Trawling in general has long been heavily criticized by scientists and environmental groups as an unselective fishing method because of the very high percentage of bycatch. Sharks, sea turtles, whales and dolphins often die in the huge nets. Fishing with bottom trawls is particularly problematic, as they destroy the seabed and all organisms living on it. A Norwegian research team has discovered an unexpected number of trawl marks on the seafloor during mapping expeditions north of Svalbard.

Prior to the two mapping expeditions, the team, including researchers from the Geological Survey of Norway and the Norwegian Institute for Marine Research (IMR), expected to find largely untouched seafloor and only occasional marks of bottom trawling. However, what they saw was a completely different picture.

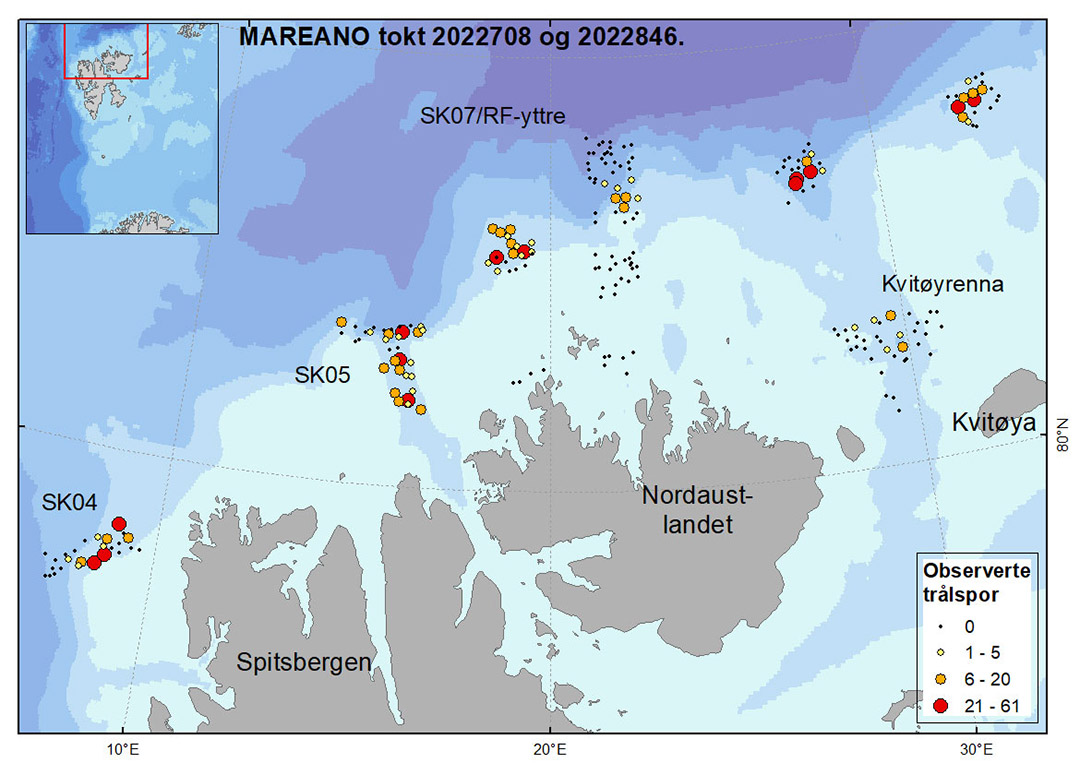

“At the most popular fishing depths, we observed trawl marks at as many as 52 percent of the locations surveyed. In total, we studied 233 locations at varying depths, and overall there were trawl marks at 35 percent of them,” says Pål Buhl-Mortensen, marine scientist and expedition leader in the mapping conducted last summer.

In the region north of Svalbard, bottom trawls have been used for shrimp fishing since the 1970s. How many marks they left behind, however, was unknown until now. “We thought that fishing in these northern waters was something which had increased in recent years, but our observations clearly show that there has been a lot of trawling here for many years,” Buhl-Mortensen said.

Using underwater video cameras, the researchers observed trawl tracks at depths ranging from 160 to 900 meters. But the most affected depths were between 200 and 400 meters, where Buhl-Mortensen said bottom trawls were used in more than half of the sites surveyed.

“We counted up to 62 trawl marks at the locations we studied. So there was only three metres between marks in the places with the highest number of them,” Buhl-Mortensen explains.

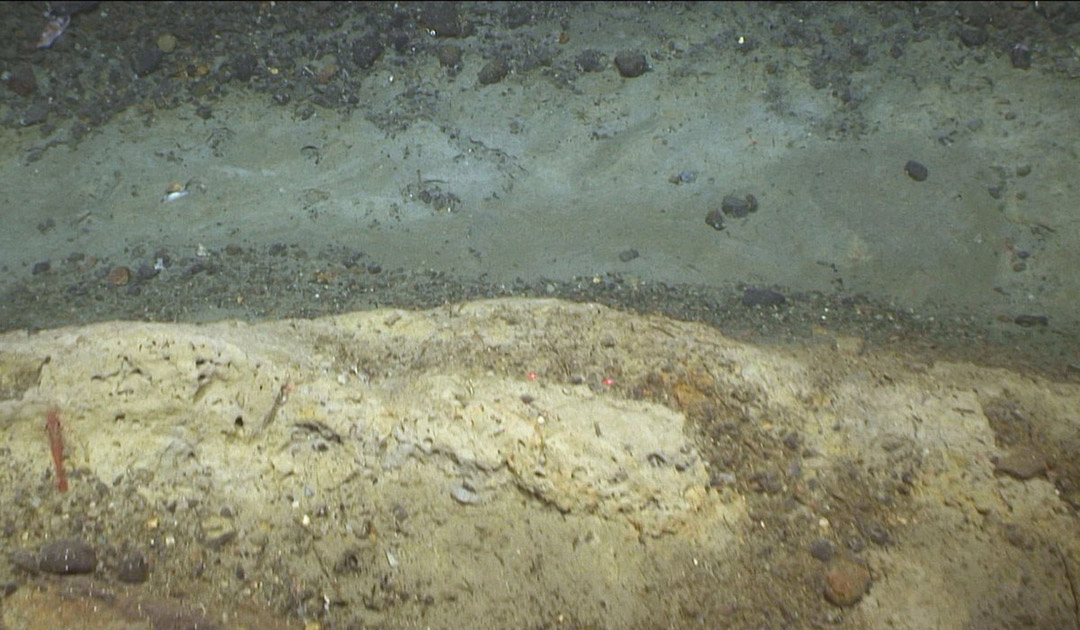

Bottom trawls virtually plow through the seafloor, leaving deep furrows, especially the two doors used to spread the net. The nets themselves are equipped with heavy chains at the opening, which flush out the seabed dwellers. In addition, to prevent damage from stones, so-called dolly ropes are attached to the bottom of the nets, but they often come off, contributing enormously to plastic pollution. It is not uncommon for entire nets to be lost, remaining in the ocean as so-called ghost nets and posing a great danger to marine life.

The seafloor is home to numerous species, now endangered, for which trawling is a major problem. “For instance, this area has quite a lot of Umbellula sea pens, pigtail corals and bamboo corals. These species are considered vulnerable internationally. They are very vulnerable to external impacts and cannot cope with being trawled over,” Buhl- Mortensen explains. “We observed bamboo coral skeletons at four locations, and at two of them there were also living colonies. At one location (770 metres below sea level), there were clear signs of bottom trawling. There we only found dead skeletons.”

During the expeditions, the research team also observed intense fishing activity, with Buhl-Mortensen saying they saw trawlers from many EU member states, as well as Russian and Norwegian ones.

Julia Hager, PolarJournal

More on the subject: