Fossil fuels are harmful to the climate and contribute substantially to the Arctic being one of the most warming regions on earth. Unfortunately, however, large quantities of fossil fuels are still lying in the shelf regions of the northern seas. And it is precisely these that some Arctic nations want to continue to exploit, despite all the concerns. This includes Norway, whose prosperity is largely due to “black gold”. But now, in its new and comprehensive Arctic strategy, the EU has made it clear that it will do everything in its power to ensure that these raw materials remain underground in the future. Another dispute between the partners seems inevitable.

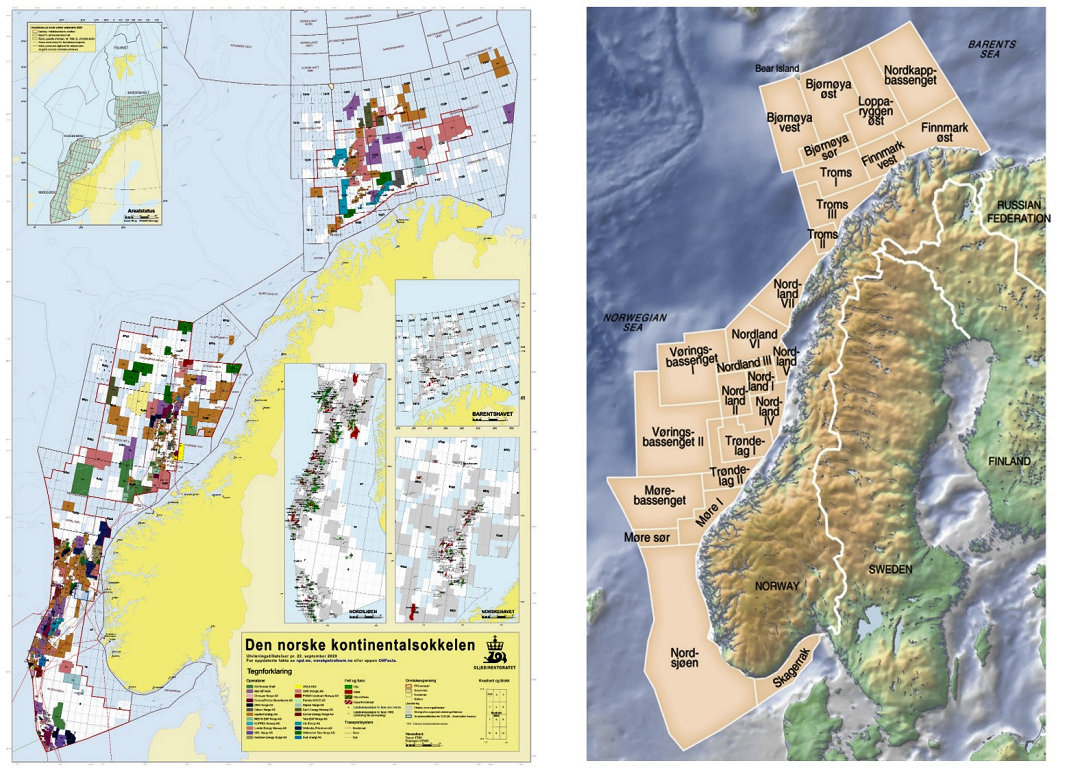

The new Norwegian government under Social Democratic Prime Minister Jonas Gahr Støre took up its work last Wednesday and has already made clear the direction the country is to take in the coming years. Of particular interest are energy and environmental policy, the relevant ministries of which are headed by Prime Minister Støre’s party colleagues, Marte Mjøs Persen as Energy Minister and Espen Barth Eide as Environment Minister. This is because the government has stated that its climate and environmental policies will be aimed at becoming completely carbon neutral by 2050, while at the same time being “just”. But on the other hand, they want to hold on to oil production and ensure that the industry does not disappear into oblivion. The government stated that it will “prepare the ground for a continued high level of activity on the shelf.” This means that the existing licensing policy for production in Arctic waters will be maintained. The previous conservative government had already done this and auctioned off licenses for production near the Svalbard archipelago. However, the hoped-for success failed to materialize at that time.

With its decision to stick to its production plans, Norway joins the list of Arctic states such as the US, Canada and Russia that are also drilling for oil and gas in their Arctic territories. Greenland, on the other hand, has already declared an exploitation stop in its waters, and Iceland, Sweden and Finland are not averse to halting extractions either. Support for these plans has recently come from the EU in Brussels. In its recently published Arctic strategy, the latter clearly advocated that “all fossil fuels have to remain in the ground”, de facto as a halt to all extraction activities. At this year’s Arctic Circle Assembly, the EU Commissioner for Fisheries and Oceans, Virginijus Sinkevicius, and the EU Ambassador for the Arctic, Michael Mann, reiterated the EU’s position. Sinkevicius very confidently countered the accusation that this would eliminate an important branch of the economy by saying that rising temperatures and climate change are already doing this. While acknowledging the fact that many jobs depend on it and that the whole thing will not be “a walk in the park”. But, he said, they are willing to cooperate on all levels with those who want out. But the EU would continue to push the stop at partners.

The two opposing statements from the EU and Norway are likely to be another bone of contention between the two parties. The EU and Norway are already in dispute over fishing rights in Svalbard. There are also different positions on the importation of some artisanal products from Arctic peoples, such as sealskins. It is not clear whether and how this will also affect the EU’s still pending application to become an observer in the Arctic Council. As a non-EU member, Norway faces a front of three EU member states (Denmark, Finland, Sweden) and six observer states (Germany, France, Poland, Italy, the Netherlands and Spain), but can certainly count on the support of the USA, Canada and the Council Presidency Russia with regard to the extraction of raw materials. For it is precisely with the latter state that the new Norwegian government wants to intensify bilateral cooperation. But whether this will influence the EU, which is pushing ahead with its Arctic policy with fresh impetus, remains to be seen in the coming period. What is certain is that in the Arctic, not only the climate will heat up further in the future.

Dr Michael Wenger, PolarJournal

More on the subject: