The scientific team of the SWAIS 2C project has successfully completed the first stage and recovered the first sediment cores. However, there were technical problems with the drilling under the ice sheet, which will only be solved next season.

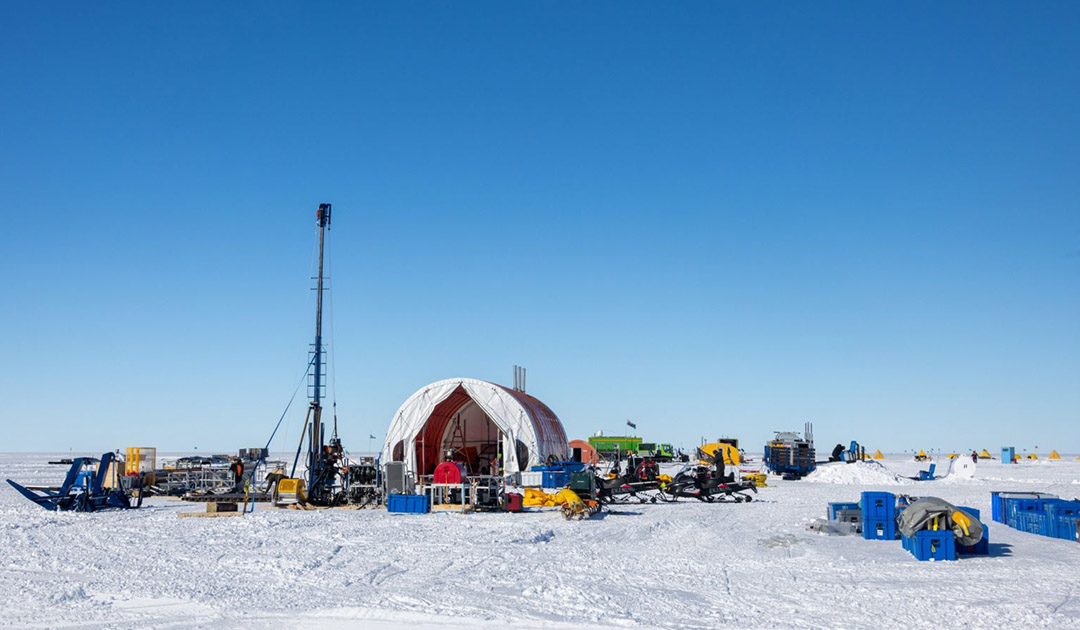

The international research drilling project “Sensitivity of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to Two Degrees of Warming” (SWAIS 2C), which also involves the German Alfred Wegener Institute, has achieved an important success: The researchers and drilling experts succeeded in drilling through the 580 metre thick Kamb Ice Shelf with a hot water drill and extracting a total of ten sediment cores from the sea floor below. One of the cores is almost two metres long – the longest ever taken from the remote Siple Coast.

“We’re at the frontier, drilling through an ice shelf into the seafloor, to acquire sediment samples that no one has previously been able to obtain. It’s cutting-edge science and incredibly challenging work,” Professor Richard Levy, co-chief scientist of the project from GNS Science Te Pū Ao and Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, says in a university press release.

Unfortunately, the researchers’ hopes of being able to drill around 200 metres deep into the seabed were not fulfilled this time. Technical problems stopped the drilling close to the goal and forced the team to end the drilling for this season and recover the equipment. However, the scientists are confident about the coming season, as only simple modifications to the drilling system need to be made.

The team hopes that the sediment samples will provide important insights into the history of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet: “The sequence of rocks in the sediment should tell us how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet behaved when it was a bit warmer than today—if we find marine algae it’s likely the ice sheet retreated. This information will allow us to build a much better picture of how Antarctic ice will respond to future warming, which parts will melt first, and which parts will remain,” Professor Levy explains.

The coveted core is said to date back hundreds of thousands of years, possibly even millions of years, and thus depict the last interglacial period 125,000 years ago, when the Earth was around 1.5 °C warmer than before industrialization, i.e. similar to the temperatures we will reach due to climate change.

The researchers hope that the deep sediments will provide information on whether the Ross Ice Shelf and the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could melt if global average temperatures at the Earth’s surface are 2 °C higher than before the Industrial Revolution.

However, it is not only the sediments that are of interest to the researchers, but also the water between the ice shelf and the sea floor. Using a CTD probe, which measures the salinity, temperature and density of the water, they collected important oceanographic data. A long-term mooring equipped with a series of instruments also collects data over several years on ocean currents and properties in the area of the grounding line where the ice shelf rests on the continent. These observations will help researchers to understand how the warming of the Southern Ocean affects the temperature of the water under the ice shelf, which can increase melting along the grounding line.

Even though the project goal was not fully achieved this season, the team is extremely happy: “We are thrilled with what we’ve achieved, it’s a massive step forward towards our ultimate goal to recover the sediment we need to answer the big questions that are crucial for humanity as we adapt and plan for sea-level rise,” Professor Tina van de Flierdt, co-chief scientist of the project from Imperial College London, says.

Julia Hager, PolarJournal

Link to the project website: https://www.swais2c.aq/

More about this topic: