Orcas and false killer whales(Orcinus orca and Pseudorca crassidens) living today are known to feed on other marine mammals as well. Orcas even prey on the largest creatures on Earth – blue whales. A recent fossil find of an early killer whale that lived in the Pleistocene is now thought to show that back one and a half million years ago, large dolphins preyed on fish, not other marine mammals. The study, conducted by scientists at the University of Pisa, Italy, and the College of Osteopathic Medicine at the New York Institute of Technology, USA, was published in the journal Current Biology.

So far, only very few fossils of early killer whales have been found and the knowledge about the evolution of the two species, which belong to the family of dolphins, is scarce accordingly. This makes the discovery of the remains of a previously unknown dolphin on the Greek island of Rhodes in 2020, estimated to have lived one and a half million years ago in the Pleistocene, all the more astonishing. They are believed to provide the first unequivocal fossil evidence of the origins of the false killer whale. The newly discovered, long extinct species was given the scientific name Rododelphis stamatiadisi, after its Rhodes locality and its discoverer, the paleontologist Polychronis Stamatiadis.

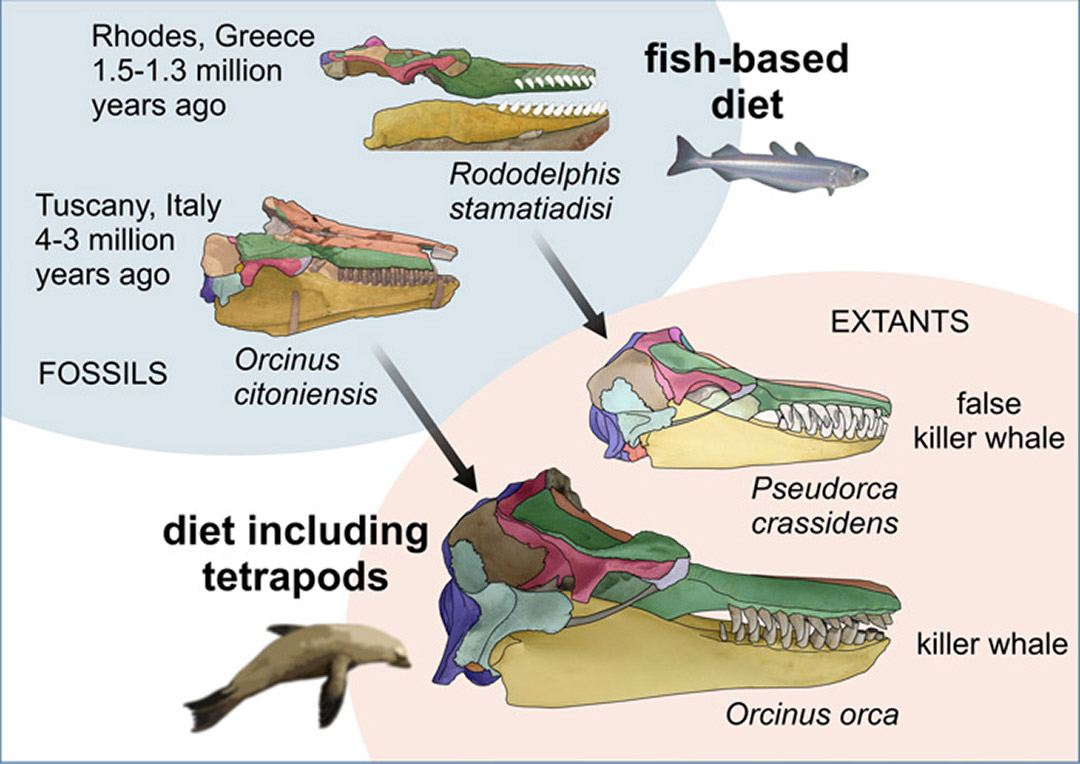

A comparison of the partial skeleton of Rododelphis with the anatomy of orcas and lesser killer whales, and with the only known fossil relative of orcas, Orcinus citoniensis, revealed that Rododelphis, with a length of nearly four meters and a weight of about 500 kilograms, is about the same size as the false killer whales living today. The scientists were even able to draw a conclusion about his last meal, which, according to the five otholiths (small stones in the ear of fish) next to the fossil, must have consisted of blue whiting (Micromesistius poutassou).

Unlike orcas and false killer whales living today, which feed on other marine mammals, fish, or squid depending on the population, the teeth of Rododelphis and Orcinus citoniensis had only fine scratches and hardly any chipping, indicating that these two species fed on fish. The teeth of modern killer whales, on the other hand, show larger scratches and chips that are often produced when prey with bony skeletons are eaten.

Assuming that the less severe tooth wear in the two fossil skeletal finds applies to all representatives of the species living at that time, the findings from this study contradict the assumption that the large baleen whales (e.g., blue whales, fin whales, etc.) had developed these enormous body sizes to avoid predation. The first giant whales appeared from 3.6 million years ago. According to the authors, their findings suggest that killer whales did not hunt other marine mammals until much later. They assume that orcas began hunting other whales in the last three million years ago, and small killer whales in the last one and a half million years.

In a New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) report on the study, Jonathan Geisler, a professor at NYIT’s College of Osteopathic Medicine, an expert on marine mammal evolution and co-author of the study, says, “Diversification of the oceanic dolphin family occurred within the last five million years, but fossil evidence from the Pleistocene is extremely rare. With Rododelphis, we are now beginning to fill this gap and better understand the repeated evolution of feeding adaptations in oceanic dolphins – in other words, how orcas and pinnipeds separately evolved similar cranial anatomy and behavior to feed on other marine mammals.”

The authors hope to conduct further excavations for fossil skeletons in Greece and Italy in the future to continue their research.

Julia Hager, PolarJournal

Link to the study: Giovanni Bianucci, Jonathan H. Geisler, Sara Citron, Alberto Collareta. The origins of the killer whale ecomorph. Current Biology, 2022; DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.02.041.

More on the subject: