These are very special French territories, as much for their biodiversity as for their administrative system, whose specific features reflect these “marginal lands at the heart of territorial issues”. An expression borrowed from the conference of the same name organised last October by Florian Aumond, Ludovic Chan-Tung, Anne Choquet and Sabine Lavorel, national and international experts in polar law, who wrote this article on the French Southern and Antarctic Territories. Originally published in The Conversation on the occasion of the One Planet – Polar Summit, we thought it would be useful to remind you of its existence.

France hosted the One Planet – Polar Summit from 8 to 10 November 2023. Among the announcements was the vote on the draft law on polar programming for the years 2024 to 2030, put forward by MPs Jimmy Pahun and Clémence Guetté, co-chairs of the National Assembly’s “Arctic, Antarctic, TAAF and deep ocean” study group. For the first time, this bill “aligns polar research budgets with France’s historic ambitions in these regions”.

The French Southern and Antarctic Lands (TAAF) are at the heart of these ambitions. Made up of five districts – the Crozet archipelago, the Kerguelen Islands, Saint-Paul and Amsterdam, the Éparses Islands and Adélie Land – these territories are nevertheless one of the ultra-marine collectivities that are least well known to the general public. These very specific territories are nonetheless faced with major statutory, geopolitical and environmental challenges.

The ambiguous status of the TAAF

The TAAF have a number of special characteristics, not least their geographical distance from mainland France, the difficulty of accessing them and the absence of a permanent human population. These characteristics explain why these territories are subject to an original form of governance.

The ambiguous status of the TAAFs is set out in a law dated 6 August 1955, supplemented by a decree dated 11 September 2008. The 1955 law described them as an “overseas territory” (TOM), although this legal category was abolished by the constitutional amendment of 28 March 2003, which replaced it with the concept of an “overseas collectivity” (COM). Until now, the legislator has continued to refer to the TAAF as an ‘overseas collectivity’, without really justifying this.

Moreover, it is unlikely that the constitutional reform announced by Emmanuel Macron at the beginning of October concerning the territorial organisation of the Republic, including the overseas territories, will provide an opportunity to clarify this point.

A separate legislative regime

The legal nature of the TAAF is therefore open to question: is it a genuine territorial authority? The answer is tricky: in the absence of a permanent human population, there are no local elections, elected councils or local democracy. Should the TAAF be considered as a special-status collectivity?

This status is all the more special because the TAAFs are governed by the principle of legislative speciality, meaning that French laws do not apply there unless an exception is made. This applies to the Highway Code, the Building Code and the Education Code. This does not mean, however, that the TAAF are not subject to any French regulations since, by way of exception, the Criminal Code, the Civil Code and the rules relating to nationality remain applicable.

It is therefore possible – although rare – for a marriage to be celebrated in the TAAF. In 2014, a French national was fined €10,000 for illegally organising tourist trips to Antarctica and violating the Environmental Code.

Uncertain position and territorial disputes

Unknown, if not unknown, the TAAF are nonetheless connected to major geopolitical issues. They are located on the edge of the Indo-Pacific, which France, following in the footsteps of Japan, the United States, India and Indonesia, has made a central element of its foreign policy.

This new strategic concept updates the approaches that have prevailed until now, placing greater emphasis on the situation of the islands in the zone. Among them, the TAAFs, while constantly mentioned in the discourse, occupy an uncertain position.

They are also the subject of territorial disputes between France and some of its neighbours. The case of Terre Adélie, a ‘sector’ of more than 430,000 km2 located on the east coast of the continent, is a case in point. The Antarctic Treaty of 1ᵉʳ December 1959 in fact ‘froze’ the territorial claims of the seven so-called ‘possessor’ states (Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the United Kingdom), which had the effect of not contesting, but not enshrining, these claims.

The Adelie Islands can therefore remain French from the point of view of Paris, while constituting an “internationalised” area for Washington, Beijing or Moscow.

Îles Éparses, disputed sovereignty

Although France’s claim to the three austral lands (Kerguelen, Saint-Paul and Amsterdam and Crozet) is no longer contested, it is facing two major challenges to its claim to territorial sovereignty over the Éparses islands.

Firstly, Madagascar is disputing the four islands in the Mozambique Channel (Europa, Juan de Nova, Bassas da India and Les Glorieuses). Emmanuel Macron’s visit to the Glorieuses in October 2019, a first for a Head of State, revived the opposition and tightened Tananarive’s stance. Since then, negotiations have stalled.

The same applies to the other territorial dispute concerning the island of Tromelin, between France and Mauritius. However, a co-management framework agreement was adopted on 7 June 2010, organising cooperation between the States on issues relating to research, environmental protection and the management of fisheries resources.

However, it has still not entered into force, as the French Parliament has not authorised ratification. The reasons for this lie in the fears expressed by some members of parliament that it could open a Pandora’s box of loss of sovereignty over these disputed islands.

Biodiversity sanctuary

From an environmental point of view, geographical isolation has largely contributed to preserving the extraordinary biodiversity of the TAAFs as a whole, which serve as a refuge for a large number of protected species. Preserving this unique environment is an increasingly urgent concern, given the impact of human activity and global environmental change.

Here too, the case of Terre Adélie is different from that of the other TAAFs. Its specific environment is protected by a special legal framework, as it is subject to the regulations of the 1959 Antarctic Treaty, in particular the Madrid Protocol and its six annexes. Together, these provide comprehensive protection for the Antarctic environment, and to date have been quite effective in preserving the region’s biodiversity.

In the other TAAFs, the French government has been pursuing a proactive policy of protecting these vulnerable areas for the past twenty years. In 2006, the French Southern Territories Nature Reserve was created around the Crozet archipelago and the Kerguelen, Saint-Paul and Amsterdam islands.

This reserve, which by 2022 will cover an area of 1.6 million km2, is one of the largest marine protected areas in the world and has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2019. Added to this is the 43,000 km2 national nature reserve of the Glorieuses archipelago, whose protection has been stepped up in 2021.

Insufficient protection?

While this move to make natural environments sanctuaries is certainly to be welcomed, it does raise two points.

Firstly, this process may conceal the fact that protection of the marine environment is being exploited in the context of persistent disputes over sovereignty. For example, the creation of the Glorieuses marine protected area in 2021 at the northern entrance to the Mozambique Channel has provoked strong opposition from Madagascar, which has not failed to point out its competing claims to sovereignty over the Éparses islands.

On the other hand, the effectiveness of the protection of protected areas once they have been designated is questionable. The development of management plans to achieve the objectives defined, and the mobilization of resources to achieve these objectives, very often prove inadequate.

Moreover, the establishment of nature reserves does not totally exclude human activities: the TAAF are home to scientific, fishing and tourist activities. While these activities are subject to prior declaration or authorization by the Prefect, administrator of the TAAF, it is crucial to ensure that their impact on this vulnerable environment is strictly limited.

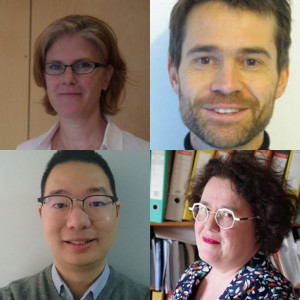

Sabine Lavorel is senior Lecturer in Public Law at Grenoble Alpes University (UGA), and holder of the Ice Memory Law and Governance Chair.

Florian Aumond is Senior Lecturer in Public Law at the University of Poitiers, and Scientific Director of the Colloque – Les terres australes et antarctiques françaises: terres des marges au cœur des enjeux territoriaux.

Ludovic Chan-Tung is a academic lecturer in public law at the Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA), and has contributed to the publication of a book entitled “L’Antarctique : enjeux et perspectives juridiques”.

Anne Choquet is a lawyer specializing in polar space law and a research professor at the Institut Universitaire Européen de la Mer (IUEM) and the Université de Bretagne Occidentale (UBO), President of the Comité National Français des Recherches Arctiques et Antarctiques (CNFRA) and holder of the Chaire Enjeux Polaires.

Learn more about this topic: