Author: William (Bill) Muntean, U.S. Department of State’s Senior Advisor for Antarctica, 2018-2023

The United States is the only major country active in Antarctica that has made no significant policy statement on the region in recent years. All other countries that have significant operations and interests in the region – Argentina (2023), Australia (2022), Chile (2021), China (2017), France (2022), New Zealand (2019), Norway (2015), Russia (2023), and the United Kingdom (2021) – have released policy statements and/or had their head of state/government give high-level policy statements on the region. No senior US government official has recently made any broad statement about its policy towards the region in the past decade nor has the United States updated its policy towards the region that was last updated in 1994!

The silence of the United States about Antarctica calls into question whether it still aims to be active and influential not only in the scientific research that takes place in the region but also in the political fora that maintains the peace and governs where the science takes place. Continued silence by the United States, which traditionally has taken a leadership role in the region since the 1950s, is creating a vacuum that is allowing countries to advance their national interests in the region. There are several inexpensive steps the United States could rapidly take to reduce the risk that other countries will further erode U.S. leadership and interests in Antarctica.

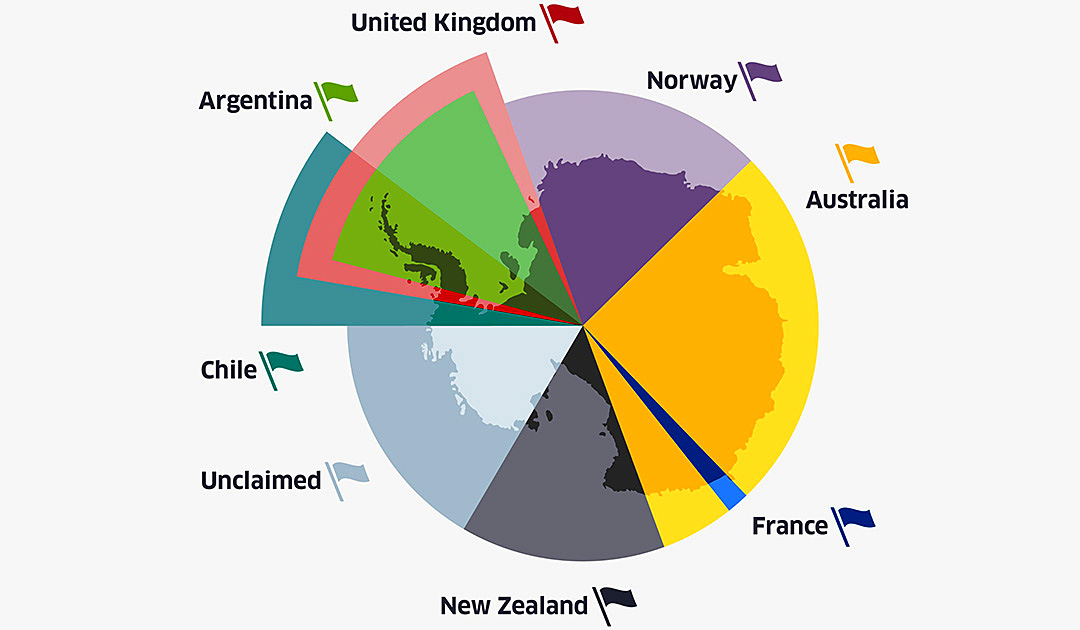

Seven countries (Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom) have announced specific territorial claims in Antarctica, although all of those claims are held in abeyance by the Antarctic Treaty. All of these countries were original signatories to the Antarctic Treaty and continue to actively support it and its related agreements and the United States (and virtually all other countries) do not recognize those claims. Russia maintains a basis of claim over Antarctica and there is periodic concern that China’s activities in Antarctica could lead to a territorial claim, although such a claim is prohibited by the Treaty. Travel by heads of state or government provide an opportunity for public statements as well as drive intra-government information sharing and deliberation about the policy. Releasing an official policy statement also has the same result and process. In the past decade, all of the countries most active in Antarctica except for the United States have either visited the continent or provided a comprehensive policy update about Antarctica.

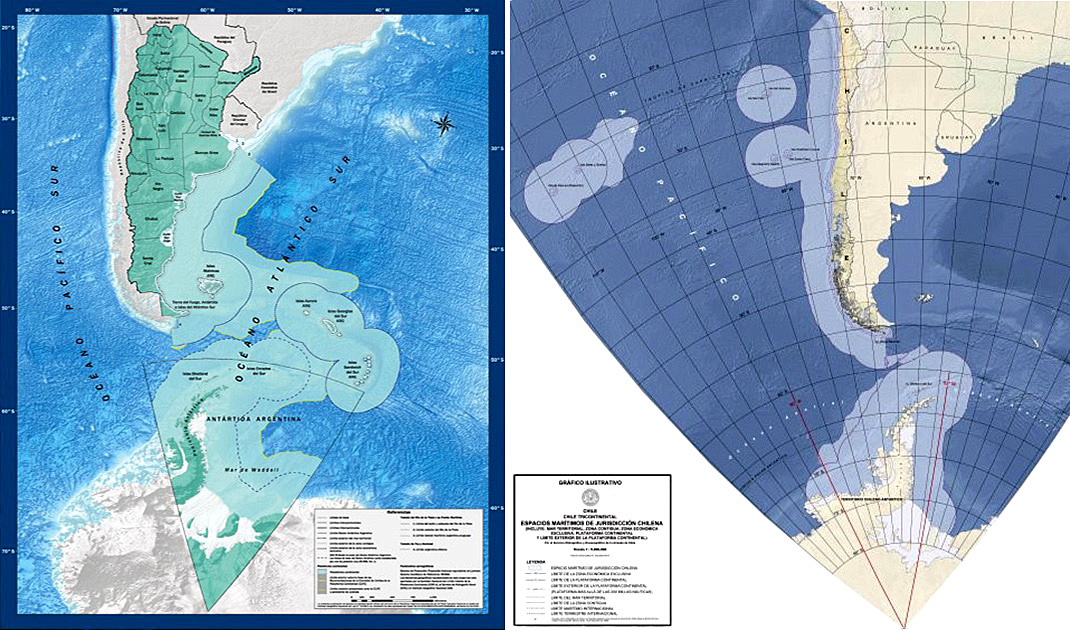

Argentina and Chile were particularly active in 2023 in promoting their Antarctic interests. Argentine President Alberto Fernandez visited Antarctica in February and Chilean President Gabriel Boric visited in June and, again in November, this time with UN Secretary General Gutierrez. Argentine President Fernandez gave a substantive speech during his February visit to say that Argentina’s sovereignty claim over Antarctica was equal to its sovereignty claim over the Malvinas (Falkland) Islands. This builds on his previous Argentine statements about it being a bi-contential country. Chile released its updated Antarctic policy in 2021 that has protecting and promoting its sovereignty in the region as a top priority. Both countries have increasingly publicly highlighted their respective and conflicting claims in the Southern Ocean based on their unrecognized Antarctic territorial claims.

Australia (2022), France (2022), New Zealand (2019), Norway (2015), and the UK (2021) have all recently updated their Antarctic policy. All reinforce their sovereign territorial claim, with Australia and Norway also prioritizing developing economic opportunities related to Antarctica while France emphasized environmental protection. Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison in 2022 also announced a $800 million commitment to focus on strategic objectives in addition to science. Perhaps surprisingly due to their historical roles in Antarctica, neither Australia nor the UK have sent senior government officials to the Continent in recent years. New Zealand’s former Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern visited in October 2022 and Norway’s King Harald V and two ministers traveled to the region in 2015.

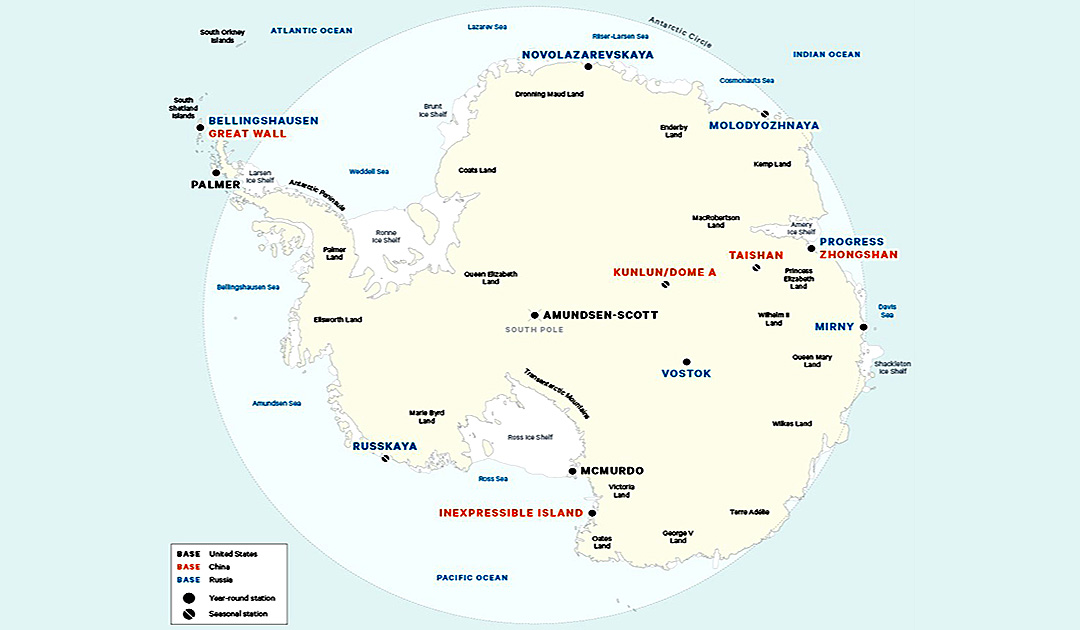

The same as the United States, Russia maintains the basis of a territorial claim but has never said where or under what justification it would make that claim. Russia released its most recent ten-year Antarctic plan in 2021, included Antarctica as a regional priority area in its 2022 Maritime Doctrine, and included it for the first time in its 2023 Foreign Policy Concept. China is the most-active country that does not have a territorial claim or even basis of a claim and is actively increasing its regional presence. It released its White Paper in 2017 in conjunction with it hosting the annual Antarctic Treaty meeting, but has not otherwise provided high-level public policy guidance on the region. With the February 7 2024 opening of Qinling Station, its third year-round station, it is clear that China is actively increasing its footprint in Antarctica. Unlike many of the other countries in this paper but similar to the United States, senior Chinese and Russian government officials have not recently visited the region.

The silence of the United States

The United States has not issued any policy guidance this century, so is still using its 1994 version, nor has any senior U.S. Government official give a speech that sets forth policy guidance towards the region in years. A golden opportunity to provide an overview of U.S. interests was when the United States hosted the annual Antarctic Treaty meeting in 2009, but Secretary of State Clinton instead chose to use her remarks opening that meeting to focus on specific U.S. proposals at that meeting. That same year, the White House sent to Congress legislation to update U.S. law related to Antarctica, but Congress did not take action on the request and there has been no significant push from senior government officials to advance that legislation in recent years.

Secretary of State John Kerry was personally involved in establishing the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area and visited Antarctica in 2016, but did not publicly comment on U.S. interests or priorities in the region beyond that one deliverable. The United States did for the first time ever mention Antarctica in its 2022 National Security Strategy, saying, “And we will promote Antarctica’s status as a continent reserved for peace and science in accordance with the provisions of the Antarctic Treaty of 1959.” However, one line added in what appears to be an afterthought does not provide much guidance to anyone about U.S. priorities and interests in the region, nor has that guidance been explained by other documents released by relevant U.S. government agencies such as the Department of State and National Science Foundation.

Silence is only a problem if the United States does not want claimant countries or strategic competitors to take a leading role in Antarctica. Since the 1950s, the United States has led the balancing between the seven claimants and all other non-claimant countries as well as ensuring the region does not become a platform from which the United States and its allies and friends are threatened. It is unclear at this moment whether these are still a high-level goal of the United States or merely the preference of the technical experts that cover the region.

There are several options should the United States wish to resume being active and influential on Antarctic policy issues. One option would be to update the 1994 policy guidance; reaffirming, if still accurate, that the United States would maintain its position of working collaboratively through the Antarctic Treaty system, that it continues to reject all sovereignty claims over the region, and that it reserves its own rights, could reduce concerns that Antarctica could become as contentious as the Arctic. Another option would be to advance legislation in Congress to implement various instruments the United States has agreed to in annual Antarctic Treaty meetings in 2004, 2005, and 2009; doing so would both advance those specific issues (broadly related to protecting the Antarctic environment) and provide a vehicle for the Executive and Congressional branches to better understand and act on U.S. interests in the region. Another option would be for the Secretary of State to give a speech on the U.S. policy towards Antarctica; while there is no reason for Antarctic-issues to have the same level of prominence as Arctic issues, decades of silence creates a vacuum into which other countries can and are filling.

For good reason, Antarctica is more frequently in the news in the United States for environmental reasons: countries must urgently act to reverse the impact of global climate change on Antarctica, specifically its melting sea ice and threatened ice sheets that are threatening people around the world through potential sea level rise and changing global currents. However, it is useful to recall that relevant environmental tipping points can be best researched in Antarctica if the continent continues to be reserved for peace and science. Increased questions about politics and peace raises doubts about scientific investments at a time when countries should be redoubling their efforts to understand the anthropomorphic effect on our world.

The opinions and characterizations in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. government.

William (Bill) Muntean is a Senior Associate (non-resident) at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), where he focuses on Antarctic geopolitics. He was a career Foreign Service Officer with the U.S. Department of State for over 22 years. His final diplomatic assignment was as the Senior Advisor for Antarctica, overseeing a range of political, economic, and environmental & scientific activities related to Antarctica, from August 2018 to July 2023. In this position, he was the deputy U.S. representative to the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting twice and was the U.S. Head of Delegation in 2022 (Berlin) and 2023 (Helsinki). He also led the 2020 U.S. inspection team, which conducted unannounced inspections of three Ross Sea stations, including the PRC station under construction on Inexpressible Island that is now called Qinling Station (see picture).

More on the subject

USAP and interventions of US at ATCMs have always had great impact on scientific research and the proceedings of the Treaty meetings respectively.

Hopefully the protection of Antarctic environment and it’s wilderness will weigh high in any future policy release from US.

Tough to protect the environment when the deep pockets and lobbyists for the astrophysics community have a “burn baby burn” attitude on expansion in remote locations on the continent. The more stuff the world builds in Antarctica, the worse off the world is for pollution and climate change.