Antarctic krill is one of the most abundant species on our planet. However, its total biomass can vary greatly from year to year, which can affect how well its predators thrive. Such a correlation is now reported in a new study led by researchers at the University of California Santa Cruz and published in the journal Global Change Biology. They found that good krill availability leads to more pregnant female humpback whales. Conversely, they observed far fewer pregnancies among humpback whales in poor krill years. The new findings could have implications for industrial krill fisheries in Antarctica.

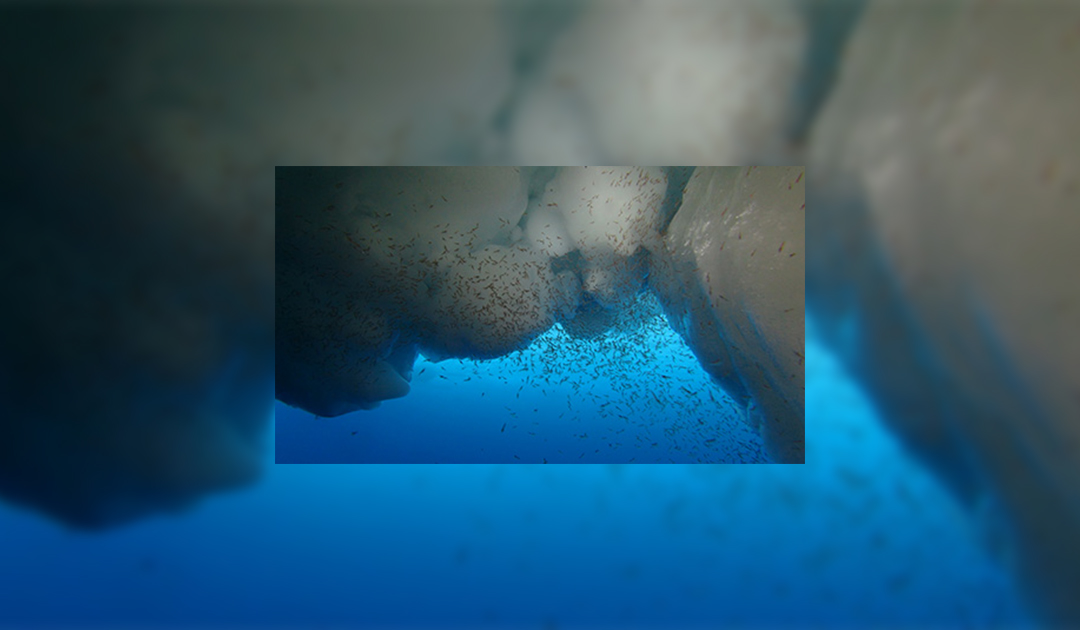

Southern Hemisphere humpback whales spend the summer in Antarctica to replenish their fat reserves. Especially for females, a good availability of krill is crucial, as they need a lot of energy for the upcoming pregnancy.

The international research team studied humpback whale pregnancies over an eight-year period (2013 – 2020) in waters west of the Antarctic Peninsula – a region where krill fisheries are concentrated. They found that in 2017, when krill were abundant, 86 percent of the female humpback whales studied were pregnant. In contrast, only 29 percent of female humpback whales were pregnant in 2020, when krill were less abundant.

The study shows for the first time the relationship between population growth and krill availability in Antarctic whales, said Logan Pallin, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Ocean Sciences at UC Santa Cruz and lead author of the study.

“This is significant because until now, it was thought that krill were essentially an unlimited food source for whales in the Antarctic,” Pallin says. “Continued warming and increased fishing along the Western Antarctic Peninsula, which continue to reduce krill stocks, will likely impact this humpback whale population and other krill predators in the region.”

“This information is critical as we can now be proactive about managing how, when, and how much krill is taken from the Antarctic Peninsula,” he adds. “In years of poor krill recruitment, we should not compound this by removing krill from critical foraging areas for baleen whales.”

According to Ari Friedlaender, professor of ocean sciences at UC Santa Cruz and co-author of the study, annual sea ice extent is on average 80 days shorter than it was 40 years ago. “Krill supplies vary depending on the amount of sea ice because juvenile krill feed on algae growing on sea ice and also rely on the ice for shelter,” Friedlaender said. “In years with less sea ice in the winter, fewer juvenile krill survive to the following year. The impacts of climate change and likely the krill fishery are contributing to a decrease in humpback whale reproductive rates in years with less krill available for whales.”

The research shows that extremely precautionary management measures are needed to protect all Antarctic marine species that depend on krill for survival, including blue, fin, humpback, minke and southern right whales, as well as seals, fish, squid, penguins and other seabirds, says WWF’s Chris Johnson, co-author of the study.

“Krill are not an inexhaustible resource, and there is a growing overlap between industrial krill fishing and whales feeding at the same time,” Johnson explains. “Humpback whales feed in the Antarctic for a handful of months a year to fuel their annual energetic needs for migration that spans thousands of kilometers. We need to tread carefully and protect this unique part of the world, which will benefit whales across their entire range.”

Julia Hager, PolarJournal

More on the subject: