The retreat of sea ice in the Arctic raises many questions: When will the Arctic be ice-free? What does the loss of ice mean on a large and small scale? Will primary production increase as a result? What about sea ice drift? Three new studies have looked at these questions.

Ice-free Arctic in the next 10 years

The day when the Arctic can be described as ‘ice-free’ for the first time could come within the next ten years, regardless of the emissions scenario, researchers from the University of Colorado Boulder report in a review article published on 5 March in Nature Reviews Earth & Environment.

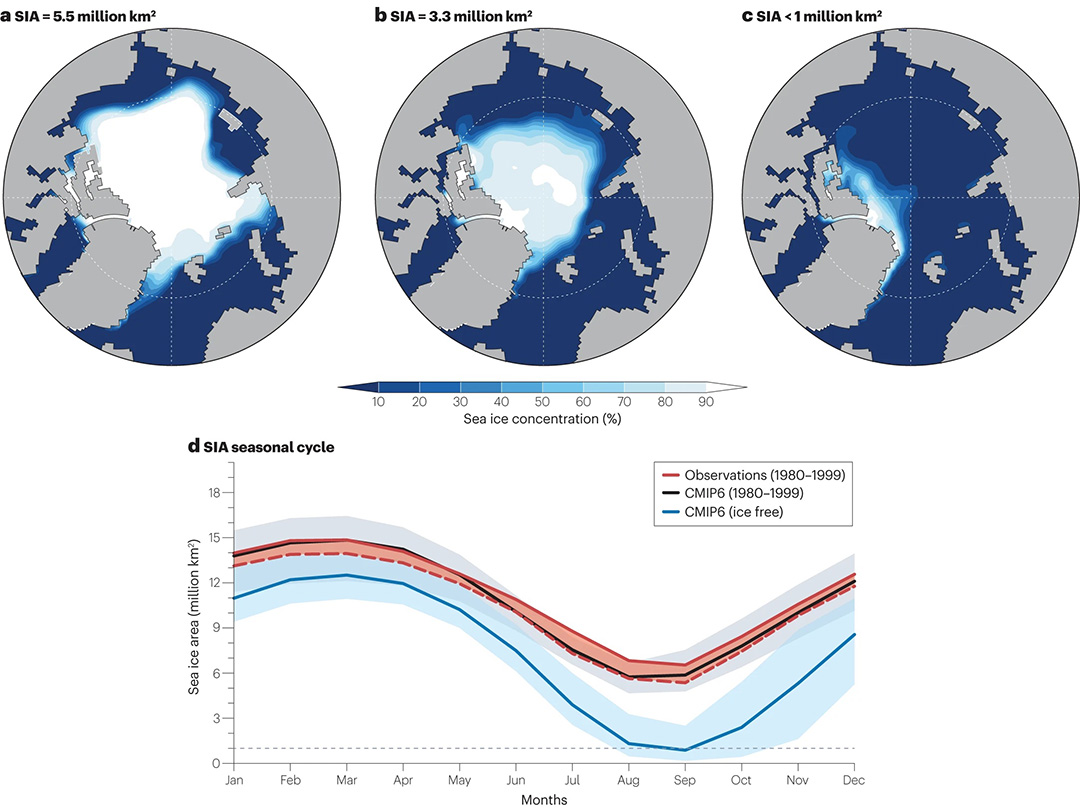

But what does ‘ice-free’ mean? In climate research, the Arctic is said to be ‘ice-free’ when less than 1 million square kilometres of sea ice covers the ocean. According to the team, this will happen for the first time on a day in late August or early September between the 2020s and 2030s.

Under both a high and intermediate emissions scenario, we need to prepare for consistent ice-free conditions towards the middle of the century, which could last from August to October or, in the worst case, nine months, the study says. These would occur first in the shelf seas of the European Arctic, then on the Pacific side and finally in the central Arctic. If, on the other hand, we succeed in emitting significantly fewer greenhouse gases, an ice-free Arctic could remain the exception.

The authors conclude by emphasising that the effects of an ice-free Arctic Ocean on marine ecosystems, the global energy balance, wave height and coastal erosion urgently need to be researched.

Sea ice concentration in the 1980s at 5.5 million square kilometers (a), from 2015 – 2023 with 3.3 million square kilometers (b) and with less than 1 million square kilometers in an ‘ice-free’ Arctic (c). The graph shows the seasonal sea ice cycle from 1980 – 1999 (d). Figure: Jahn et al. 2024

Does less sea ice mean more sunlight on the Arctic seafloor?

There are already initial findings on the effects of sea ice retreat on primary production on the seafloor in the shallow, coastal regions of the Arctic Ocean. In a study published on 4 March in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, an international research team led by Professor Karl Attard from the University of Southern Denmark estimates that the contribution of microalgae, macroalgae and seagrass growing on the seafloor is about one third of the total annual primary production in the Arctic. The team estimates that the production of benthic primary producers is four times greater than that of sea ice algae, but it has received less attention.

Contrary to expectations, the decline in sea ice and the increase in seafloor area exposed to sunlight (about 47,000 square kilometers added annually since 2003) is leading to an increase in benthic plants and productivity along Greenland’s and Canada’s coasts only. It is decreasing on a large part of the Russian continental shelf. The team of authors blames the turbidity of the water due to sediment input from rivers for the reduced primary production, as less sunlight penetrates to the seafloor.

“Our study suggests that the impacts of climate change on sunlight availability and primary production in the Arctic Ocean are complex. Additionally, as the Arctic Ocean continues to warm, we may witness more species migrating from lower latitudes, potentially leading to a more productive marine environment than what exists today—at the cost of losing what is special for the Arctic,” Professor Attard said.

Common seaweed (Zostera marina) could spread in the Arctic as conditions become more favorable, providing new habitat for juvenile fish and other organisms. It also binds large quantities of carbon dioxide. Photo: Claude Nozères via iNaturalist

The speed of sea ice drift could decrease again

Also on March 5, the scientific journal The Cryosphere published a study by York University on the speed of Arctic sea ice, which has been increasing for decades and making shipping more dangerous. Climate models, on the other hand, assume a future slowdown in sea ice drift, especially in summer. However, the causes and timing of the predicted change are not yet fully understood. In addition to wind and the tilt of the sea surface, the internal tension of the ice may also play a role, explained Neil Tandon, Associate Professor at York University’s Lassonde School of Engineering: “As the thinner sea ice expands and contracts more, it generates more momentum for the sea ice, just like one of those spring-loaded toy cars goes faster the farther back you pull it.” The slowdown could occur towards the end of the century or much earlier. For shipping, slower drift ice would increase safety again, but the long-term decline in sea ice remains a concern for ecosystems, indigenous communities and the global climate, Professor Tandon said.

Photo: Michael Wenger

Julia Hager, PolarJournal

Links to the studies:

More about this topic: