A new computer modeling technique developed jointly at the University of Vienna and the Norwegian Institute of Air Research (NILU) allows backward calculation of the atmospheric transport of historical emissions in ice cores and thus to determine the sources of contaminants found in the ice. In their recent publication in Nature, an international team of scientists with the participation of Andreas Stohl proved that the burning of New Zealand’s forests from the 13th century onwards by the Māori was the reason for soot deposits in Antarctica. The ice cores come from field expeditions carried out by the Alfred Wegener Institute and the British Antarctic Survey (BAS).

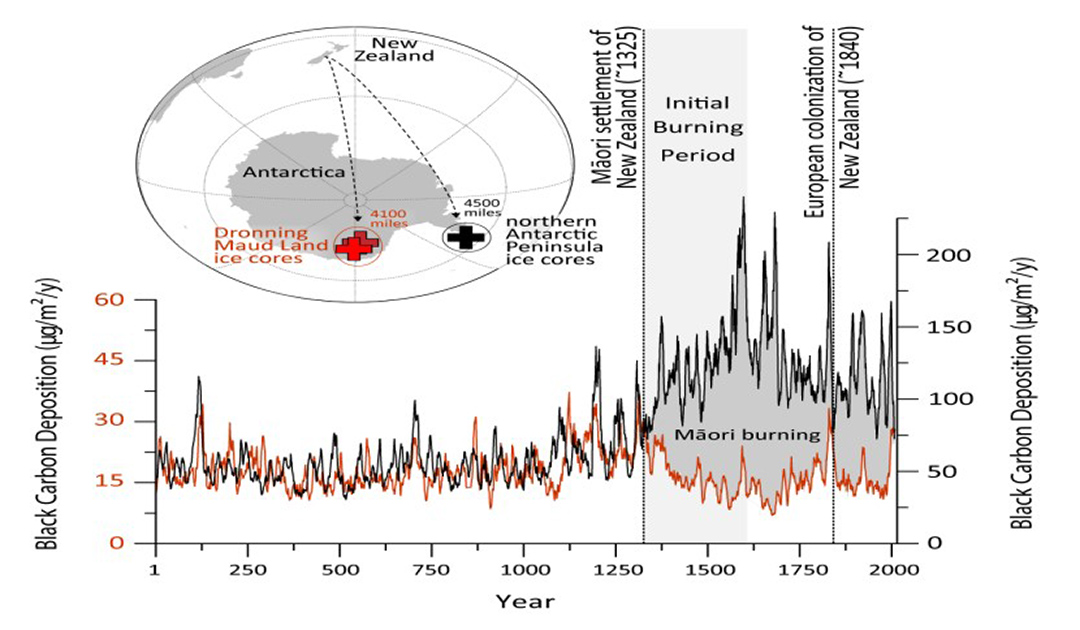

A few years ago, scientists at the Desert Research Institute in the U.S. found a strange signal in an ice core from the Antarctic Peninsula: concentrations of black carbon, usually referred to as soot, began to increase significantly around the year 1300. Soot is formed when biomass or fossil fuels are burned. Since this date coincides fairly closely with the first settlement of New Zealand by the Māori, the assumption arose that the burning of New Zealand’s forests by the Māori was the reason for the soot deposits.

With the technique of atmospheric transport modeling, it has been possible to verify this theory. In particular, it was curious that the increase in soot deposition was not seen in other ice cores in East Antarctica. “Backward calculations with our transport model from all these ice cores showed that the soot deposits on the Antarctic Peninsula in the simultaneous absence of such deposits in East Antarctica can only be explained by soot emissions in Patagonia, Tasmania and New Zealand,” explains Andreas Stohl of the University of Vienna: “We were able to exclude areas further north in Africa, Australia or, for example, the Amazon region as source regions, as these would have caused a similar increase in soot deposition in East Antarctica as on the Antarctic Peninsula.”

Finally, analyses of sediments from lakes in Patagonia, Tasmania and New Zealand showed an increase in charcoal deposits only in New Zealand 700 years ago. It was thus clear that the coincidence of the arrival of the Māori in New Zealand and the increase in soot concentrations in the Antarctic Peninsula, 6,000 km away, was no coincidence.

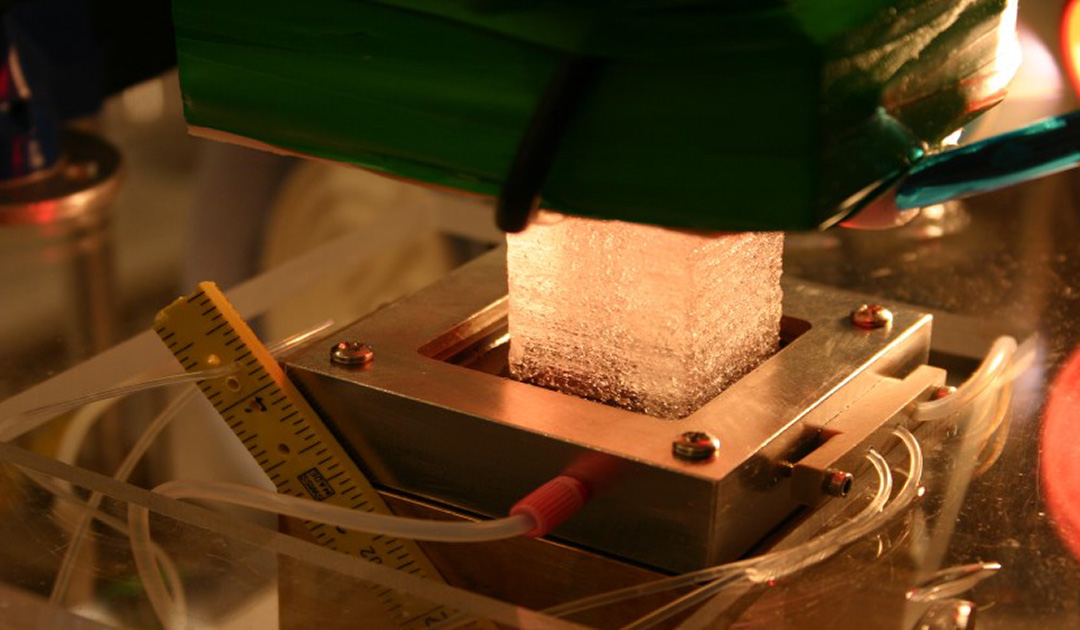

“The idea that humans caused a significant change in atmospheric soot concentrations by burning forests as early as 700 years ago is very surprising,” said Joe McConnell, lead author of the study and responsible for the ice core analyses.

The results provide important insights into the Earth’s atmosphere and climate. Although it is often assumed that human influences on planet Earth were negligible in pre-industrial times, this study provides new evidence that human activities influenced the Earth’s atmosphere and possibly its climate much earlier and on much larger scales than previously thought.

“Ice core records are very important for learning more about human impacts on the environment in the past,” McConnell said. “Even the most remote parts of the Earth were not necessarily pristine in pre-industrial times.”

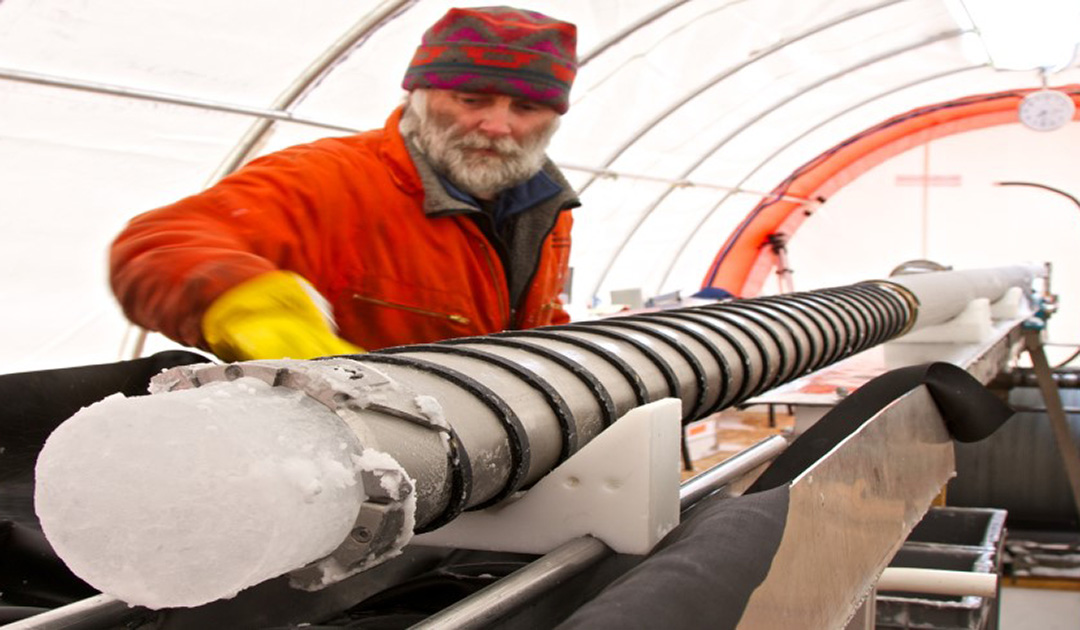

“Ice cores have the invaluable advantage that they can be dated very precisely and are far away from local sources of possible contamination. Thus, they trace an almost perfect image of the atmosphere of the past, even over long distances,” adds Johannes Freitag, co-author of the study and responsible for ice core drilling at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) Bremerhaven.

The results also allow more accurate conclusions about the timing of Māori arrival in New Zealand, one of the last habitable places on Earth to be settled by humans. This date has previously varied from the 13th to the 14th century, but the more precise dating made possible by the ice core measurements shows the start of large-scale burning by early Māori in New Zealand around 1297, with an uncertainty range of about 30 years.

Press release of the University of Vienna