“That’s quite complicated,” is a response I hear more often when I ask scientists about their research. And each time, this statement raises more questions in me than if one had simply explained the research branch to me in a professionally firm manner. I am a teacher for geography and German at a comprehensive school in Hanover, where you can achieve any qualification from the special school leaving certificate after grade 9 to the Abitur and learn together in an inclusive way.

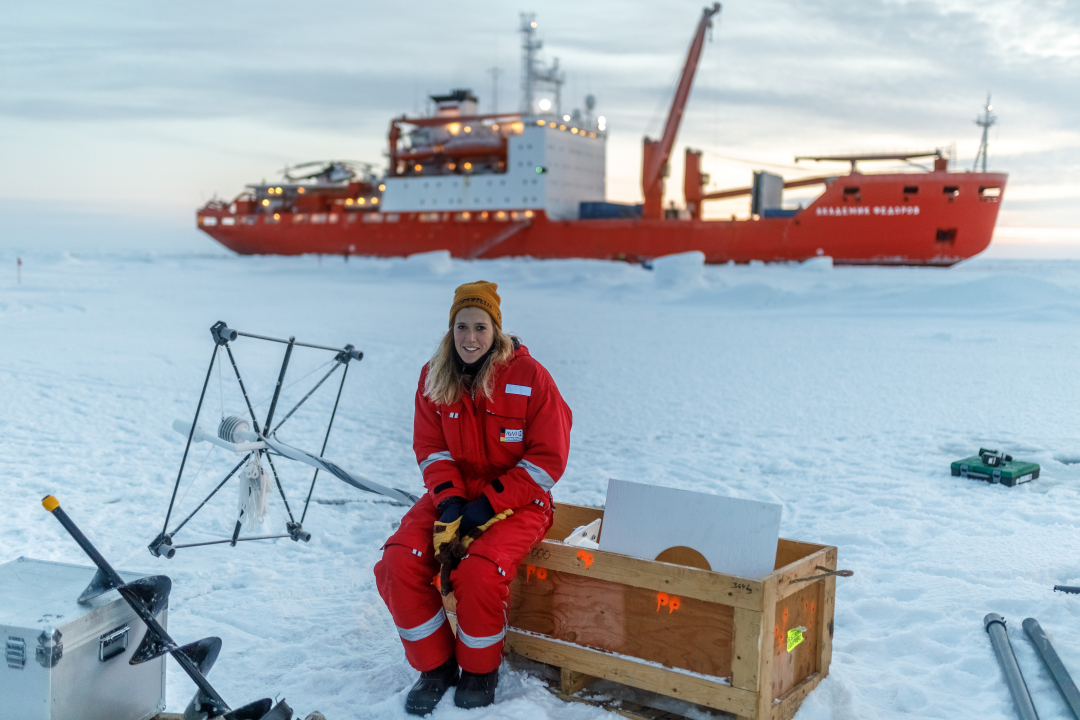

I studied in Munich, where I also worked as a journalist for various media companies for many years. I completed my traineeship in Weilheim, Starnberg and Munich at different grammar schools. Shortly before the end of my education, a friend at the University of Munich showed me the call to participate in a polar expedition. Two German teachers were sought for the MOSAiC expedition, who were to accompany the voyage on an escort ship for the first six weeks and create teaching materials during this time. As I had already written my thesis at university about glacier retreat worldwide and had traveled to Iceland several times with great enthusiasm, I spontaneously applied to the Alfred Wegener Institute, expecting to have to prevail against hundreds of applicants. However, the AWI announcement was so late and so poorly positioned that few faculty took the opportunity and I actually prevailed.

The trip was phenomenal and the insights for me, my students and all those I have since reached in numerous lectures at schools, in clubs and museums or in associations, were of enormous impact. But with every lecture and every conversation among acquaintances and with strangers, it became clearer to me that what the 300 scientists from 17 nations did for a year in the Arctic hardly reaches anyone.

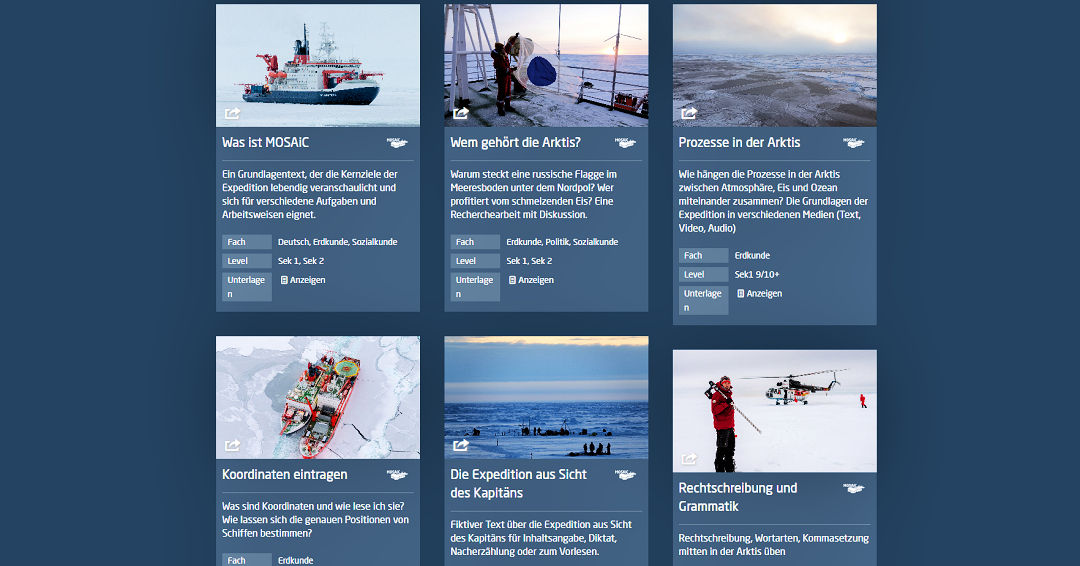

There was a television crew that shot a 180-minute documentary. There were various journalists who reported. Teachers prepare teaching materials, which after much begging also appear on the MOSAiC site, but are unlikely to be found. And Markus Rex is writing a book.

This alone was probably more effort in terms of public relations than on any other expedition before. And yet, much of the population has not even heard of the expedition. I have encountered adults at my lectures who located Antarctica at the North Pole. The knowledge gaps that need to be filled are still enormous.

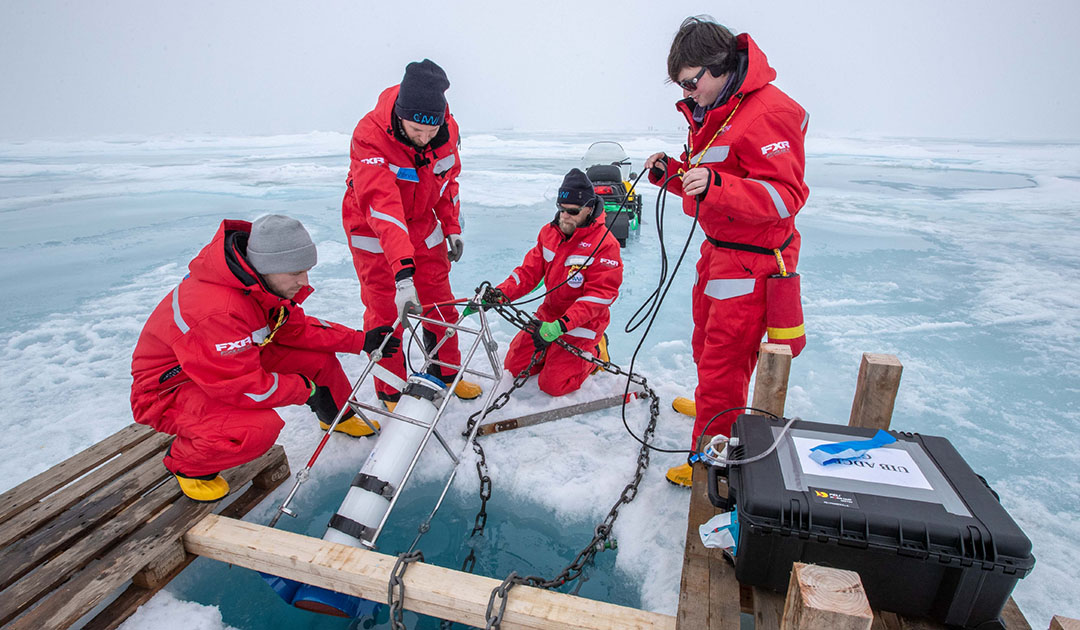

Of course, as a teacher, this is inherently a concern for me. But since I’ve traveled to the Arctic, stood on 50cm thick ice, and helped install an instrument that measures snow accumulation and ice thickness throughout the year, I’m more concerned about the gaps in the general public’s knowledge. Since I have been to the Arctic and made an effort to look over the shoulders of scientists and understand their work, I have become aware of the great distance between what research does and what reaches the population.

Although the 180 million US dollar MOSAiC expedition is largely financed by taxpayers’ money and should therefore be of concern to everyone in the population, most Germans have probably not even heard of it. First and foremost, I do think there should be a right to get results and facts that are funded with our own tax dollars. This could be seen as self-evident or a fundamental right.

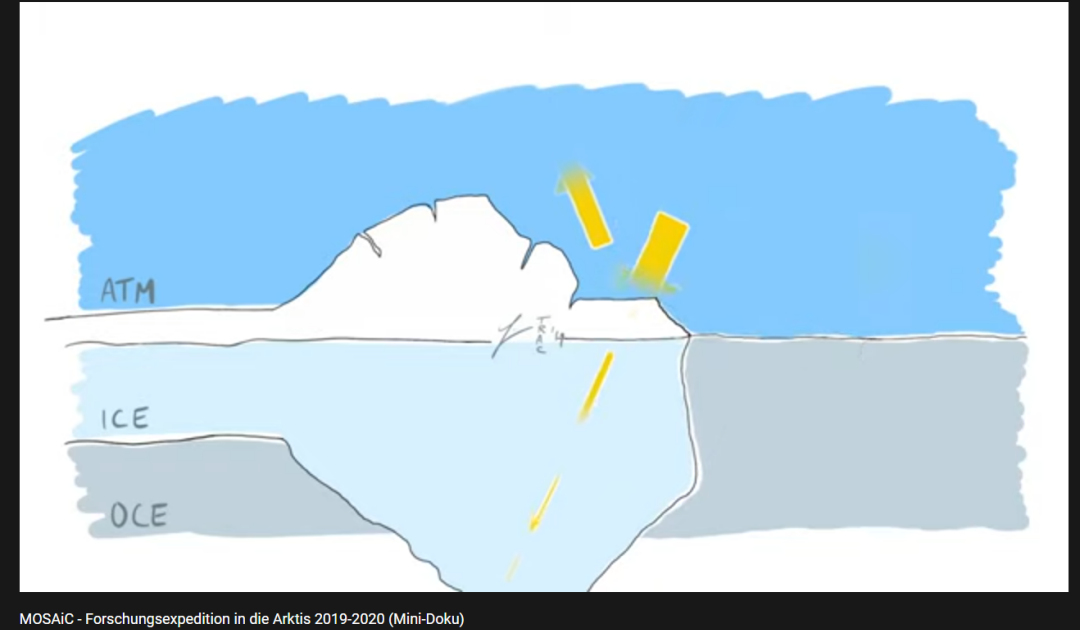

But beyond that, I also think that non-researchers in the general population should know a lot more about what is happening in polar research, for example. From the very basic information to detailed research results. How are algae production, warming, and fish abundance related, and what needs to be done to prevent illegal fishing in the Arctic? What is known about oil and gas reserves in the Arctic and how could a war over resources be prevented? Why does the ice sheet play a role in Arctic warming? Why does snow accumulation affect the melting process of ice? What conclusions can be drawn from the atmospheric composition? Does this perhaps help for completely crazy innovations? What does albedo actually mean and what is it good for? Why doesn’t sea level rise when sea ice in the Arctic is gone? Why is the salt concentration in seawater relevant?

And most importantly, what does Arctic warming have to do with us?

Because I was there and because I have been collecting a lot of information and preparing it for my lectures since I took part in the expedition, I can give myself answers to all these questions. In small films, drawings and a PowerPoint, I travel from hall to classroom and hope to reach as many people as possible. It rarely happens to me that people come up to me who already know all this. Most of them are former polar explorers themselves. Much of us non-researchers have little insight into polar research and research in general. Neither in small details and technical terms nor in large contexts. Since Corona, we’ve been little experts on vaccine approval because it affected all of us ourselves. But what is measured, examined and determined daily at universities and institutes in laboratories and on expeditions, what is invented and developed, is apparently always “too complicated” for us, at least we rarely know. Of course, there are always exciting documentaries, technical articles, science journalism and numerous papers. But all these channels are not mass-market and not necessarily suitable for the young audience that sits across from me every day. And this is not just about children and young people.

Both during my participation in the expedition and afterwards, I experienced again and again how difficult it is for scientists to explain their own work and to break it down in terms of content. As a teacher, that’s exactly what I’m used to: reducing content didactically so that it’s easy to understand without being wrong. Often, from a scientific point of view, this is already close. But this is important to tell something to as many people as possible. I learned that as a teacher, and I wish science would learn that too.

There is a fairly new field called science communication. Of course, it combines areas such as the PR and public relations of an institute, but it also goes a whole step further: scientists* themselves should communicate what they are working on. Whether on their own social media channels or in the institute’s own newsletters. Close cooperation with regional schools or a team of teachers and didacticians is possible. It would be conceivable to cooperate with museums that are well versed in didactic reduction. And regular communication with media houses also falls under this.

Almost everything that was measured or researched during the MOSAiC expedition and even the functions of the devices – that was “quite complicated”, yes, already. But not too complicated. Many initially found it difficult to explain their research to me. Maybe also because it sounds less exciting when you break it down a lot. But don’t worry, polar research doesn’t lose its magic just because a few technical terms are omitted, or processes are presented in a shortened way.

“I went on the expedition to learn about how polar research is done and the impact of climate change on this region. But also to be able to explain at home what the consequences of all this are for us and what we need to do…. Do the same!”

Friederike Krüger

I consider it extremely important that every scientist opens up in some way and to the capacity available with their own work and communicates to the outside world in simple language what significance the results have in a larger context. Of course, the institutes should provide adequate support and the necessary infrastructure. There needs to be much closer collaboration between research and school. I would have liked much more support in the aftermath of my participation to make the materials created more sophisticated, substantive and engaging and also much more widely disseminated. I went on the expedition to learn how polar research is done and what impact climate change has on this region. But also to be able to explain at home what the consequences of all this are for us and what we need to do. I am doing my utmost to achieve this goal. Do the same! After all, that will be your goal – to find answers to important questions that influence people in their decisions. And if we want people to question their behavior, make decisions, take new directions or practice renunciation, they need convincing first-hand data and facts, no matter how old. And it is precisely now, in this time inundated with crises, when natural events are overflowing while war is being waged next door, that science communication is pointing the way forward. I don’t have a manual, but I know: it’s still too little. Hardly anyone reads the IPCC report, too little do the masses know what they should know. Of course, many scientists have been warning for decades. But everyone would have to do it – out of conviction in their own work.

To the website “Working group polar teachers

About the author: Friederike Krüger, 31, teaches geography and German at the IGS Bothfeld in Hanover. In 2019, she participated in the MOSAiC expedition as a polar instructor and accompanied the “Polarstern” on the Russian icebreaker “Akademik Fedorov” for the first six weeks. Friederike Krüger regularly gives talks about the expedition and the effects of climate change, has produced teaching materials(www.mosaic-expedition.org/bildung) and a mini-documentary(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=emAhmmC-9po).