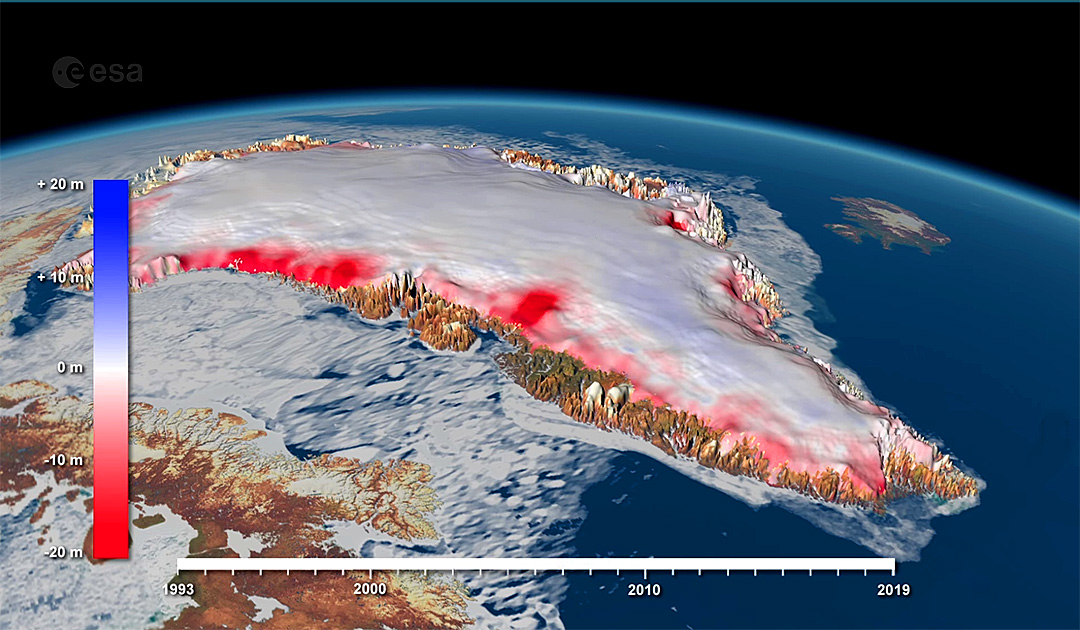

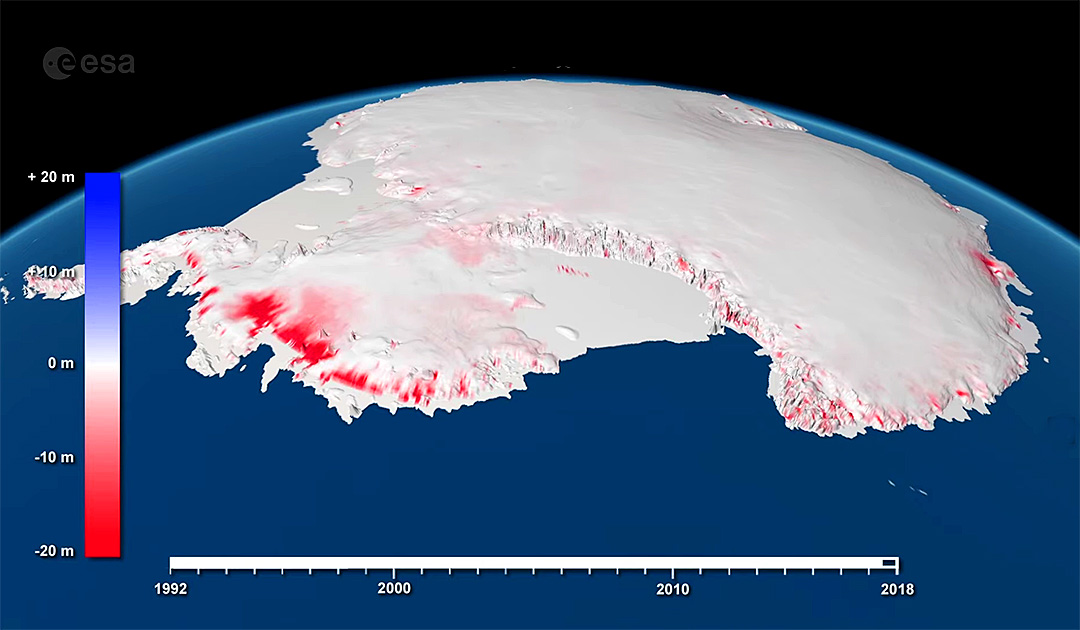

Ice loss from Greenland and Antarctica has increased five-fold since the 1990s, and now accounts for a quarter of sea-level rise, according to a European Space Agency report released on 20 April, that concludes that climate change is causing polar ice sheets to melt, in the process driving up sea levels and putting coastal regions around the world at risk. Since 1992, when satellite records of ice-sheet melt began, the polar ice sheets have lost ice every single year. The highest rates of melt have occurred in the past decade.

Scientists use data from satellites such as ESA’s CryoSat and the EU’s Copernicus Sentinel-1 to measure changes in ice volume and flow, as well as satellites that provide information about gravity, to work out how much ice is being lost.

A team of scientists is compiling these records as part of the Ice Sheet Mass Balance Intercomparison Exercise (IMBIE), funded by ESA and Nasa, America’s space agency. These data are widely used, including by the UN International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to understand and respond to the climate crisis.

The latest IMBIE assessment, released last month, states that between 1992 and 2020, the polar ice sheets lost 7,560 billion tonnes of ice, equivalent to an ice cube measuring 20km each side.

The polar ice sheets have together lost ice in every year since continuous satellite observations began in 1979, with the seven biggest annual declines coming in the past decade.

Melting peaked in 2019, when the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets shrunk by a staggering 612 billion tons.

This was driven by the summer heat wave in the Arctic, which led to a record 444 billion tons of ice being lost from Greenland that year. Antarctica lost 168 billion tons of ice, the sixth most on record, owing to the continued acceleration of glaciers in West Antarctica and record melting from the Antarctic Peninsula. The East Antarctic Ice Sheet remained close to a state of balance, as it has throughout the satellite era.

The melting of the polar ice sheets has caused a 21 mm rise in global sea level since 1992.

Ice loss from Greenland is responsible for almost two-thirds (13.5mm) of this rise; ice loss from Antarctica is responsible for the rest.

In the early 1990s, ice-sheet melting accounted for only 5.6% of sea level rise. However. there has been a five-fold increase in melting since then, and it is now now responsible for 25.6% of all sea level rise.

If the ice sheets continue to lose mass at this pace, the IPCC predicts that they will contribute between 148mm and 272mm to global mean sea level by the end of the century.

The ice-loss assessment, the third produced by the IMBIE team, is made possible thanks to continued co-operation between the space agencies and the scientific community.

Over the past few years, ESA and Nasa have launched several satellite missions capable of monitoring the polar regions. The IMBIE project has taken advantage of these to produce regular updates, and, for the first time it is now possible to map polar ice-sheet losses every year.

Andrew Shepherd, of Northumbria University and the founder of IMBIE, said: “After a decade of work, we are finally at the stage where we can continuously update our assessments of ice-sheet mass balance thanks to satellites measuring and monitoring them.”

This third IMBIE assessment involved 68 polar scientists from 41 organisations worldwide using measurements from 17 satellite missions, including, for the first time, from the Grace Follow-On gravity mission.

The assessment will now be updated annually to make sure that the scientific community has the very latest estimates of polar-ice loss. Diego Fernandez , an ESA spokesperson, noted: “This is another milestone in the IMBIE initiative and represents an example of how scientists can co-ordinate efforts to assess the evolution of ice sheets from space, providing unique and timely information on the extent and onset of changes”.

“The new annual assessments represent a step forward in the way IMBIE will help to monitor these critical regions, where we’ve reached a point where abrupt changes can no longer be excluded.”

Mark Drinkwater, of ESA, said: “For over 13 years our CryoSat mission has played a starring role in measuring changes in polar ice.”

“To secure the long-term continuation of radar altimetry ice-elevation and topographic-change records, we are currently developing the Cristal (short for Copernicus Polar Ice and Snow Topography Altimeter) mission, a Copernicus Sentinel Expansion Mission, to enhance and extend the record from CryoSat and earlier heritage missions.”

IMBIE is supported by Nasa and ESA’s Earth Observatory Science for Society programme and Climate Change Initiative, which has contributed long-term satellite observation records to the study. Data on both ice sheets from multiple missions provides a consistent record of change from the 1990s to the present.

Source: ESA

More about this topic