Different nations are focusing greater attention on the Arctic region nowadays, but it is mostly about the political confrontations and strategic decisions rather than scientific collaboration. The Arctic is changing its status as a low tension area. As a result of growing contradiction, the scientific collection and exchange of data are two bottlenecks to the development of international cooperation in the North. It may have severe effects on our understanding of climate change processes, as well as study of local alterations in biodiversity, weather and environment. The recent Russia-Ukraine conflict does not pave the way for smooth scientific collaboration in the Arctic region in the near future.

First, access to northern areas is rendered difficult by its remoteness and the cold and rough climate. Second, political sanctions may have a negative effect on scientific exchange of data and limited participation in international research meetings. Honestly, the Russia-Ukraine conflict is an example that clearly shows how security issues may result in interruption of sharing of knowledge and data by political actions. Thus, some of the recent sanctions imposed by the western countries explicitly prohibit research collaborations with Russian scientists. In March 2022, the European Commision suspended cooperation with Russia on research and innovation. Later in June 2022, the White House wound down scientific collaboration with Russian scientists as well. It relates to all government-affiliated universities and research institutions which have a wide network of multiannual projects on sampling of climate data.

On the one hand, sanctions work as punishment towards the almost entire Russian scientific community and curtail interaction between the world’s institutions. On the other hand, it puts international climate research on hold, and it definitely leaves global data collection with “gaps”. The official collaborations between Russia and the West, which improve the quality and impact of research in general, has been paused indefinitely. In March 2022, seven permanent members of the council took an unprecedented decision declaring they would be “pausing participation in all meetings of the Arctic Council and its subsidiary bodies” (consisting not only of diplomatic staff but scientific working groups) under Russia’s chairmanship . Currently even the 1973 Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears between such Arctic states as Canada, Greenland, Norway, the USA, and Russia , is under question. It took a lot of time and effort to conclude the agreement during the Cold War, but now political decisions are canceling the successful example of international collaboration just in one step.

Field work

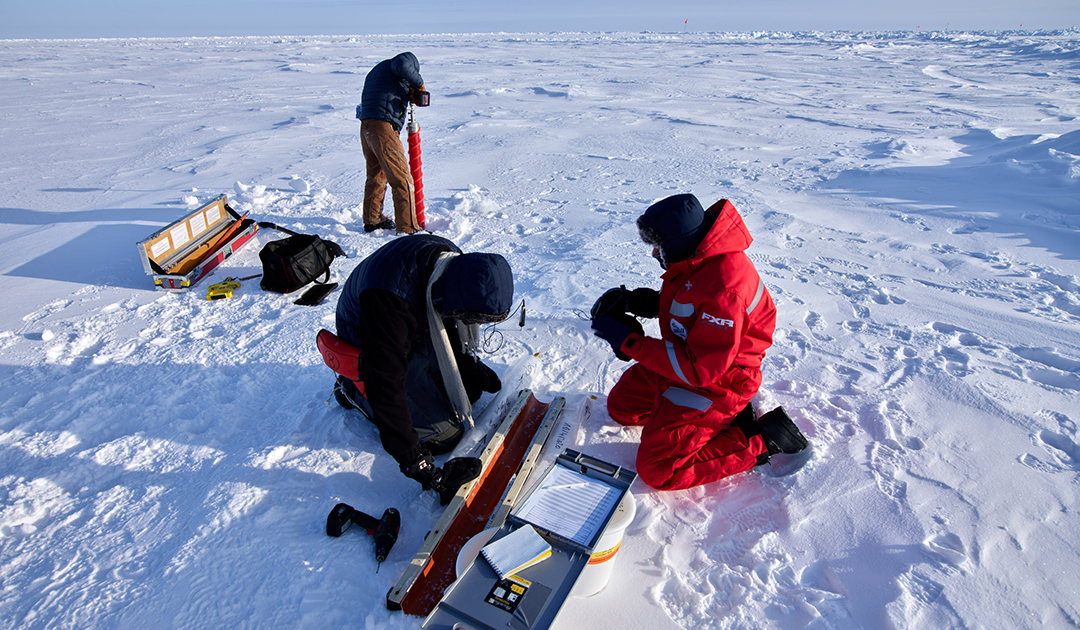

Travel restrictions caused by the Covid pandemics, and later by ban to work with Russian scientists, make scientific exchange and field work extremely challenging in the Arctic region . Such travel implications include temporary suspension of visa issuance and restriction of other immigration rules for Russian citizens. In addition, other countries advise to avoid all travel to Russia due to the impacts of the armed conflict with Ukraine, including limited flight options and restrictions on financial transactions . What it means for the international scientific community: scientists are not able to travel freely to reach remote destinations and collect data, as well as exchange of personnel and data are restricted, access to national databases is limited.

Field work is a vital part of scientific activities for climatologists, marine biologists, glaciologists, and other field specialists. For example, permafrost monitoring and data sharing on thawing frozen grounds require contribution from all the Arctic countries as any data is considered to be valuable for understanding the global impact of climate change on our planet. Also, many nations resource and employ various approaches to studying permafrost, including the growing complexity of scientific modeling.

Lack of citizen science contribution

Shifting political landscape, among other factors, has posed significant implications for the development of the polar expedition cruise market and the cruise industry worldwide recently. Over the past few years, citizen science, i.e. involvement of cruise guests in collecting data, has become a part of tourism with contribution to the scientific community. This kind of tourism can be extremely helpful in monitoring the fragile ecosystems of the Arctic and Antarctica, and data sampling that can tell us about environmental challenges such as ocean acidification, marine pollution, and climate change. As a result of the Russia-Ukraine conflict all major cruise companies have already canceled or postponed some of their planned calls in the North, and have changed previously scheduled Arctic voyages for the next few years. For example, Poseidon Expeditions has confirmed that the tour operator would make changes to their upcoming voyages that include Russia. Also, National Geographic offers a 20-day voyage from Nome in Alaska to Japan without stops in Russia, as it was planned earlier . Clearly, all these factors will negatively affect data collection in remote destinations where at least cruise ships used to sail in previous years.

Planning the future

Researchers and educators have already started to raise the alarm on this matter. For the international scientific community it is clear that “knowledge will be lost if it is not shared and protected”. Research budgets, expeditions and long-term projects are planned in advance, thus this stagnation period in collecting climate data will definitely lead to limited understanding of climate change–driven impacts on the polar regions. It seems like the cooperation between different countries has already become weak and distant nowadays. Is this the right way? We have worked on building bridges for cooperation for such a long time and now all joint efforts are at risk to disappear in history.

Dr. Ekaterina Uryupova is a Senior Fellow at the Arctic Institute. She has been working in the polar regions as a researcher and a polar guide. Her areas of expertise revolve around climate change, marine ecosystems, fisheries, and environmental policy.

More on the topic