 1960 was auctioned in 2018 for 216,000 Canadian dollars. However, artists do not benefit from such prices on the art market.

Kenojuak Ashevak, Kinngait, Nunavut, Canada

Kenojuak Ashevak supported a project with the proceeds from the sale of one of her prints (Fig. 10) in 2004 to set up a printing workshop in Uelen in Northeast Siberia. So far the effort has been unsuccessful and only 20 prints made in 2004 were produced. Books have been written about the printing practices of the Inuit. So covering the subject exhaustively in this article is not possible, rather only a brief overview. The library of the Museum Cerny offers extensive literature on this topic and can be used during the regular opening times by prior arrangement.

Martin Schultz, Museum Cerny / Translation by Martha Cerny