Fin whales are “only” the second largest marine mammals in the world. But that does not make them less fascinating and mysterious. Because our knowledge about their way of life is still incomplete, especially when it comes to their migration routes. Although some work on this has been already published for animals in the Northern Hemisphere, little is yet known in the Southern Hemisphere, especially for populations between the Indian or Pacific Oceans and East Antarctica. An international research team has now changed that and has been able to produce a detailed map for the first time. In the process, they “heard” the routes.

Using more than 800,000 sound recordings made between Australia and East Antarctica within the years 2002 to 2019, the research team with lead author Meghan Aulich, a PhD student at Curtin University in Western Australia, was able to create a detailed map of fin whale migration routes between Australia and Antarctica. This was the first time the researchers were able to demonstrate where the second largest marine mammals in this area of the world go when they undertake their annual migration.

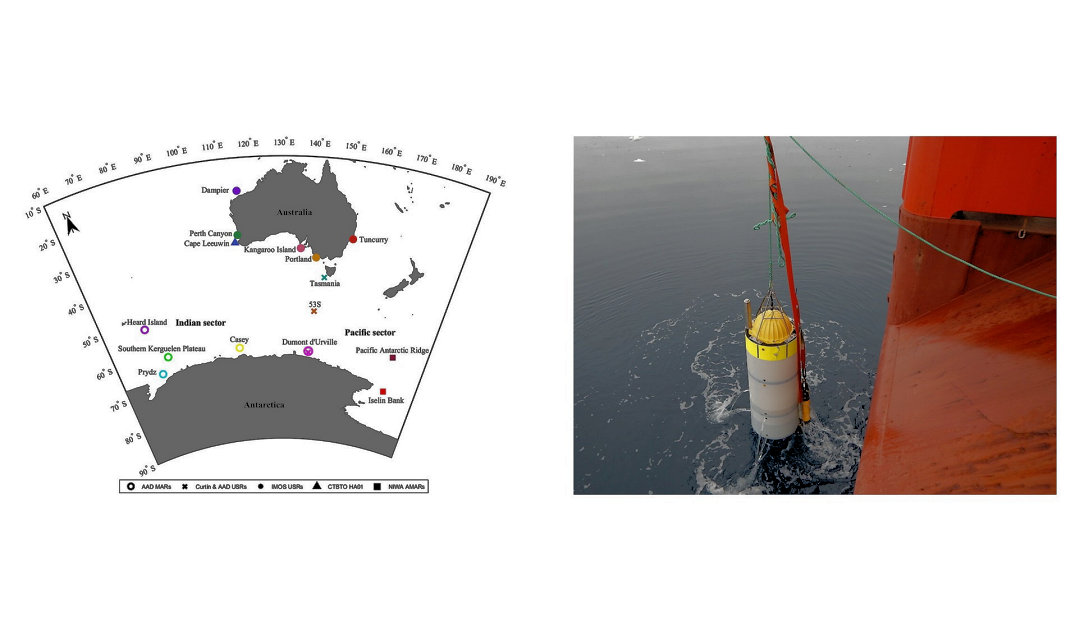

At a total of 15 sites, the Australian Antarctic Division AAD, New Zealand’s National Institute for Water and Atmospheric Research NIWA, Curtin University, and the Australian Integrated Ocean Observing System IMOS had stationed underwater recording devices. Another source of data was a station of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization CTBTO in Western Australia. All of these acoustic stations provided 812,144 recordings of fin whales migrating in regions around Australia and East Antarctica between 2002 and 2019. “By “listening” to the marine world over the past two decades, we have gained new insights into the current distribution and migration of fin whales through the Indian, Pacific and Southern Oceans,” explains Meghan Aulich.

The research team benefited from the fact that fin whales communicate at particularly low frequencies. Classically, these lie between 15 and 30 hertz. However, human ears can perceive underwater sounds only at 500 hertz. Although low-frequency, fin whales are among the loudest animals, with their sounds reaching up to 186 decibels. Thus, sounds can be carried underwater for long distances. This allowed the research team to discover the migratory routes of fin whales between Australia and East Antarctica by passively “listening” to them, and to map their more precise summer and winter residency areas. “We identified two migration pathways, from the Indian Ocean of Antarctica to the west coast of Australia and from the Pacific sector of Antarctica to the east coast of Australia,” says Meghan Aulich about the findings.

The area between the Southern Kerguelen Plateau and the French Antarctic station Dumont d’Urville is particularly popular with whales to spend the Antarctic summer, according to the study. They then migrate back to the west and east coasts of Australia, where they stay between May and October, mating and giving birth to their calves. “From the acoustic information we obtained in this study, we believe there is limited mixing between whales on the eastern and western migration routes, which is preliminary evidence of separate subpopulations between the Indian and Pacific sectors,” explains Meghan Aulich when asked about interactions between the two populations.

The study fills an important gap in southern fin whale conservation efforts. This is because during commercial whaling operations, a total of over 725,000 animals were killed in the Southern Ocean. To date, the southern population has recovered less quickly from this than had been hoped for when the whaling moratorium was established. Experts believe that only about 40,000 fin whales exist in total in southern waters. But there are no reliable figures. For the fast animals often know how to elude the eyes of science in the vastness of the Southern Ocean. Here, however, the study shows that this does not apply to the ears of science.

Dr Michael Wenger, PolarJournal

More on the topic