Many spectacular natural phenomena happen in remote places that are difficult to reach. Off the coast of northern Norway, it’ s also a particularly unfavorable time of year to take a look beneath the water’s surface. During the winter months, masses of orcas and humpback whales migrate into the fjords in pursuit of massive swarms of herring. The big feeding can begin.

The animal that rises in front of me is a true giant. Probably twelve meters long weighing 25 tons. But despite its enormous mass, it pauses almost gracefully above me, then slowly turning to the side and sinking again. If this encounter had taken place in the air, it would probably have been my last hour. But currently being in six meters of water in the North Atlantic Ocean, the mighty humpback whale will not crush me, but gently pass by and disappear again in the deep blue. Through my camera viewfinder I watch the animal vanishing and would like to follow it, but the whale will stay between a depth of 80 and 120 meters in the next few minutes and thus is far beyond my reach. Little comfort remains: I can’t see it – but I can hear it. And not just the one animal that has just passed me, but probably dozens of its fellows and other whale species. All around me there are whistles, squeaks, hums and buzzes, as if I were surrounded by thousands of canaries and quacking ducks in a house with a hundred squeaky doors.

Here, in the depths of the Andfjord between the islands of Vesterålen, a large part of the humpback whale and orca population of the North Atlantic Ocean is feasting. On herring. The huge swarms are found in the fjords around the more northerly city of Tromsø at the beginning of winter and then migrate further south in the following months to head back out into the open ocean after completing their spawning business near the coast. On their journey, they are constantly accompanied by the hungry whales, which are after the herring in the depths, but also drive individual, isolated swarms, so-called bait balls, into shallow bays where they eat them up bit by bit. The wild hunt of the whales has been going on for several weeks this winter. My hunt for captivating images of this wildlife spectacle has just begun.

I work as an underwater cameraman for the German nature film company Nautilusfilm and the Norwegian-based expedition and travel company Northern Explorers, who are working on an elaborate documentary of selected animals of the Norwegian fjord landscape on behalf of NDR Naturfilm. The two-year film project will feature voracious starfish and spawning salmon as well as the giants of the sea in the icy waters north of the Arctic Circle. The working conditions for this part are extremely difficult in January: the sun doesn’t even appear, the twilight around noon allows little light above the waves, and underwater the dim twilight swallows up any shapes after just a few meters. At two o’clock darkness reigns again. But the polar night is drawing to a close, each day becoming visibly brighter, the faint orange behind the snow-covered mountains richer and warmer, the contours of the wave crests sharper. Wind and weather forecasts in these latitudes are to be taken with a grain of salt, mostly we just puzzle over the forecasts for the next 24 hours, which are often far from reality. At minus eight degrees, a storm sweeps over us and large parts of Norway, with the spray whipping over the harbor pier of the town of Andenes, which is covered with a shimmering layer of ice. The bluish glaze is certainly a nice photo motif, but hardly a good sign for efficient work on our ship. The SJØBLOMSTEN (Norwegian for ‘sea flower’) is a former whaling ship and also braves heavy seas, but diving with the whales is out of the question in such conditions. The animals do not mind. While on deck my diving suit, gloves and booties are already frozen stiff, the orcas, well protected with a thick layer of blubber, frolic through the cold waves around our boat, chasing from one side to the other and then disappearing again between the whitecaps.

We decide to sail the SJØBLOMSTEN across the Andfjord to the island of Senja, where some inlets promise better protection with the prevailing wind direction. In the port entrance of Andenes, we are met by high waves that will rock us from one side to the other for the next two hours, jumbling the equipment in the bow and in the hold. Our ship dances over the waves, the cold spray sweeps from the black night over the deck and makes our team doubt the point of our venture. Apparently, only the screeching seagulls are having fun, sailing comfortably in the glow of the deck light. In the shelter of the island, the waves become smaller, the wind dies down, and finally we see the blow of numerous whales off the steep coast.

Hectic bustle replaces lethargic seasickness. Pieces of ice fly in all directions as we open our snow-covered camera cases and I squeeze into my diving suit. Jumping into the four-degree water opens my eyes to a dark world that most people consider hostile, barren and empty. In reality, it is the polar regions that offer a rich supply of nutrients that are home to masses of animals and plants unparalleled on the planet. A tropical coral reef may be motley and diverse in different species. The sheer biomass of a kelp forest off Norway and the immense shoals of fish under our ship surpass it by far. But in the gray water I encounter only a few pollack, cod and herring. This is anything but a large shoal. As I look ahead, I recognize individual white spots just within my range of sight moving towards me. More and more of them appear and a few seconds later twenty orcas pass me effortlessly. Behind them follows the large humpback whale, passing over me and purposefully following the school of orcas. Observations of the animals have shown that often the orcas begin the hunt in a swarm of fish they have spotted and probably attract the nearby humpback whales by their communication sounds. The animals then approach at great speed, dive under the school and rocket upward. It is an unforgettable sight when, during this hunt, the herring jump out of the boiling, churning water in panic and a blink of an eye later the colossus breaks the water surface with its mouth wide open, closes its jaws over several tons of wriggling fish bodies and sinks back beneath the waves. During such encounters, Sven Gust of the Northern Explorers and Jan Haft, founder of Nautilusfilm, are hanging spellbound in front of the underwater microphone, the so-called hydrophone, each of them equipped with one half of the headphones, listening to the wet symphony, the croaking, chirping, whistling and roaring of the marine mammals. The realm in the deep is anything but silent. And anything but barren and empty.

The day ends with successful shots of schools of herring and migrating orcas, which we film both underwater and from the air with a camera drone. It seems that the whales are playing cat and mouse with us. We watch the humpback whales rocketing out of the water at some distance, but as soon as we arrive at the spot, the hunt is already over again, the whales full and withdrawn from our gaze. Only the countless fish scales glittering on the surface indicate that a huge massacre must have taken place here a few moments ago …

The next day I meet Marco von der Schulenburg, a passionate whale expert of the first hour. The following days I spend the few hours with daylight in complete diving equipment lying in a tiny dinghy behind Marco’s boat. As soon as there are enough whales nearby, I try my luck, slide into the water and swim towards the dorsal fins. Every time, the effort to heave myself back into the boat and the disappointment grow when the whales only show up for seconds as bright spots underwater and then vanish. But with animal observations of this magnitude, you obviously get the reward only after prolonged suffering. As we pass a shallow bay close to the cliff on our way back to the harbor, we can hardly believe our eyes: Only a few meters off the gray cliff, we count at least twenty dorsal fins of orcas and humpback whales, which now no longer calmly move, but jump out of the water, throwing themselves twitching from one side to the other and stirring up the water with their flukes. There is no doubt: the big hunt is finally ahead of us. Marco maneuvers his boat closer to shore, and in the shadow of the towering mountains I swim into the underwater darkness. In the next moment, a wall of wriggling fish bodies shoots towards me, reaching from the sandy bottom in ten meters of water to the surface and enclosing me. The massive shoal immediately splits again, revealing the hunter: an orca races towards me, slams its tail fin into the panicked horde of herring, and lets the momentum of its own body slowly whirl it around. The orca somersaults before my eyes – and then calmly plucks the stunned or already shredded herring from the water column with its powerful jaws. The fish try to escape, but are already being rounded up again by other orcas in the group. For the next few minutes I witness the impressive behavior of one of the most intelligent hunters on our planet. The animals cooperate with each other, communicating with clicks and whistles, holding the huge swarm of fish in the shallow water offshore and taking their time to choose the best bite. In this powerful demonstration of nature in the shallow bay, life and death are side by side, here the powerful bodies of the massive orcas circle the pulsating pillars of herring, celebrating a feast amidst half-shredded fish. But the skillful hunters are not the only guests of the richly laid table … – when I surface again to catch my breath, a pressure wave of water, foam and herring overruns me. At the spot right next to me, where there had just been an impenetrable wall of fish, now rolls the grotesquely bloated body of a humpback whale, with thousands of liters of water and certainly as many herrings in its extremely stretchable throat sac. The whale squirms as it presses the water through its baleen, retaining the fish in its mouth. The meat balloon becomes visibly smaller, the herrings enter the whale’s stomach and the freshly fattened animal gets out of my view as the space in front of me fills up with herrings again. After this immediate encounter, it crossed my mind that no human has yet had to figure out how to climb out of a humpback whale again in case you’ve been accidentally swallowed by such a behemoth … In total, I spend more than an hour amidst the chaotic turmoil and only put the camera back in the boat when the darkness underwater no longer allows human eyes to distinguish between herring, humpback whale and orca. Completely exhausted and with cold fingers, I pull myself into the small dinghy while the whale meal continues in front of the grandiose panorama of jagged, snow-covered mountains.

The whales will spend a few more days in Andfjord before following their migratory larder, the massive herring swarms, further south and eventually dispersing back into the Atlantic before beginning their migration again to the rich hunting grounds next winter. For us, impressive images of the hunting animals will remain. And on my diving suit a fine smell of herring.

Text and photos: Uli Kunz

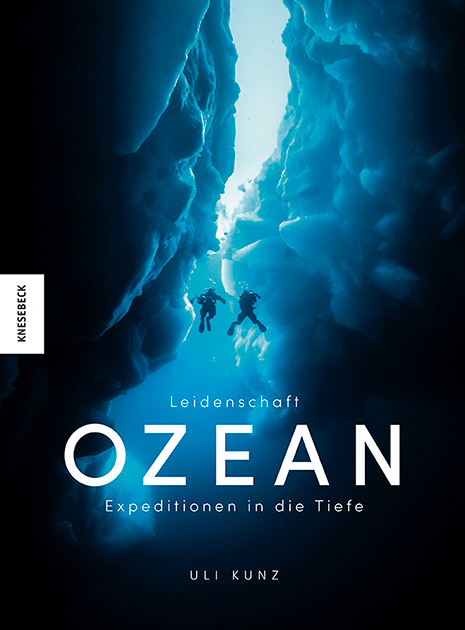

This guest article is an excerpt from Uli Kunz’ latest book «Leidenschaft Ozean – Expeditionen in die Tiefe» (in German only, «Passion Ocean – Expeditions into the Deep»).

Numerous other chapters about his diving expeditions and his passionate commitment to the threatened habitats in the ocean also promise an exciting reading experience.

The book can be ordered on the Knesebeck Verlag website:

https://www.knesebeck-verlag.de/leidenschaft_ozean/t-1/987

Uli Kunz, born in 1975, grew up in Kehl am Rhein in the German state of Baden-Württemberg. As a teenager he got his first diving license and discovered his love for the sea. In 1997 he moved to Kiel to study oceanography. That’ s where he bought his first underwater camera – a second-hand analog Nikonos. He still guards it like a treasure today, even though all his photography has been digital for a long time. Together with four friends, he founded the research diving group Submaris and participates in scientific expeditions around the world. He works for Greenpeace, the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research and the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar Research, among others, examining rocky reefs and marine algae in the North and Baltic Seas, maintaining measuring equipment and diving robots, exploring extensive cave systems and taking photographs under the Arctic ice.

With his live shows he is on tour in German-speaking countries inspiring his audience with fascinating photos and films of the underwater world. With his camera he observes the threatening changes in the ocean and in his projects documents the overfishing of the seas, the destructive impact of climate change on our ecosystems and the increasing pollution of the waters. For the German TV station ZDF, he is in front of the camera as a presenter of the well-known series Terra X, descends to the bottom of a glacier on Spitsbergen, dives in water-filled caves in the Bahamas, photographs the singing humpback whales in the Pacific and lets the viewers participate very closely in one aspect: his fascination for the water.

(Photo: Bjørnar Sævik)

Link to Uli Kunz’ website: https://uli-kunz.com

Follow Uli Kunz on Instagram: @uli_kunz