The Mendel Polar Station was opened after wishes from scientists but has since become important for national interest. Czechia, the newest member of the Antarctic community, has its own reasons for conducting polar research.

“From the very start, it was a bottom-up approach. It started as an initiative from the scientists themselves who wanted to work in Antarctica. So, it was us who had to go to the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports, and convince them it was a good idea,” Pavel Kapler, Chief of Operations at the Czech Antarctic Research Programme, told Polar Journal.

He’s sitting in an office with high ceilings and a bookshelf full of polar writings at the Masaryk University in Brno, Czechia. Although he will not be going this year, his thick neck warmer and the confidence with which he talks about Antarctica, reveals that he is not unfamiliar with the southern continent. And indeed, over lunch, he discloses that he has been there 10 times already.

But he is not the most senior polar explorer in the room. Across from him behind a wide desk, sits his boss and the occupant of the office, Daniel Nývelt. He is the Head of the Programme and has been to Antarctica 11 times.

On this day in January, during the austral summer, they are the only two Antarctic scientists left in Brno. The rest of the programme, more than 20 Czech scientists, have travelled south.

“In some other countries, South American countries in the 1970s for instance, their presence in Antarctica began for political reasons. They wanted to colonize the continent. But for us it was only about science. We wanted our own station so we could conduct long-term and continuous research,” Daniel Nývelt said.

“Changed the direction of my life”

Czech polar research began in the 1980s with the professor Pavel Prošek. Back then, while the country was still called Czechoslovakia and was under communist rule, he and other researchers from the Masaryk University travelled to Svalbard where they collaborated with Soviet and Polish expeditions.

After the Velvet Revolution in 1989, when they could suddenly collaborate with other countries, Pavel Prošek and his colleagues started to travel south to Antarctica as well, working with Peru, Ukraine, Poland and others. But they were always part of other expeditions, relying on others for accommodation and support.

Pavel Prošek wanted more.

“When Pavel told me he wanted to build our own station in Antarctica, I thought: ‘splendid idea, I must be there’,” Daniel Nývelt recalled: “It was a challenge, of course, but it was a challenge I wanted to be a part of, and one that gave my life a new direction.”

Pavel Prošek, who had the idea, is 84 years old today and a professor emeritus at Masaryk University. It was him, too, who, around the year 2000, managed to convince the Czech government to fund the country’s very own Antarctic station.

The deglaciated James Ross Island

Then came the question of where to place the new station. At first, the idea was to build it at the South Shetland Islands, at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, but the other Antarctic countries, the signatories of the Antarctic Treaty, did not like this idea.

“They told us that if we wanted to continue research at the South Shetland Islands, we should just use other facilities. There are enough stations built there already,” Nývelt said.

Instead, the Czech scientist set out to find a better, less researched location for their station. And not too far South, they found such a place. The James Ross Island had no other stations on it, and the nearest station was 80 kilometres away.

And moreover, the island was scientifically interesting as it is one of the areas in Antarctica that has been ‘deglaciated’ the longest. During summers the snow melts away, so, for the past 600 years, some species of lichen and moss have grown there.

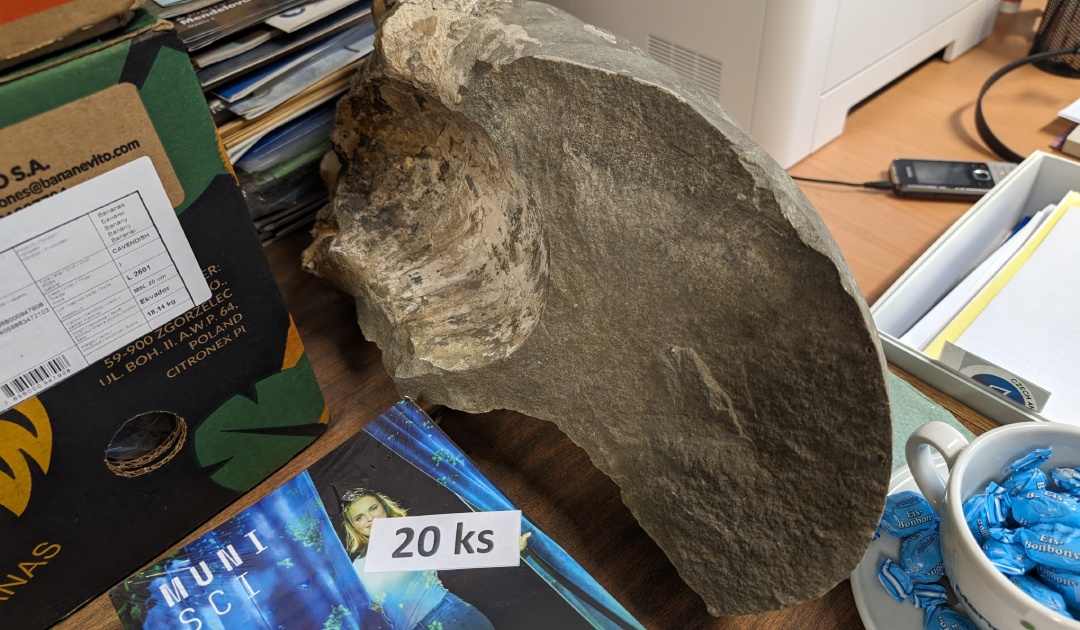

And that is just one of many things that made James Ross Island worth researching. Others include rapidly melting local glaciers, the fossils of sponges, and layers of freshwater expanding the sea ice.

Follow Polar Journal next week, for more on the science conducted at James Ross Island.

Convinced the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

In 2004, the first Czechs set foot on the island, sleeping in tents and starting work on the establishment of the new base. The work took two summers, and the base opened in 2007.

All of the sudden, Czechia was an Antarctic country, eligible for inclusion in Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCM), the forum where Antarctic matters are discussed.

In 2012, the scientists at Masaryk University began to push the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs to seize this opportunity. With some reluctance they did, so in 2014 Czechia became the latest of the 29 countries with a so-called consultative status in the Antarctic Treaty.

Slowly, the Czech government began to see strategic reasons for its presence in the far south.

“Before the consultative status, there were no long term plans, but today it is included in The Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ foreign policy strategy. They use it to gain a voice in Antarctic matters,” Pavel Kaplar said.

“They also told us that Czechia’s status and level of bilateral cooperations within the EU grew importantly after gaining the consultative status. From the viewpoint of the EU, it shows that we feel responsibility not only for ourselves but for the entire planet. So our Antarctic base also helped our politicians,” Daniel Nývelt added.

Gregor Mendel, the meteorologist

The Johann Gregor Mendel Station, as the Czech base in Antarctica was named, is now operating in its 18th year. It has helped Czech researchers make important contributions to science, and it is always looking to help other countries.

“We are always open for collaborations. That is really the Antarctic spirit,” Daniel Nývelt said.

That leaves just one question to ask in this Antarctic enclave in the middle of Brno: How did the station get its name?

The first reason is obvious. Johann Gregor Mendel, the world-famous father of modern genetics, was a native of Brno where Masaryk University is located. “His abbey is just three tram stops away,” Pavel Kaplar said, pointing out the window.

However, aside from the few mosses and lichen that grow there and the sea animals that come and go, James Ross Island is not exactly ideal for the study of genetics. But genetics was not the reason for the naming, Daniel Nývelt explained.

“Gregor Mendel was a founding member of the Austrian Meteorological Society and he put a lot of effort and money into constructing the network of meteorological stations around Moravia (the Czech region where Brno is located). So, for us he was a meteorologist, not a geneticist,” he said.

In the years after the fall of communism in Czechia, when Mendel and genetics had been unpopular, people in Brno were eager to honor their forgotten hero. As a result, his name was, perhaps, used a bit too eagerly.

“It is confusing for some journalists that the Mendel Polar Station is connected to Masaryk University, not to Mendel University, our neighbors. We have to correct that often,” Pavel Kaplar said, laughing.

Ole Ellekrog, PolarJournal

More on the subject