Swiss banks may not be the most obvious allies for indigenous communities struggling to survive in Russia’s far north. But their financial clout could push multinationals to change their business practices, argue those who were hit by a major environmental disaster last year.

swissinfo.ch: Dominique Soguel-dit-Picard with input from Igor Petrov

A delegation from the Russian Arctic travelled over 4,800 kilometres to Switzerland this month. High on their agenda was to draw attention to the ongoing consequences of one of the largest oil spills in their country’s history. They want Swiss banks to use their influence to persuade the responsible companies to protect the environment and to consult indigenous communities properly.

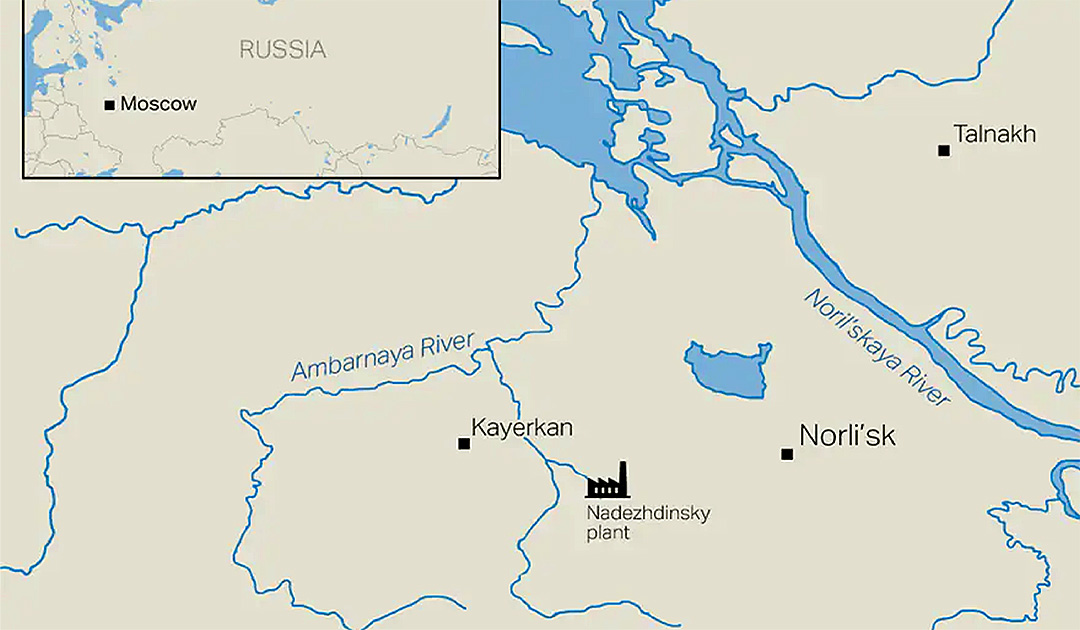

On May 29, 2020, a fuel tank burst near the Siberian city of Norilsk, flooding two local rivers with about 21,000 tons of diesel. The company behind this environmental disaster is Russia’s Norilsk Nickel or Nornickel, the world’s leading producer of refined nickel and palladium.

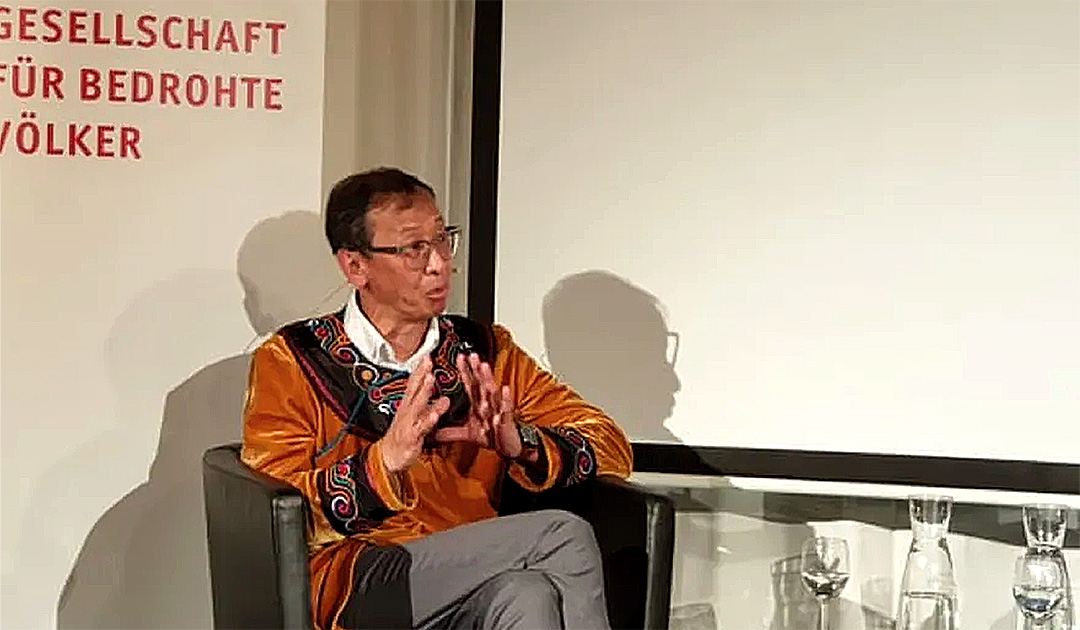

“This oil spill is the tip of the iceberg,” says Rodion Sulyandziga, director of the independent Centre for the Support of Indigenous Peoples of the North. “The pollution and disempowerment of indigenous communities didn’t start a year ago. It’s a long story.”

The diesel disaster in 2020 is both a “social disaster” and an environmental disaster, the human rights activist told SWI swissinfo.ch. It has had devastating consequences for indigenous communities trying to make a living in a difficult habitat through fishing, reindeer herding and hunting. It also affected their ability to trade.

“They have to go far into the tundra to find new fishing and hunting grounds,” Sulyandziga said. “Because of the oil spill, they don’t have much fish or meat. And even if they have [einige], they can’t sell it because it has a special smell … the profit goes down.”

Investments by Credit Suisse and UBS

In 2019, Nornickel had made a revenue of $14 billion (12.5 billion Swiss francs) and a profit of $6 billion. The metals it produces are essential to the booming electric car industry. According to the NGO Society for Threatened Peoples, Switzerland’s largest banks, Credit Suisse and UBS, are together among the ten largest investors in Nornickel. They are also important lenders.

According to Profundo, a Dutch research group, UBS held $45 million worth of Nornickel shares and bonds as of April 2021. Credit Suisse has $27 million in equity in stocks and bonds. It also made loans totaling $268 million.

Both banks indicated that they would not comment on existing or potential customer relationships. “We will not do business if it involves serious environmental or social harm to or, among other things, violations against indigenous peoples,” UBS spokesman Samuel Brandner said, referring to the bank’s sustainability report.

Credit Suisse spokesperson Yannick Orto noted that business transactions with companies in sensitive sectors and industries are subject to a reputational risk review process that takes into account the rights of local communities and the impact on the environment. “Credit Suisse is in regular dialogue with NGOs and other stakeholders in this regard,” he said.

Swiss meeting on environmental pollution

In Switzerland, three Russian activists for indigenous rights met with representatives of Credit Suisse and UBS with the support of the STP Berne. But they encountered closed doors at Nornickel’s subsidiary Metal Trade Overseas AG in Zug, a low-tax Swiss canton popular with commodity traders. They hoped these companies would take responsibility and pressure Nornickel to change course.

“If you invest in a company that is doing dubious business that violates human and land rights, you should be prepared to share responsibility for what is going on at the local level,” Sulyandziga said.

On the Taymyr Peninsula, where Norilsk is located, live about 10,000 indigenous people. Nornickel also has a production facility on Russia’s eastern Kola Peninsula, where the Saami people live. In both regions, corporate pollution is seen as a direct threat to indigenous ways of life.

“They don’t want to cooperate with us,” says Andrey Danilov, director of the Saami Heritage and Development Fund, who took part in a panel discussion organized by the STP in the Swiss capital Bern. “This company is presenting untrue information to its investors and the global community. So we’ve come to inform its partners in Switzerland ourselves.”

Russia’s Norilsk smelter complex in the Arctic Circle has the highest sulphur dioxide (SO2) emissions in the world, according to satellite data from the US space agency NASA commissioned by Greenpeace. The smelters are responsible for more than 50% of all SO2 emissions in the whole of Russia.

Other environmental incidents in the region include the leakage of iron oxides from the Nadeja plant in Norilsk, which, according to the STP, “turned the Daldykan River red”. A 2020 fire at one of the company’s industrial waste sites covered the tundra with smoke that choked flora, fauna and people.

An industrial accident at a Nornickel processing plant in Norilsk also killed three people and injured three others in February this year.

“Nature is poisoned, part of the Sami soul is poisoned,” Danilov said, describing a moonscape of water and contaminated land within 30 kilometers of the town of Monchegorsk, where a Nornickel refining center is located. “We’re already at the edge of Earth. We’re not going anywhere else. We want to save our people and pass on what our ancestors passed on.”

Empty gestures?

Nornickel did not respond to several queries from swissinfo.ch. In a March 21 letter to the Business and Human Rights Resource Center, the company acknowledged that there were “legacy issues” and took “full responsibility” for the diesel spill. It claims to have collected over 90% of the fuel spill.

“Change takes time, but we are determined to see it through and ensure that both our employees and local communities feel safe and fully supported,” the company’s letter said. Nornickel also paid the Russian government a record fine of about 1.62 billion euros (146.2 billion rubles) in damages.

In the same letter, the multinational mentions that 699 people whose livelihoods depend on fishing in Lake Pyasino and the Pyasina River will be paid direct compensation in the amount of 174 million rubles (an average salary in Russia is about 50,000 rubles). He also points to cooperation agreements with three indigenous associations.

“The airport and all kinds of infrastructure are controlled by Nornickel,” Sulyandziga says. “It’s not so easy to fight with a big company like Nornickel [das] located very close to Moscow.”

International supervision

During their visit, the activists also met with Swiss government representatives. They found a sympathetic ear from Ambassador Stefan Estermann, who represents Switzerland as an observer nation in the Arctic Council, an intergovernmental body of the eight governments and indigenous representatives of the Arctic.

“It is important that the peoples of the Arctic be fully consulted on any resource extraction or mining activities,” the ambassador said, referring to a 2007 United Nations declaration.

He also pointed to the need for Swiss companies operating in the region to conduct human rights due diligence and “investigate impacts that they cause or may contribute to through their own activities or that are directly related to their business activities, products or services, or through their business relationships.”

When Russia took over the chairmanship of the Arctic Council in May, it made sustainable development a top priority – one that must be balanced with ambitious resource extraction goals. Last year, Russian President Vladimir Putin unveiled $300 billion in incentives for new oil and gas projects north of the Arctic Circle.

“The Nornickel industrial and environmental disaster has highlighted several challenges affecting the Arctic region,” Estermann said.

“Economic activity in the region is growing, especially as rapid changes are underway in the Arctic. This increases the risk of disasters, and when disasters do occur, the impacts and costs to responsible industry, affected populations, and fragile ecosystems increase very quickly.”

swissinfo.ch, Dominique Soguel-dit-Picard with input from Igor Petrov

More on the subject: