On South Georgia, invasive plants and invertebrates colonise the newly available habitats in front of the melting glaciers relatively quickly – which probably does not bode well for the native flora and fauna.

Climate change and the loss of biodiversity are closely linked, which is evident worldwide, for example, in the spread of invasive species due to global warming. Invasive species have also long been a problem on the sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia. While some have now been eradicated, others are becoming increasingly established. Many of them were introduced by whalers and sealers in the 19th and 20th centuries. With warming, the conditions for these species are apparently becoming increasingly favourable – on the one hand due to a more favourable climate and on the other hand due to more available habitat as glaciers recede.

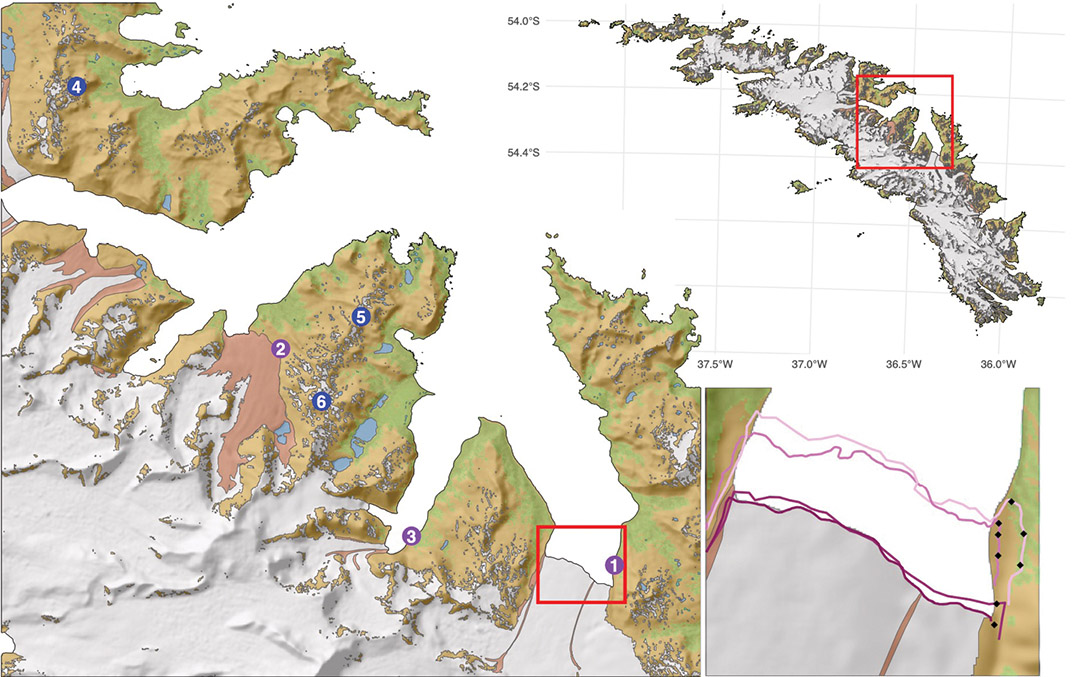

In April 2022 and January/February 2023, a research team from the UK and the Falkland Islands documented in detail the flora and invertebrate fauna that colonize the foreland of the glaciers in various stages after their retreat.

In the study, which was published in the journal NeoBiota on 28 March 2024, the team reports on plant communities near six glaciers that consist predominantly of native species: 18 species near the tidewater glaciers and seven species at an altitude of around 400 meters near the inland cirque glaciers. However, two of the four invasive species observed in particular – common mouse-ear (Cerastium fontanum) near the tidewater glaciers and annual meadow grass (Poa annua) near the cirque glaciers – are almost as common as the native alpine timothy (Phleum alpinum), which is most frequently found near both types of glacier. Invasive plant species also include the common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale), which the team observed only rarely.

Native species also dominated among the invertebrates, although the researchers discovered only five native species and no invasive species near the cirque glaciers. Near the tidewater glaciers, on the other hand, they found 16 native species and five invasive ones, of which a ground beetle species (Merizodus soledadinus) was the most common.

In general, the team found that the first pioneer species colonize only a few years after the ice retreats, spreading more and more over time before the number of species increases. Among the invasive plants, the researchers primarily identified the two common species of common mouse-ear and annual meadow grass as pioneers, both of which originate from the northern hemisphere. Among the invasive invertebrates, ground beetles and springtails are among the first on the new ground.

According to the study, the invasive species do not yet appear to pose too much competition for the native species. However, the authors argue that the situation may change as warming progresses, to the benefit of the introduced plants. The negative effects of the spread of invasive species on native species and the unique ecosystem still need to be investigated in future studies.

Julia Hager, PolarJournal

More about this topic: