Valentina Veqet, Anadyr, Chukotka AO, Russia. (Fotokredit: Museum Cerny)

When you think of the Arctic, you automatically think of warm clothing. And of course this is vital. But clothing in the Arctic also has to meet other criteria – depending on its use, it has to be windproof and waterproof. Usually, when you think of warm clothing, one immediately thinks of fur. Polar bears, wolves, seals and reindeer (or the wild form known as caribou) are arguably the most important suppliers. Reindeer is the most important supplier of fur in Europe and Asia (Fig. 1), While in North America it is generally the seals.

unknown, St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, USA. (Fotokredit: Museum Cerny)

What is less well known is that warm and even windproof clothing is also made from various birds, for example eider ducks. Even fish skin is used. Probably the most unusual for us Europeans is the use of various marine mammals’ intestinal skin, trachea and esophagus, that are made into waterproof and windproof jackets and can be found from Greenland to Eastern Siberia. One such piece can be found in the collections of Museum Cerny that was commissioned on site in 1967 by a Bern expedition to Alaska. (Fig. 2) Richly decorated with feathers and coloured leather strips, such pieces are worn for ceremonial occasions.

In Bern (more precisely at the Bernese Historical Museum) there is also one of the oldest surviving specimens, which was collected also in what is now called Alaska during James Cook’s third voyage in 1778. The public library in Bern has a leaflet from 1578, which shows one of the earliest images of Inuit from the area of Southwest Greenland or Baffin Island and their clothing, presumably made of seal skin or fur.

Unknown, Greenland. (Fotokredit: Museum Cerny)

In order to prepare the skin of a freshly hunted animal for further processing, it must first be removed and stretched to dry, then cleaned of fat and meat residues. Further processing takes place depending on its intended use. The hides are tanned to make clothing. In the Arctic, primarily, variants of fat tanning are traditionally widespread, along with vegetable tanning. Both forms serve to soften hides and skins so that they can be further processed into clothing and everyday objects. The thickness of the skin differs depending upon the animal. The walrus skin is so thick that it can be split open to make two thinner skins. Walrus skin is used, for example, to make umiaks, (Fig. 3) the large Inuit boats.

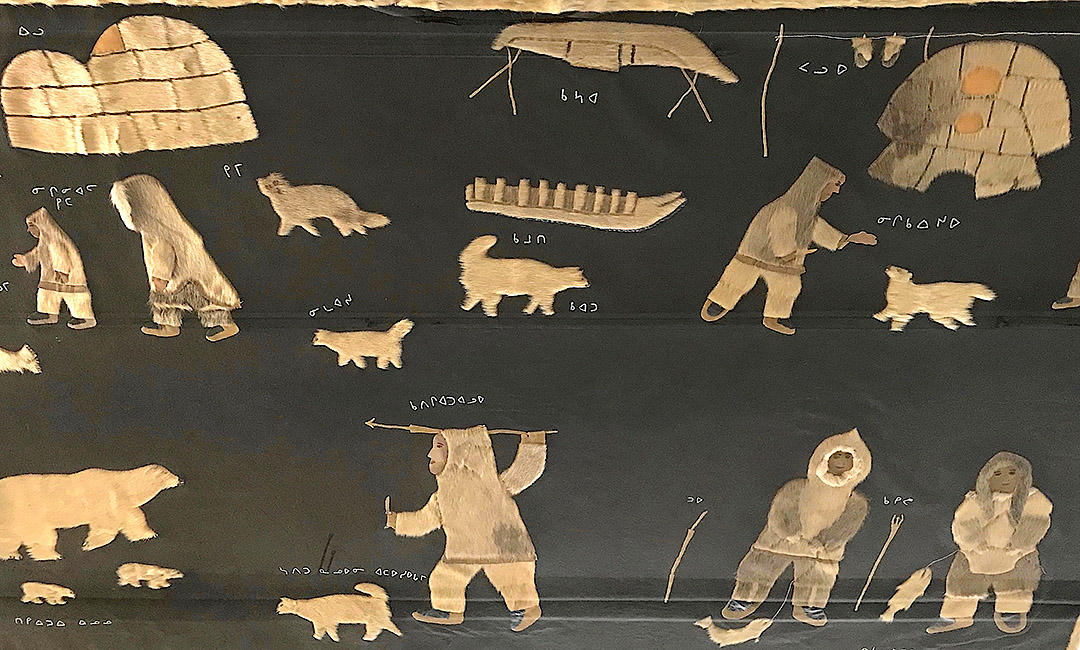

Lucy Ivunirjuk, Arviat, Nunavut, Canada. (Fotokredit: Museum Cerny)

In addition to clothing, tents are made from seal and caribou fur. Organ skins are used, among other things, to make containers, bags and drum skins. Even the skin of some whales was used, for example as the sole for boots. The buoys used to hunt marine mammals were usually made of whole seal skins. Filled with air, they prevent the harpooned animals from diving or, while swimming on the surface of the water, reveal their location to the hunters. Finally, the lines for dog sleds were made from thick rawhide, as were the whips to drive the dog teams.

Lucy Ivunirjuk, Arviat, Nunavut, Canada. (Fotokredit: Museum Cerny)

To this day, hides and skins have hardly lost their importance – but new tanning methods have replaced the old ones and the forms of use have also changed due to new materials. In addition, contemporary art in the Arctic makes use of hides, skins and leather. For example in the forms of wall hangings (Fig. 4) and stencils for prints on paper. The artist, Jesse Tungilik, recently received much international media attention with a spectacular new work currently on view at the Winnipeg Art Gallery – a sealskin spacesuit (https://www.wag.ca/event/inua/) with the Nunavut flag.

There are no limits to innovation and in a constantly changing environment, new ways of using and processing one of the oldest materials known to man are likely to continue to be found.

Martin Schultz, Museum Cerny / Translation by Martha Cerny