What are the benefits of the Polar Expeditions Classification Scheme (PECS)?

In order to offer a structured orientation aid for serious presentations and comparisons and to make the achievements of modern polar expeditions better understandable, comprehensible and comparable, an international team around the initiator Eric Philips (AUS) with Steve Jones (UK), Damien Gildea (AUS), Michael Charavin (F) and Christoph Höbenreich (A) has worked intensively to create a scheme of principles and to systematize definitions.

The elaborated Polar Expeditions Classification Scheme (PECS) allows for a contemporary characterization of polar travel by combining traditional and modern terminology into one label. It includes a non-judgemental classification system with definitions of commonly used terms based on modern travel disciplines as well as polar geography.

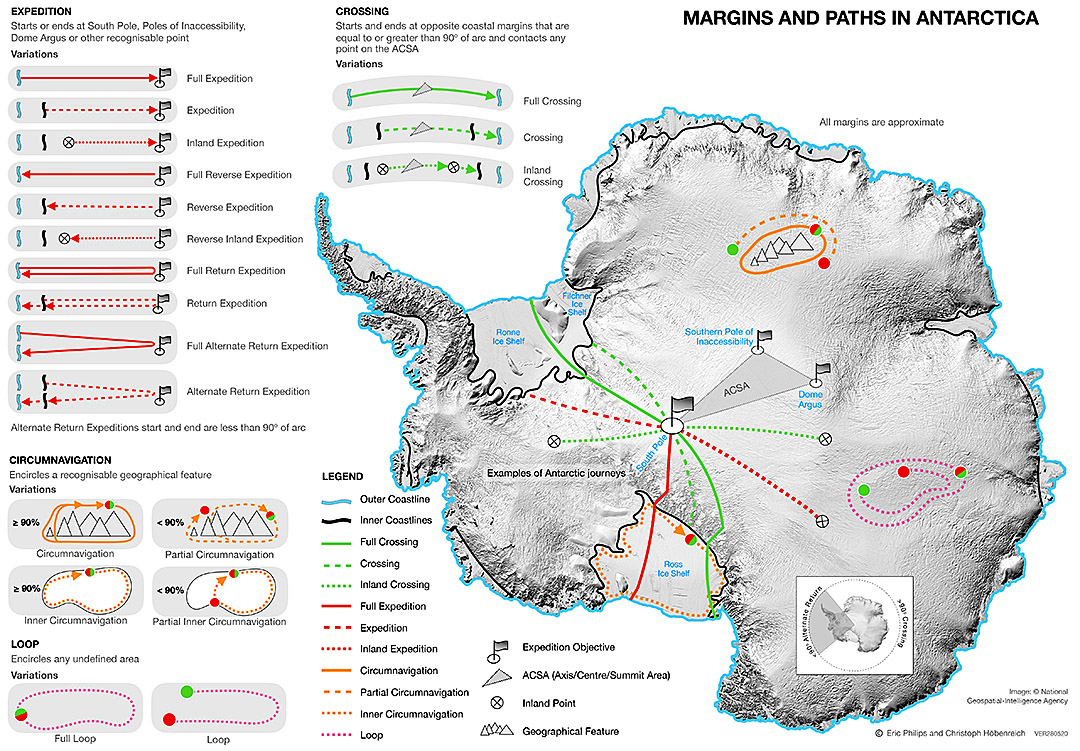

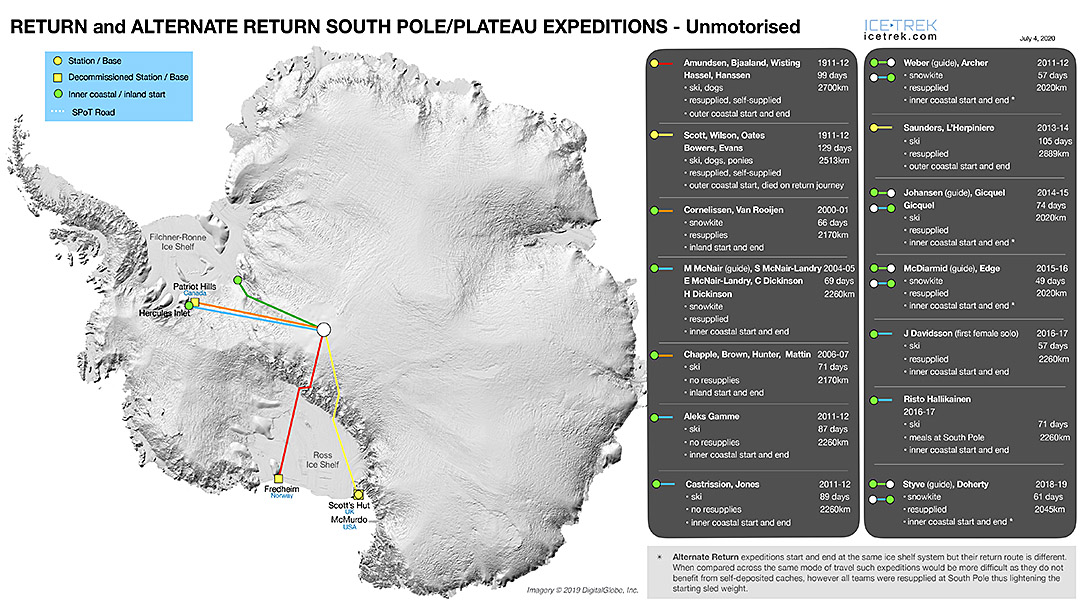

PECS applies to extended, non-motorised polar voyages conducted primarily on snow and ice, both on land and on water, in Antarctica, Greenland and the Arctic Ocean in the form of crossings, circumnavigations or loops. It can also be applied to ice travel in non-polar regions, such as Patagonia, Lake Baikal, Alaska, etc. Relevant geographic features, modes of travel, margins, routes and directions, and support are systematically defined to help polar travellers classify their journeys. Together with the clear designation of the exercised discipline (“Ski expedition”, “Snowkite expedition”, “Bicycle expedition” etc.) a differentiation of the sports and an objective comparison of the performed performances becomes possible. For example, journeys which are not completed in one piece but in sections spread over several periods of time and which, taken together, lead to a greater overall performance, cannot claim the greater overall performance as a whole, but rather “only” a composition of their partial sections.

In this way, PECS creates a framework that takes into account past performance with historical and geographical understanding and allows for a more objective assessment of new performance. The Guinness Book of Records, which analyses and collects world records of all kinds according to the criteria of measurability, comparability, standardisability and breakability, has expressed interest in PECS as a tool for assessing achievements made.

Even if it remains to be seen whether and how this systematisation and generalisation of the colourful variety of modern polar expeditions by PECS will prove successful, it is a first step towards a comprehensive and well-founded orientation aid. Or, as one critical mind put it in a nutshell: “It is complicated. But it is the most compact simplification of the complication”.

The core elements of PECS are briefly summarised as follows

Number of participants (team size)

Team

More than one person during all or part of a trip.

Solo

A single person travels alone for the entire length and duration of a trip. If not explicitly stated solo, a team is assumed. Soloists should only lead temporary encounters with others.

Travel mode (Mode of travel)

The travel mode is the discipline by which a trip is predominantly conducted to get around and transport one’s gear, usually by pulling a sled. “Manhauling” is a traditional term for a mode of travel in which supplies and equipment are carried on a sled (pulka), usually by ski, but also by foot or snowshoe, in any case entirely under one’s own power. The sometimes used terms “unassisted” or “unmotorized” to emphasize that no wind energy, dogs or machines are used for propulsion, are no longer necessary today, because the main categories and disciplines of sportive locomotion on polar journeys are simple, clear and self-explanatory. Combinations are also possible.

Margins Antarctica, start and end points

The starting and ending points of a journey are usually determined by geography and usually have a historical context.

Outer/Seaward Coastline

The outer coastline is bounded by sea or annual sea ice and includes the ice shelf (commonly used in early expeditions, but rarely used today).

Inner/Landward Coastline

The inner shoreline lies at the landward beginning of the ice shelf in the area of the grounding line/zone. Here, the ice sheet flowing from the mainland separates from the bedrock and drifts up to the sea, where it forms the shallow and up to a thousand metres thick ice shelves. The transition is usually difficult to detect in nature and to delimit by satellite remote sensing.

Inland Point

An inland point is a point located landward of an inner coastline.

Full

A voyage using the outer coastline is considered “complete”. A Full South Pole Expedition starts at an outer coastline. A Full Antarctic Crossing begins and ends at opposite outer coastlines.

Pathways

Paths characterize the direction and route of a journey from start to end point. The geographical feature as the object or destination of the journey must be included in each case.

Geographical Feature

A geographical feature is a recognisable landform that can be reached, circumnavigated, traversed or climbed as a defined destination of a polar voyage, e.g. ice cap, mountain, island, lake, archipelago, continent, etc.

Crossing

A traverse traverses a geographical feature (for example, the continent of Antarctica), begins and ends at opposite points or edges, and proceeds in a straight line or in an arc of at least 90°.

double crossing

Double crossing there and back. Often done in Greenland.

Expedition

A term generally used to describe a journey that is of a discovery or exploration nature or that leads to remote or unexplored areas. For polar travel also a general term for a route that is neither a crossing (crossing) nor a circumnavigation (circumnavigation) nor a loop (loop).

Return Expedition

An out & back expedition to a significant destination, starting and ending at the same point.

Alternate Return Expedition Starts and ends at different points, takes a different route to a significant destination than back, and describes an arc of no more than 90° (differentiation from crossing).

Reverse Expedition

A reverse expedition starts at a significant usual destination point (for example, the South Pole) and ends at a usual starting point (for example, coastline).

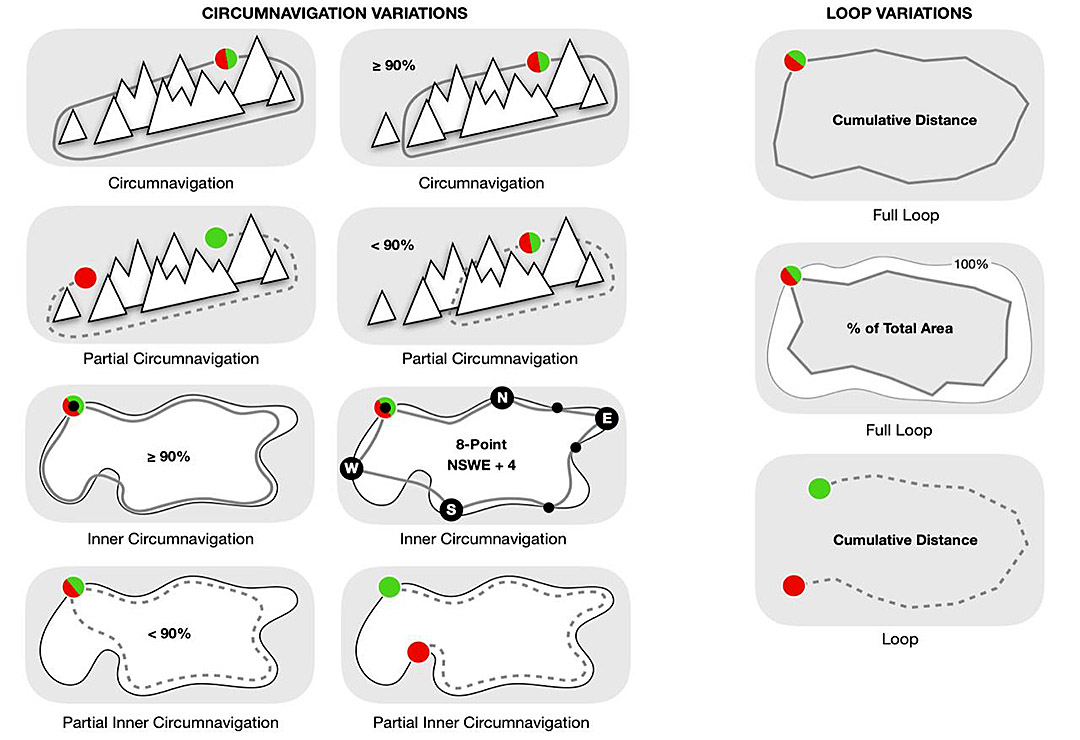

Circumnavigation

A circumnavigation is a journey that circles a definable geographical feature (for example, a mountain range), covers at least 90% of its extent, and has its start and finish at the same point.

partial circumavigation

A partial circumnavigation is a journey that circles a definable geographical feature and covers less than 90 % of its extent or does not start and finish at the same point.

Inner Circumavigation

An internal circumnavigation is a voyage that circles a definable geographical feature (for example, a frozen lake) along its inner perimeter, covers more than 90% of the feature’s extent, and has its origin and destination at the same point.

Partial Inner Circumnavigation

An internal part circumnavigation is a voyage that circles a definable geographical feature along its inner perimeter and covers less than 90 % of its extent of the feature or does not start and finish at the same point.

Loop (Full Loop)

A full loop or lap is a path that circles an undefined area and has its start and finish at the same point. Usually only covered by snow kiters or wind craft sailors.

open loop

An open loop is a curved path that partially circles an undefined area or whose start and finish are at different points.

The Continous Journey

A continuous journey is not divided into several individual spatio-temporal segments.

Discontinous Journey

A non-continuous trip is divided into several spatio-temporal individual segments.

Distances

Travel distances are usually measured as the daily distances between camps. In addition, more detailed waypoint intervals can be specified. In the Arctic Ocean, ice drift is taken into account by the changing camp positions.

Support/Aid (assistance)

A polar journey is considered “unsupported” when

- it does not receive physical assistance or supplies (provisions, fuel, equipment, etc.) from outside or others (“resupplied”).

- no depots are made before the trip or by others (depots made by oneself during a trip are not considered as support, but as “self-supplied”).

- no aircraft or motorised escort vehicle is used to provide physical or psychological support.

- no team member is evacuated.

- no buildings, aircraft or vehicles or tents other than their own are used during the journey.

- no roads, tracks, vehicle lanes or marked routes are used except for established routes at stations or camps as directed by authorities (use of the entire Leverett Glacier with the established South Pole Traverse is classified as support); and

- nothing is left behind except, at most, human waste.

A trip is considered “supported” if it fails any of the above or is not specifically designated as “unsupported”. Using GPS data or route tracks for orientation is common today, but is considered a greater form of dependency than traveling without GPS data known in advance. The use of satellite telephones, weather and ice forecasts or external standby advisors is also accepted as an aid and is not considered as assistance. Since many polar expeditions today cannot be carried out without external means of communication, the greatest possible reduction of external communication and independence are fundamental quality characteristics of high-quality undertakings with a high degree of – also psychological – self-sufficiency. Professional leadership is also not classified as support. However, a fair description should include the indication that it is a guided tour. If a pre-description of a journey is no longer accurate after it has been carried out, it should be amended to reflect the journey actually made.

Labels

A label is a synthesis of qualifying key terms to succinctly describe polar travel, such as: “South Pole Ski Last Degree Expedition”, “Solo Full Ski Crossing of Antarctica”, “Alternate Return South Pole Snowkite Expedition”, “Inland Wind-Craft Crossing of Antarctica”, “Reverse South Pole Bicycle Expedition”, “Partial Ski Circumnavigation of Ellsworth Mountains”, “Solo Iceskate Inner Circumnavigation of Lake Baikal”, “Reverse Solo Unsupported South Pole Snowkite Expedition”, etc.

Verification

Terminology and guidelines of PECS can be used in general. Claims and data must be credible and verifiable such as GPS tracks, waypoint data, detailed route information, pictures, etc.

For more on PECS, definitions and maps for the Arctic Ocean and Greenland, see www.pec-s.com.

All data have been researched to the best of our ability, but without guarantee of being free of errors.

International Polar Guides Association (IPGA)

As there are no professional regulations for polar guides, the International Polar Guides Association (IPGA) was founded in Svalbard in 2010 with headquarters in Canada and president Eric Philips from Australia. Today it unites 32 of Iceland, Canada, Norway, Austria, Russia, Switzerland, Spain and USA. The goal of the worldwide organization is to educate the public about the qualifications required of leaders for polar ice travel and to identify highly qualified polar leaders through a standardized recognition process that takes into account education, leadership and expedition experience to ensure the highest level of safety and professionalism for clients. And for the professionals, the network offers a platform and mutual support. Because the world for polar riders is huge, but the world of polar riders is small. www.polarguides.org

More on the subject: