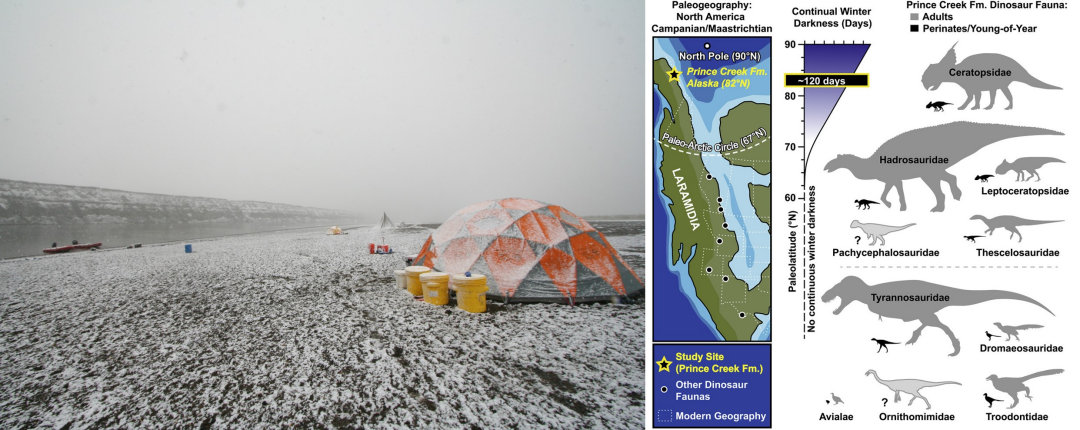

The “Jurassic” series has shaped the image of dinosaurs in warm, sometimes tropical environments in people’s minds. As reptiles, the animals were cold-blooded and needed an appropriate environment. But the reality is different, as a US and Canadian research team could show: Dinosaurs lived year-round in the Arctic, even in the winter-cold dark season.

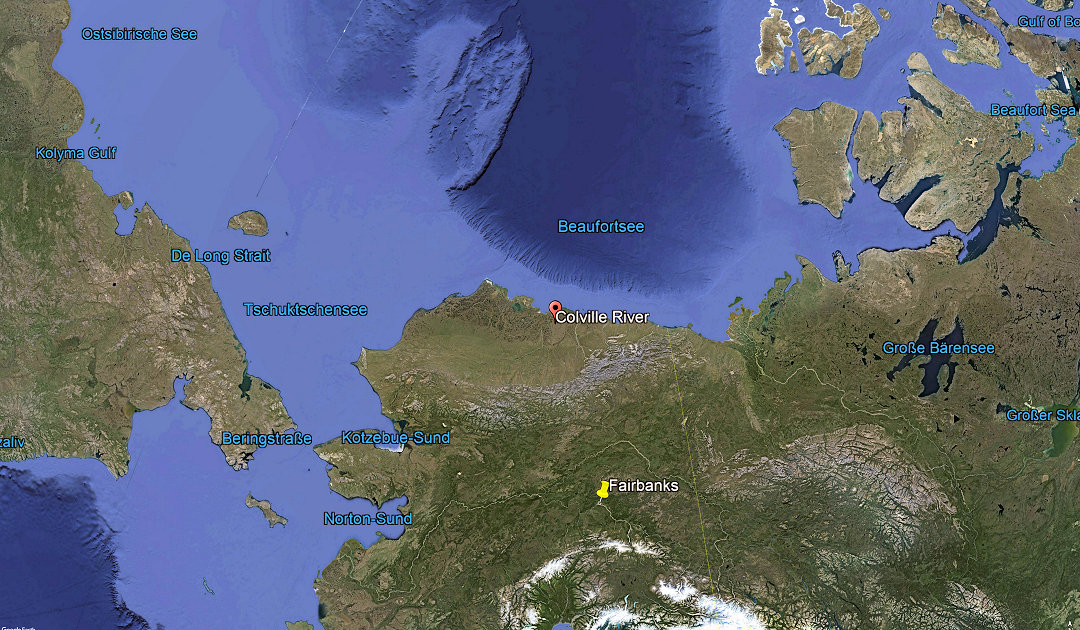

The team, led by Dr. Pat Druckenmiller of the University of Alaska’s Museum of the North and Professor Gregory Erickson of Florida State University, discovered fossils of babies from seven different dinosaur groups on the banks of the Colville River in northern Alaska. The so-called Prince Creek Formation contained small bones, teeth and fragments of baby dinosaurs from the late Cretaceous period that had either just hatched or were even still in the egg when they had died. A total of seventy percent of all known dinosaur families are represented in the finds. “It was like being in a prehistoric maternity ward,” Gregory Erickson explains in a press release.

The find is a real surprise for science. For it was known up to now that dinosaurs had migrated as far as the Arctic and that at least one group had even bred here. But the variety of species that the find has brought to light surprises even the experts. “One of the biggest mysteries about Arctic dinosaurs was whether they seasonally migrated up to the North or were year-round denizens,” Gregroy Erickson says. “We now have unequivocal evidence they were nesting up there as well. ,” added lead author Patrick Druckenmiller. The evidence for this is provided by the numerous small fossil remains of seven different dinosaur groups. Among the finds were both large and small dinosaur species belonging to well-known groups such as the Tyrannosauridae, the Ceratopsidae and the Hadrosauridae and Dromaeosauridae, which have already been recorded in the Arctic.

Greg Erickson (l) & Pat Druckenmiller (r) at the excavations. Arctic conditions, but which showed how great the diversity of dinosaurs was in the Arctic at that time. The Colville River empties into the Beaufort Sea in the North Slope. The Prince Creek Formatioon is located a little further inland on the river

But the really strenuous work was the identification of the small remains from the Cretaceous period. Using microscopes and binoculars, the pieces were separated from remaining sand grains, catalogued, and then compared with known dinosaur remains from species living further south with the help of Canadian scientists. This revealed not only dinosaur species close to modern birds, but also non-avian dinosaur species, a big surprise that raises further questions. Particularly the way in which the animals, which had previously been regarded as cold-blooded, had dealt with the conditions of the Arctic is interesting.

Since a breeding period of three to six months is assumed for dinosaurs and the summers in the region where they were found were also short at that time, but the winters were dark and cold, there was not enough time for the young to undertake long migrations back to the south at the end of the summer. Consequently, the animals must have either lived here all year or grown so fast that they were big enough to survive the long migration back. What is certain is that while the find has solved a long-standing question, it has also raised umpteen new questions. So the dinosaurs of the Arctic will continue to keep researchers busy… and perhaps provide new material for Hollywood filmmakers.

Dr Michael Wenger, PolarJournal

More on the subject: