While politicians and environmental groups struggle to keep global temperature rise below 1.5 °C, the Arctic is warming three times faster than the rest of the world. Arctic species are likely to increasingly retreat northward in search of colder waters, while more temperate species will predominate in the Arctic and subarctic. Shifts in marine species have already been observed in some regions. This will also change the diet for polar bears (Ursus maritimus), according to a recent publication.

To document the change, researchers examined the fatty tissue of polar bears to determine how their diets have changed. This is a common practice that can provide information about what prey the polar bears have consumed.

“The Arctic is changing. It is changing at a very rapid pace, especially in comparison to really any other region of the world. Temperatures are warming faster,” Melissa Galicia, a PhD student in York University’s Department of Biology and one of the study’s authors, told Ars TECHNICA. “The ice is declining. Sea ice is becoming more fragmented. The water temperatures are warming. You’re getting an ecosystem that is changing rapidly, and all of the species within that ecosystem also need to adapt.”

What does this mean for the polar bears?

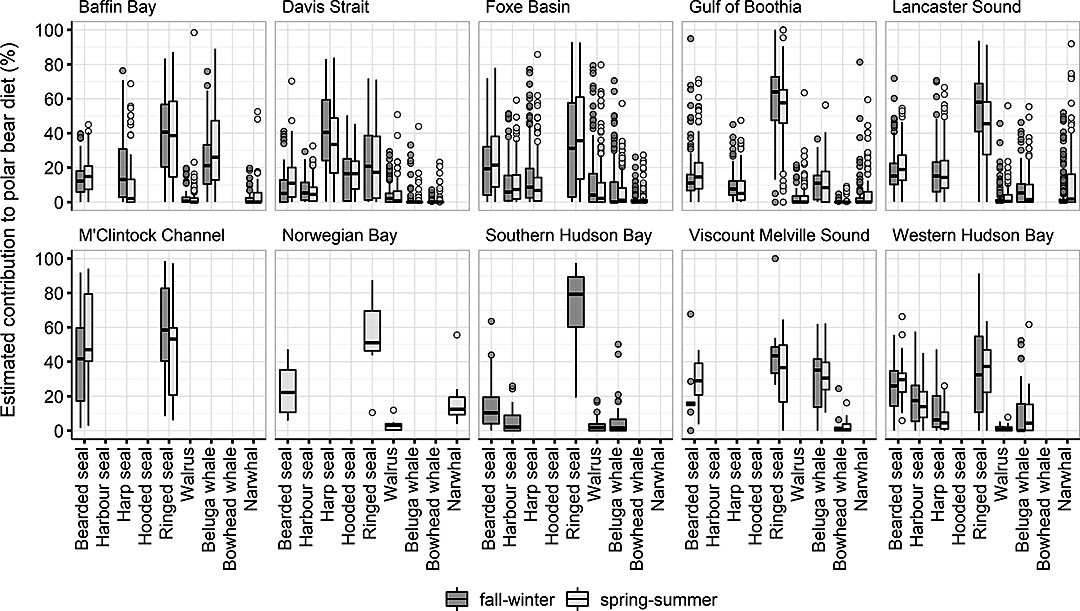

Polar bears are predators with a circumpolar distribution. Although often characterized as specialized predators of ringed seals, polar bears are capable of flexible foraging when multiple prey species are spatially and temporally available.

The objective of the study was to investigate the spatial structure of the composition of the diet of polar bears in Canada’s largest province, Nunavut. The area was limited to latitudes 60°W to 110°W and longitudes 55°N to 80°N.

The researchers used fatty acid profiles of polar bears and their prey to identify local and seasonal conditions in diet composition.

In Nunavut, one of Canada’s northern territories, Inuit are allowed to hunt polar bears. Over the years, Inuit hunters have sent muscle and fat samples to York University. It is fatty tissue samples from 2010 to 2018 that Melissa Galicia and her team studied. The researchers analyzed fatty tissue samples from polar bears from ten Canadian polar bear subpopulations. In total, samples from 1,570 polar bears were sent in.

According to Galicia, there are about 70 different types of fatty acids in marine ecosystems. Because of this diversity, each bear’s fat sample has a kind of unique signature based on its diet. The researchers ran the samples through a nutritional model to figure out the proportions of each bear’s diet. For example, the fat might indicate that a bear ate 50 percent ringed seal, 25 percent beluga whale and 25 percent bearded seal.

Also found were traces of bowhead whales, which are not part of the natural diet of polar bears. The researchers said that orcas hunt bowhead whales and leave behind parts of whale carcasses for polar bears to feed on. Orcas are one of the few species of marine animals that are increasingly moving north due to climate change.

Heiner Kubny, PolarJournal

Link to the study from: ScienceDirect