Plumes of dust from Greenland heralding the coming of winter are made up a material that scientists say can be used elsewhere.

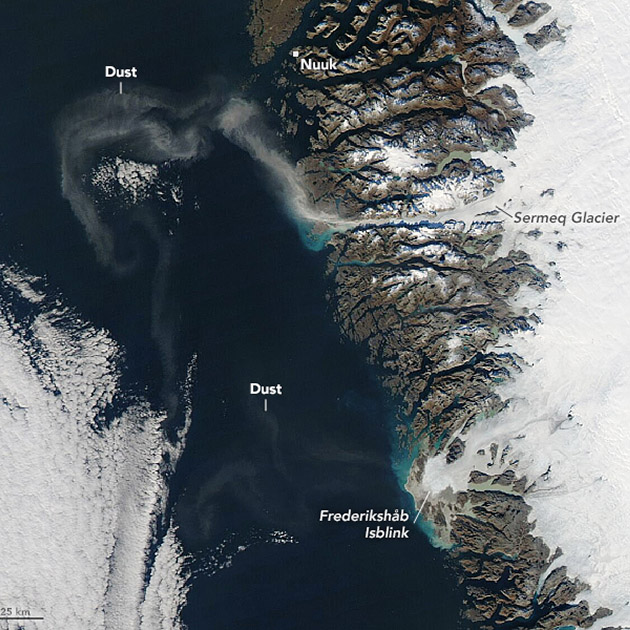

On October 18, Nasa satellites captured a picture of three enormous plumes tailing off Greenland’s western coast. To the untrained eye, these plumes are simply dust. But the material, known by several names, including glacial silt, glacial rock flour and rock dust, is in fact a nutrient-rich powder that has a number of uses, including capturing carbon-dioxide and replenishing depleted soils, scientists say.

Glacial silt can be found in enormous quantities along Greenland’s coast. During the summer it washes into coastal waters as rapidly moving streams and rivers carry silt-laden meltwater away from the ice sheet and toward the coast.

By autumn, cooler temperatures cause melting to slow and rivers to recede, leaving the silt high and dry. As winds streaming down from the ice cap blow over the silt, it gets picked up and carried out to sea. During winter, snow covering the ground prevents the wind from lifting it.

In the close-up image above at right, the dust can be seen as low-altitude plumes that stretching hundreds of kilometres out to sea from the area around the Frederikshåb Isblink and Sermeq glaciers.

Normally, the silt is something of a nuisance locally because of the sheer amount of it and the mud it creates. But as scientists gain a better understanding of its useful properties, Greenland, they suggest, could begin exporting it to parts of the world that suffer from depleted soils.

The potential of glacial silt to enrich soils has long been understood. At sea, for example, it makes it possible for otherwise nutrient-poor parts of the ocean to support life, sometimes leading to algal blooms. While, on land, it can feed ice algae, normally a key part of the food chain, but, when present in large numbers, can darken the surface of sea and land ice, which hastens its melting by reducing its ability to reflect solar energy. As the pace of glacial melting picks up, both of these processes are intensifying.

Similarly, some of the world’s most fertile cropland can be found in the Northern Hemisphere along a belt that closely follows the edge of the icecap that formed during the most recent ice age. As that icecap melted and retreated, the glacial silt it created was left behind to enrichen the soil.

Kevin McGwin is a journalist who has been writing about Greenland and the Arctic since 2006. Between 2013 and 2017, he was editor of The Arctic Journal. His latest project, The Rasmussen, continues in the spirit of The Arctic Journal, offering “regional news with a global perspective.” In addition, he regularly writes articles for Arctic Today, occasionally contributes to the Greenlandic weekly newspapers Sermitsiaq AG and has written for a variety of other websites related to the Arctic.

Website: The Rasmussen