We are in the midst of the sixth mass extinction – scientists agree on this in view of the rapid loss of animal and plant species. Mainly habitat destruction and degradation, climate change, pollution, (illegal) hunting and fishing, the spread of diseases and invasive species are made responsible for this. Birds are particularly hard hit: For almost half of all bird species, these threats mean a population decline, as a comprehensive international study on the status of birds worldwide has shown.

The authors of the review study, scientists from several institutions, examined changes in bird biodiversity using data from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) “Red List” to show population changes in the world’s 11,000 bird species. Their results are more than shocking. The authors of the study, published in the journal Annual Review of Environment and Resources, found that about 48 percent of bird species have known or suspected population declines. In 39 percent of the species, populations are stable, and in only six percent are populations growing. The status of the remaining species is unknown.

“We are now witnessing the first signs of a new wave of extinctions of continentally distributed bird species,” says lead author Alexander Lees, senior lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University, United Kingdom, and a research associate at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in Ithaca, New York. “Avian diversity peaks globally in the tropics and it is there that we also find the highest number of threatened species.”

As such, this global study mirrors the findings of a 2019 study that found nearly three billion breeding birds have been lost in the U.S. and Canada over the past 50 years.

“After documenting the loss of nearly 3 billion birds in North America alone, it was dismaying to see the same patterns of population declines and extinction occurring globally,” says co-author and Cornell Lab conservation scientist Ken Rosenberg, now retired. “Because birds are highly visible and sensitive indicators of environmental health, we know their loss signals a much wider loss of biodiversity and threats to human health and well-being.”

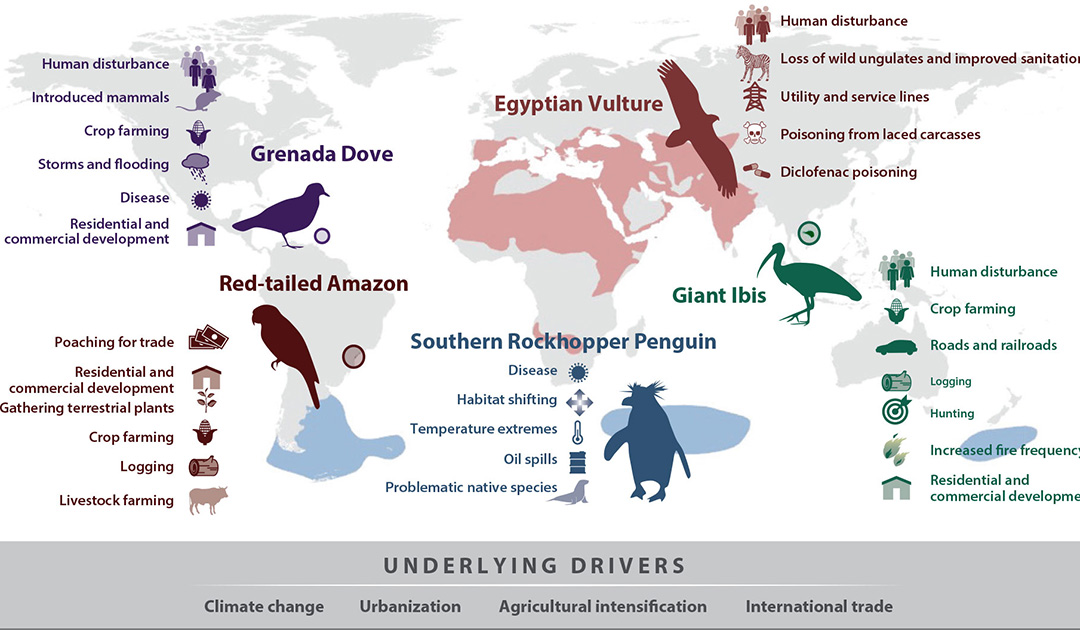

The authors blame various factors as the main causes for the decline of many bird populations:

- Growth of human population with accompanying land use

- Habitat fragmentation and destruction/degradation

- Hunting and trapping

- invasive species

- Disease spread

- increasing demand for “green” energy, especially wind turbines

- Pollution with oil, plastic, pollutants, fertilizers, pesticides, medicines

- Climate change

- Global trade relations, especially for meat, wood, oil seed crops

The effects of climate change are particularly pronounced for migratory bird species that breed in the Arctic. European long-distance migrant birds will probably have to undertake more protracted and longer migrations in the future and thus make additional stopovers. In addition, migratory birds may no longer be able to coordinate their arrival at breeding grounds and the start of reproduction with resource availability. If they return earlier from wintering areas, weather during the earlier breeding period could be unfavorable and result in higher mortality.

One migratory bird species is critically endangered: the spoon-billed sandpiper(Calidris pygmeus). The “Spoonies”, as they are affectionately called, breed only on the coast of the Chukchi Peninsula and the east coast of Kamchatka. They spend the winter in Bangladesh, Thailand, Myanmar, Vietnam and South China. BirdLife International describes in great detail the threats that spoon-billed sandpipers face throughout virtually their entire lives: In their breeding grounds, they suffer from habitat destruction, predators, hunters, bad weather and climate change, resulting in low breeding success. On their journey south, countless animals die because they are still caught or from exhaustion, as they can no longer find enough food at their resting places due to habitat loss. BirdLife International experts fear that there are only about 250 adult spoon-billed sandpipers left in total.

However, there is also good news. Conservation measures, especially the establishment of protected areas, have already helped many species to reverse the negative trend into population growth. These include the black-browed albatross (Thalassarche melanophris), which breeds in the Falkland Islands and South Georgia, and other places. After South Africa, where some of the black-browed albatrosses winter off its coast, introduced measures to reduce bycatch in fisheries, the population decline has stabilized.

“The fate of bird populations is strongly dependent on stopping the loss and degradation of habitats,” Lees says. “That is often driven by demand for resources. We need to better consider how commodity flows can contribute to biodiversity loss and try to reduce the human footprint on the natural world.”

The authors are hopeful that conservation efforts can improve the situation for many bird species, but not without fundamental change. “Fortunately, the global network of bird conservation organizations taking part in this study have the tools to prevent further loss of bird species and abundance,” Rosenberg adds. “From land protection to policies supporting sustainable resource-use, it all depends on the will of governments and of society to live side by side with nature on our shared planet.”

Everyone can contribute to the protection of birds, the authors emphasize. Thanks to easy-to-use apps (e.g., Cornell Lab’s eBird), birdwatchers can report their sightings, filling the database that scientists use to create distribution atlases and population models, which in turn are used to develop conservation measures.

Julia Hager, PolarJournal

More on the subject: