In the deep sea it is pitch dark, cold and food is scarce. And yet, amazing communities of life exist on the seafloor at depths of several thousand meters. In the Weddell Sea, for example, they consist of eelpouts, starfish, sea urchins, and psyllids. They are all waiting for a dead whale, penguin or fish to sink into the depths for them to pounce on. A GEOMAR-led research team has now documented the scavenging community in the northwestern Weddell Sea for the first time using more than 8,000 underwater images.

A regular flow of nutrients enters the deep sea only through so-called “marine snow,” which consists of excreta and remains of marine animals and plants. A veritable rain of particles thus feeds numerous filter feeders, larvae and other marine life throughout the water column down to the seafloor. But the comparatively large eelpouts or echinoderms (sea urchins and starfish) require more substantial food than marine snow. And this comes in the shape of carcasses from the ocean surface and water layers below, yet as irregularly as spatially scattered. Therefore, scavengers have the ability to go for long periods without food. But when food suddenly falls to the seafloor, their keen sense of smell guides them to the meal.

It is not easy for researchers to study the “food falls” and the organisms that benefit from them because they can be anywhere and nowhere. You just happen to be in the right place at the right time with the appropriate equipment. While the so-called “Whale Falls” in the northern hemisphere are quite well studied, little is known about the food falls in the southern hemisphere.

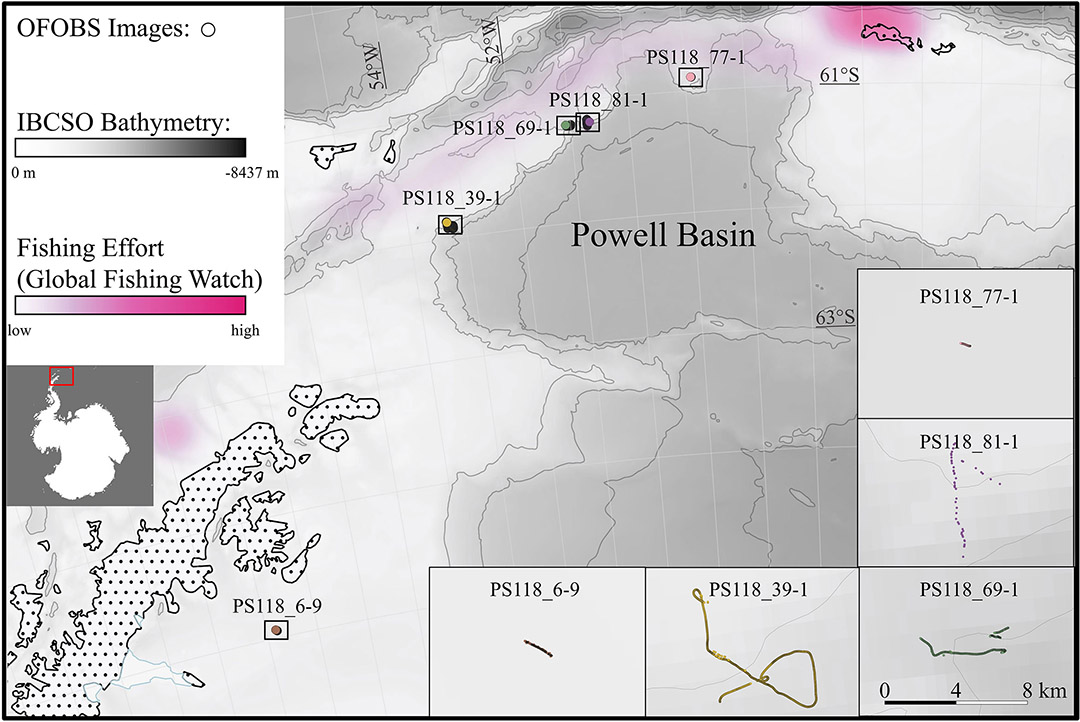

Therefore, the research team specifically set out to find carcasses in the deep sea in the northwestern Weddell Sea. During a 2019 expedition aboard the German research icebreaker Polarstern, scientists used the Ocean Floor Observation and Bathymetry System (OFOBS) camera system to take 8,476 images of the seafloor at depths between 400 and 2,200 meters.

The images revealed carcasses of a baleen whale, a penguin and four fish that were being feasted upon by various scavengers. Never before have such images of dead penguins and fish been taken. According to the researchers, the whale carcass, of which only individual bones and no tissue parts were left, had been lying on the seabed for at least five months, possibly much longer. The penguin, which may have fallen victim to a leopard seal, and one of the fish were largely skeletonized. Sea urchins, brittle stars, and starfish gnawed the last remnants from the penguin’s bones, and on and around the fish, presumably an icefish, at least eleven eelpouts had gathered.

The other three fish, which were still quite fresh, are probably grenadier fish. The authors suspect that they ended up in the net as bycatch during fishing and were thrown back into the sea. On one of the fresh fish carcasses, the researchers discovered amphipods.

Unlike dead whales, smaller carcasses are utilized by scavengers within hours to weeks. Attracted by the intense smell, predatory fish often join them, which in turn target the scavengers.

Like marine snow, food falls are an important component of the biological carbon pump: many different biological processes ensure that carbon is transported from the atmosphere and land to the deep sea. There it is remineralized and made available again as a nutrient for plant organisms or stored in sediments for millions of years.

Fisheries activity, the authors note, interferes with the biological pump in two ways. On the one hand, large numbers of fish are taken that do not die naturally and would contribute to the biological pump as a food fall. On the other hand, fisheries contribute excessively at points by discarding a lot of bycatch.

Julia Hager, PolarJournal

More on the subject: