The popular saying ” Things used to be better” is unlikely to be true, at least when it comes to environmental pollution. After all, research findings show that humans have been heavily polluting their environment since ancient times. A new study now shows that the spread of toxic heavy metals had already taken on global dimensions in the Middle Ages and reached as far as into the heart of Antarctica.

Study leader Dr. Jospeh McConnell from the Desert Research Institute in Nevada (USA) and his international team of colleagues from Austria, Germany, Norway and the USA looked back around 2,000 years into the past when they examined five ice cores from East Antarctica. For the first time, the team focused on six toxic and non-toxic heavy metals (lead, cadmium, thallium, bismuth, cerium and sulphur) that are transported around the globe through the air. The goalwas to find out whether global pollution by heavy metals is a product of the modern age or whether it had already occurred in the past.

The results clearly show the course of humanity’s industrial history around Antarctica. The team found significant lead deposits from as early as the 13th century and the deposition of the other heavy metals investigated (except thallium) to an increasing extent over time up to the 20th century.

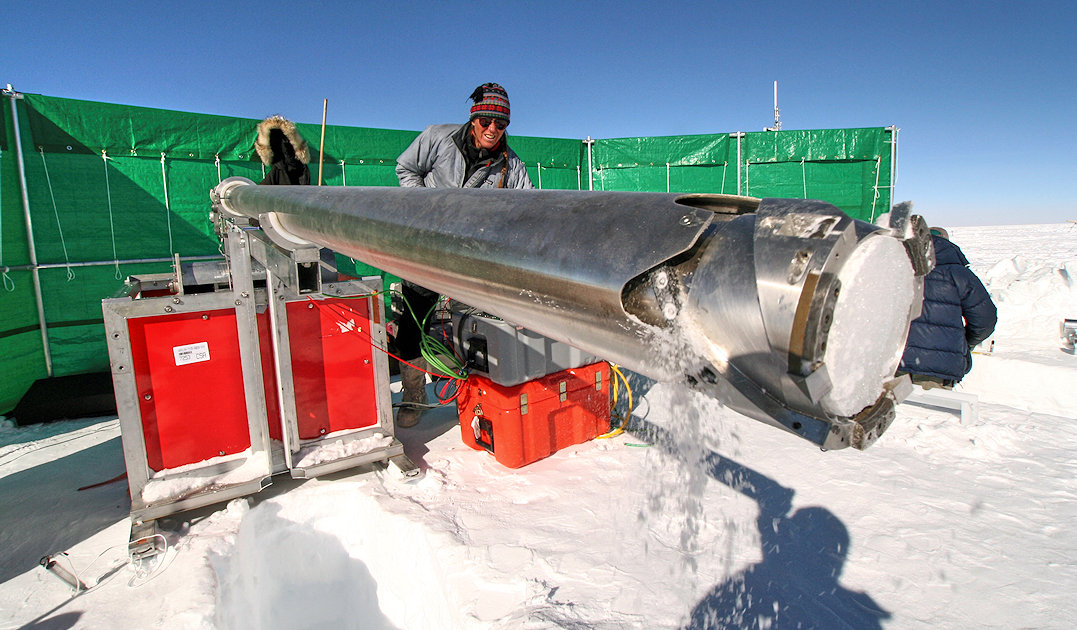

McConnell and his team found the deposits of the various heavy metals in ice cores taken from various locations during a Norwegian-US-American crossing of East Antarctica. According to the team, no liquids were used that could have contaminated the samples. Afterwards, the drill cores were transported by plane and stored.

In the end, longitudinal thin sections were analyzed at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, Nevada (USA). “We’re arguably the only research group in the world that routinely makes these kinds of very detailed measurements, especially in Antarctic ice where concentrations of these trace metals are extremely low,” explains DRI assistant professor and co-author of the study Dr. Nathan Chellman.

The team was also able to separate the heavy metal isotopes that end up in the Antarctic ice from the Earth’s crust and volcanic activity from the heavy metals emitted by human activity. To this end, they used the thallium concentrations, which had not changed in the ice even in the course of industrialization and could only be explained by volcanism.

The results of the research team show a clear progression of heavy metal deposits that correlates with the course of mining history, first in South America and then, starting at the end of the 19th century, in Australia. Of these six heavy metals, the team discovered five in the ice cores (lead, cadmium, bismuth, cerium and sulphur), initially in small quantities. Nevertheless: “Seeing evidence that early Andean cultures 800 years ago, and later Spanish Colonial mining and metallurgy, appear to have caused detectable lead pollution 9,000 km away in Antarctica is quite surprising,,” says Dr. McConnell. The scientists found a stronger increase with higher concentrations later in history, when mining activities were intensified from the late 19th century onwards. “We found that lead, bismuth and cadmium levels increased by an order of magnitude or more after industrialization,” McConnell adds.

In the process, they were able to create a fairly accurate picture of human history and also trace various global events and their influence on the transport of heavy metals to Antarctica. Events such as the plague outbreaks, the two world wars and the Great Depression led to significant declines in the deposits. “It’s pretty amazing to think that a 16th century epidemic in Bolivia altered pollution in Antarctica and throughout the Southern Hemisphere,” says Dr. Sophia Wensman, PhD, DRI researcher and co-author of the study.

Overall, the results of the research group show that the ice of Antarctica is not only an important climate archive, but also a reflection of human history. On the other hand, they also show that our activities have not only had a global impact since the 20th century.

Dr Michael Wenger, PolarJournal

More about this topic