Just last week, weather stations reported record temperatures in the Arctic and Antarctic. As now revealed by satellite images, a complete ice shelf collapsed in East Antarctica for the first time — and shortly before the Antarctic heatwave reached the region. The Conger Ice Shelf, with its area of 1,200 square kilometers, is a lot smaller than, for example, the Larsen B Ice Shelf, which broke off in the Weddell Sea in early 2002, but scientists are surprised that the collapse happened so quickly in East Antarctica, which is still considered quite climate-stable.

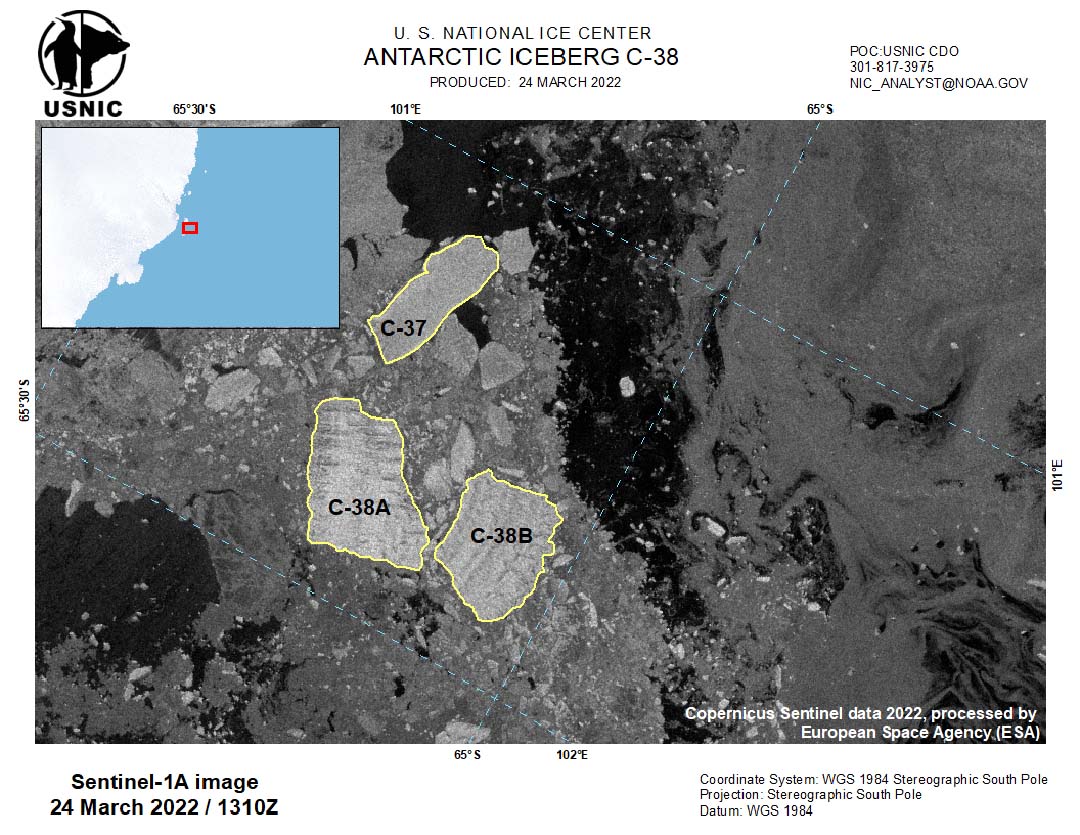

The Conger Ice Shelf, in Wilkes Land, was about the size of Rome. It completely collapsed within a few days around March 15, according to satellite data, scientists said on Friday. Record temperatures during the heatwave that swept the region were not measured until three days later. Satellite data from the Copernicus Sentinel-1 mission showed that the movement of the ice shelf began between March 5 and March 7, according to Peter Neff, a glaciologist and assistant research professor at the University of Minnesota. The resulting iceberg was named C-38 and has since broken into two pieces, C-38A and C-38B.

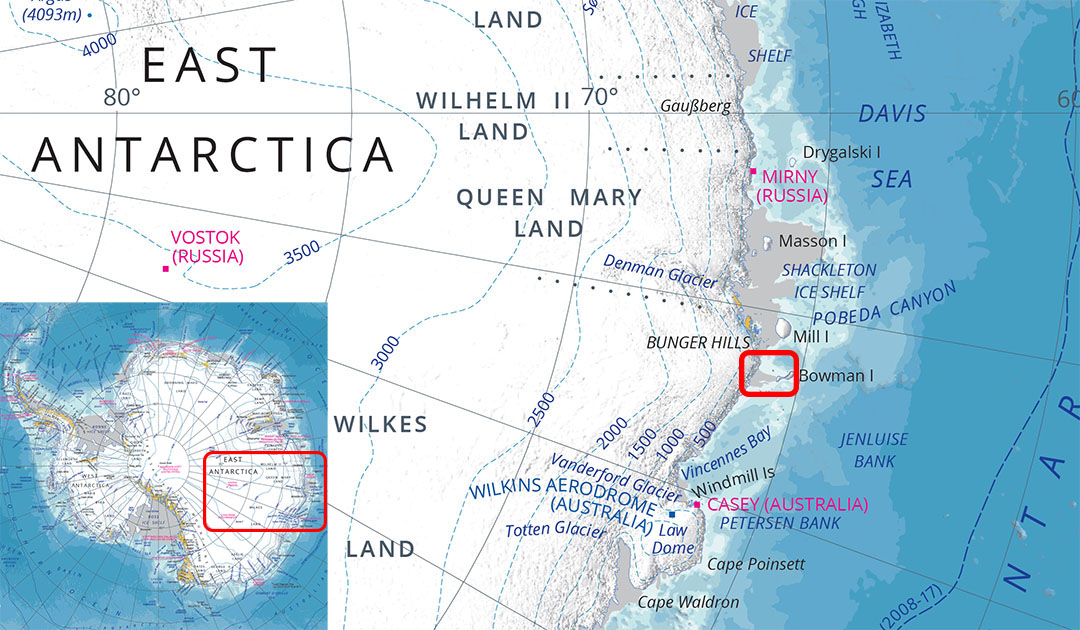

The Conger Ice Shelf was located between the Antarctic continent and Bowman Island. Ice shelves and glaciers in East Antarctica have been relatively stable so far. But now climate change seems to have arrived there as well. Map: Australian Antarctic Division

By early 2020, the Conger Ice Shelf had only gradually decreased in size, Dr Catherine Colello Walker, an Earth and planetary scientist at Nasa and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, told The Guardian. In the first two months of this year, however, about half of the ice shelf has already been lost, she said. “It won’t have huge effects, most likely, but it’s a sign of what might be coming,” Walker said. The glacier behind the Conger Ice Shelf is comparatively small, so the impact on sea level should be small.

Scientists have yet to investigate whether the collapse of the ice shelf is related to the current heatwave. According to Professor Andrew Mackintosh, the head of the School of Earth, Atmosphere and Environment at Monash University, the ocean melted the Conger Ice Shelf significantly from below, which may have aided the collapse. “The collapse itself, however, may have been driven by surface melting as a result of the extremely warm temperatures recently recorded in this region. More evidence is needed to link this collapse to the recent warming,” Mackintosh said.

Professor Matt King, who leads Australia’s Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science, said: “The speed of the breakup of [the Conger] ice shelf reminds us that things can change quickly. Our carbon emissions will have an impact in Antarctica, and Antarctica will come back to bite the rest of the world’s coastlines and it may happen faster than we think.”

Julia Hager, PolarJournal

More about this topic