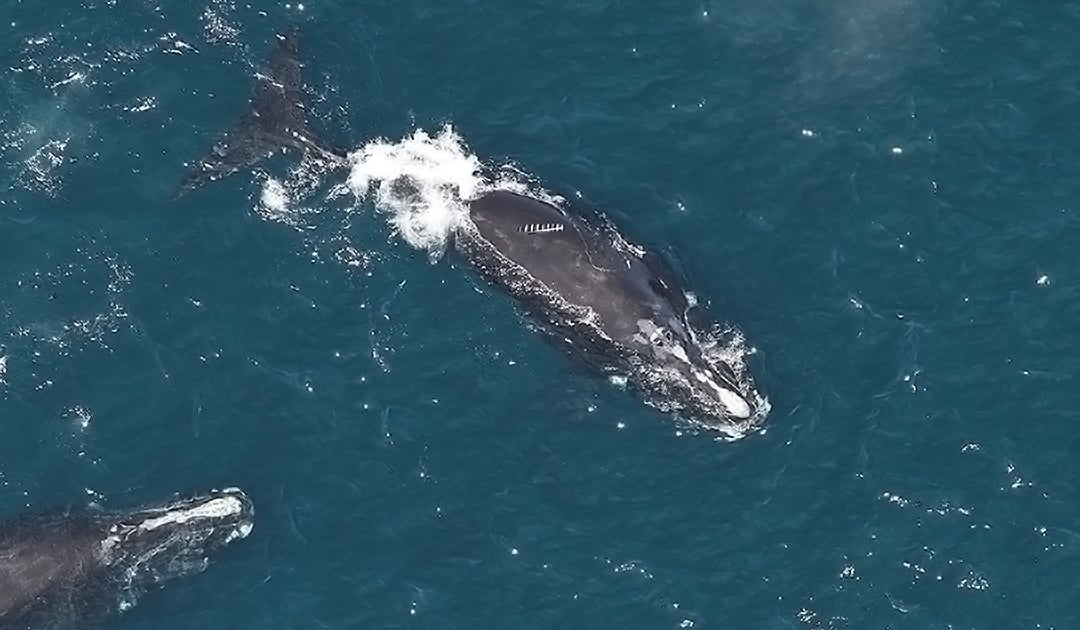

North Atlantic right whales are among the most endangered whale species on our planet. One of the greatest dangers to them is the immense shipping traffic along their migration routes. With the help of artificial intelligence, the danger of collisions is now to be minimized. The Canadian government is investing $5.3 million in five projects as part of the smartWhales initiative to drive the development of innovative solutions that will help detect and monitor whales in Canadian waters and predict their migration routes.

There are three species of right whales worldwide – right whale in the sense of “perfect” or “ideal” whale. The docile right whales were the preferred target of whalers because they swim slowly at the surface when feeding, they usually stay close to shore, and they do not sink after killing because of their thick layer of blubber. These characteristics brought the animals to the brink of extinction. To this day, the two northern species – North Pacific right whale and North Atlantic right whale – have not recovered from the relentless hunt. The eastern population of North Pacific right whales probably has only 30 animals left, and the total population has a few hundred. Things don’t look any better for North Atlantic right whales: According to recent estimates from the

All three species spend summers in high latitudes, where they take advantage of the rich feeding grounds, and winters in temperate latitudes or the subtropics to breed and give birth. Among the greatest dangers on their migrations are ship strikes and entanglement in fishing gear.

A better protection is now in sight at least for North Atlantic right whales during their migrations.

“Counting whales in the open ocean is like finding needles in the proverbial haystack. They may be the largest beasts on the planet, but they are tiny if you have to search at an ocean scale. Developing an AI approach to automatically identify them from satellite imagery will help us to understand their numbers, movements and threats in seas that are ever more crowded and utilised by humanity.”

Dr Peter Fretwell, Wildlife from Space Project Manager at the British Antarctic Survey

The Canadian government launched the smartWhales initiative, led by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), which will fund five projects over the next three years to protect North Atlantic right whales using satellite data, including a project to monitor right whales and their habitat and a project to develop a system that provides near real-time information on the predicted presence of right whales and the potential risk of an encounter with a ship.

Several institutes and organizations, including the British Antarctic Survey, the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, Dalhousie University and the Ocean Frontier Institute, will work together to develop a solution that uses machine learning and high-resolution satellite imagery to detect the whales. The imagery, hosted on the AI-based OCIANA™ platform, can be used to provide warnings and route recommendations to ships to avoid collisions with the whales. As part of the global routing solution, ships will also receive route and speed recommendations when whales are in the area.

OCIANA™ is an AI-based platform from the company Global Spatial Technology Solutions (GSTS) that ingests large amounts of data from a range of satellite and ocean-based sensors that contain information on the ocean, weather, ships, ports and marine life activity.

“This as an opportunity to transform our vision of being a catalyst between meaningful ocean research, and its real-life application in government, industry, and community. Providing information that can be used by decision makers, to make sure that we’re keeping these whales safe, that we’re finding out as much as we can about them, and that we’re doing everything that we can to make sure that all whales survive”, Olivia Pisano said, a PhD student at Dalhousie University.

Hopefully, the initiative will be successful and come in time for the North Atlantic right whales, which are threatened with extinction. Perhaps the solutions can then be applied not only in Canadian waters and also to other whale species.

Julia Hager, PolarJournal

More on the subject: