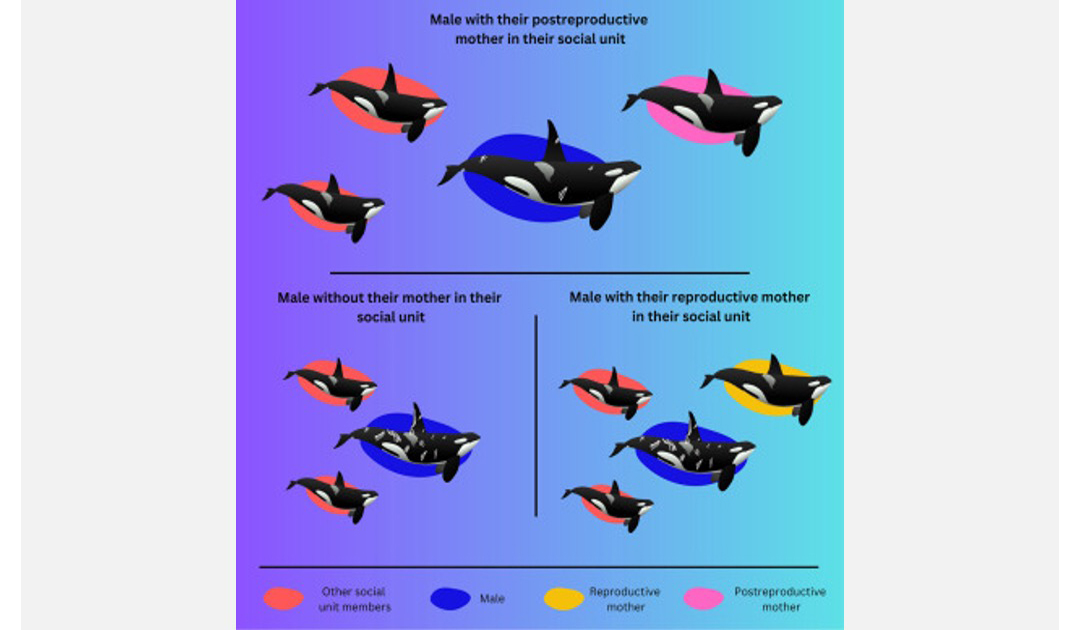

Postmenopausal female orcas are very protective of their sons, to the point of avoiding aggressive social interactions within the pod. On the other hand, daughters and grandchildren do not benefit from this maternal protective treatment.

Nearly 7,000 photographs of 103 southern resident orcas (Orcinus orca) spanning 50 years of demographic records form the database used in a study recently published in Current Biology to reach the conclusion that post-menopausal orcas reduce social injury to their male offspring. This is the result at least for the Southern Resident Orca population, a genetically distinct ecotype whose main habitat during the summer months is the coastal waters of Washington State (USA) and British Columbia (Canada). Some seventy individuals make up this particular population, comprising three pods.

This protection seems to apply only to their male offspring, as post-reproductive female orcas do not appear to protect their daughters, grandchildren or other young members of their social unit. “The same effect is not observed in females, demonstrating that social support is directed towards male offspring and may be a key way in which post-reproductive females help their relatives,” notes Charli Grimes, ethologist at the University of Exeter and lead author of the paper.

To date, the phenomenon of menopause has only been identified in six species. Humans and five species of toothed whales, including orcas. Generally considered to be reproductive between 12 and 40 years old, any female above her forties is considered postreproductive. The average female lifespan for southern-resident ecotype orcas is about 50 years, but with individuals that can reach 60 or 70 years old. Therefore, such female orcas can expect to live more than 20 years after menopause has started, giving them a lot of time to take care of their male offspring.

Why protecting their son…

The discovery made by the research team raises the question of the role of social support in the evolution of menopause in orcas. “For a prolonged post-reproductive lifespan to evolve, there must be a pathway by which post-reproductive females can help their loved ones.” And that pathway could involve increasing the survival chances and reproductive success of their adult sons.

Male orcas, protected in this way by their mothers, can benefit in many ways from this social support, such as food sharing or protection from aggressive interactions with other pod members. Fewer bites mean fewer wounds, and therefore a lower risk of developing infections, particularly fungal types, which can prove fatal for the animal.

However, females do not appear to use force to protect their offspring. They even seem to steer clear of physical confrontations, as indicated by the few wounds on their bodies: “Post-reproductive females show the lowest incidence of raking of any age class, potentially reflecting a lack of direct physical involvement in the conflict”, note the authors.

…but not their daughters ?

Why is support directed towards sons rather than daughters? “This pattern of maternal care can be explained by the theory of kinship dynamics, which predicts that females should preferentially direct their helping behavior toward their sons.” In other words, when a female mates outside the group, the calf is raised within her pod, which represents a cost to the pod. Conversely, a male who breeds in another social group does not place this burden on his group.

Another advantage of protecting a male offspring is that the latter will reproduce more than a female, thus transmitting more genes, to several partners of different pods.

As the current study only surveyed orcas of the northwest Pacific, it will be interesting to see whether other orca pods in the Northern and Southern hemisphere show a similar behavior.

Mirjana Binggeli, PolarJournal

Link to the research : Grimes et al., Postreproductive female orcas reduce socially inflicted injuries in their male offspring, Current Biology (2023), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.06.039

More on the subject