The Paris climate agreement calls for everything to be done to limit global warming to 1.5 or a maximum of 2 degrees Celsius. The most important measure to achieve these goals is considered to be the drastic reduction of carbon emissions worldwide, which alone is an immense challenge. Countries are therefore examining how much greenhouse gas can still be emitted without exceeding temperature targets. A team of scientists at the University of Washington has now studied how emissions of other substances and compounds, such as soot or nitrogen oxide, affect temperature increases. They found that including all emissions shortens the time to reach the Paris climate goals.

In the new study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, the team, led by the University of Washington, calculated how much warming we can definitely expect based on past emissions. Unlike previous research, the current study includes emissions of shorter-lived greenhouse gases such as methane and nitrogen oxide, as well as aerosols such as sulfur and soot, in addition to carbon dioxide emissions.

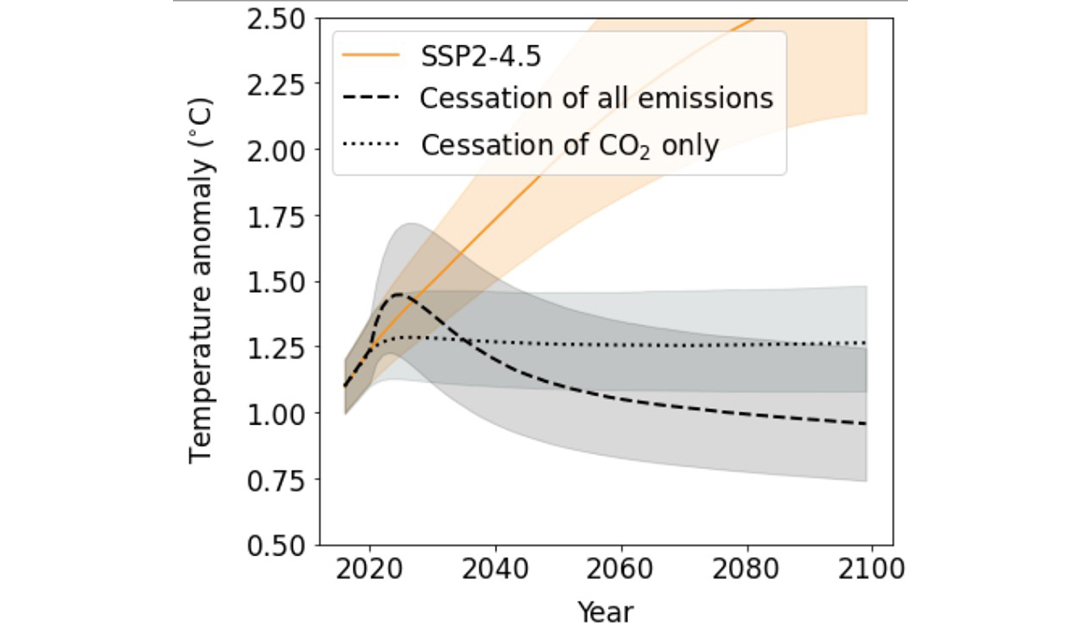

Using a climate model for eight different emission paths, the scientists examined how the Earth’s temperature would develop if all emissions were suddenly stopped in each year from 2021 to 2080. They found that under a moderate emissions scenario, there is a two-thirds probability that warming will exceed 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2029, at least temporarily, even if all emissions are stopped by then. If emissions remain at a moderate level, there is a two-thirds chance that global warming will exceed 2 degrees Celsius, at least temporarily, by 2057.

“It’s important for us to look at how much future global warming can be avoided by our actions and policies, and how much warming is inevitable because of past emissions,” said Michelle Dvorak, a doctoral student in oceanography at the University of Washington and lead author of the study. “I think that hasn’t been clearly disentangled before – how much future warming will occur just based on what we’ve already emitted.”

Previous studies that considered only carbon dioxide emissions found that there was little or no warming after emissions were stopped.

Depending on the type of emissions, there is a warming or a cooling effect. Particles (soot, etc.) in the atmosphere reflect sunlight and thus have a cooling effect, but are quickly removed from the atmosphere, while the long-lived greenhouse gases store heat. If all anthropogenic emissions were stopped simultaneously, the Earth would warm abruptly but temporarily – for a period of about 10 to 20 years – by 0.2 degrees Celsius once emissions cease.

“This paper looks at the temporary warming that can’t be avoided, and that’s important if you think about components of the climate system that respond quickly to global temperature changes, including Arctic sea ice, extreme events such as heat waves or floods, and many ecosystems,” said Kyle Armour, associate professor of atmospheric science and oceanography at the University of Washington and co-author of the study. “Our study found that in all cases, we are committed by past emissions to reaching peak temperatures about five to 10 years before we experience them.”

If we are to meet the Paris climate agreement’s goal of limiting warming to below 2 degrees Celsius, the authors say our remaining “carbon budget” is much smaller than previously thought.

“Our findings make it all the more pressing that we need to rapidly reduce emissions,” Dvorak said.

Julia Hager, PolarJournal