The study analyzed data across the Southern Ocean from 2006 until 2021. Its results are great news for a species that was almost entirely wiped out by whaling.

Since time immemorial, blue whales have been an evasive species; hiding away in remote reaches of the ocean, far from the watchful and oftentimes predatory eyes of humans.

In 1851, for instance, when the most famous book on whales, Moby-Dick, was published, they were nothing but a myth.

“There are a rabble of uncertain, fugitive, half-fabulous whales, which, as an American whaleman, I know by reputation, but not personally,” Herman Melville, author of the classic novel, wrote then, before he named the mythical-sounding beasts whose existence he was uncertain of:

“The Bottle-Nose Whale; the Junk Whale; the Pudding-Headed Whale; the Cape Whale; the Leading Whale; the Cannon Whale; the Scragg Whale; the Coppered Whale; the Elephant Whale; the Iceberg Whale; the Quog Whale; the Blue Whale.”

Indeed, blue whales, though they turned out to be real, have always been difficult to track. Like the whalers of old, present day scientists struggle to locate them, and thus to keep track of their numbers.

But a study by a group of scientists under the Australian Antarctic Division have employed a new, more effective method of tracking them. And its results are positive: the number of Antarctic Blue Whales appears to be at least stable, and possibly increasing.

Whale songs or whale calls

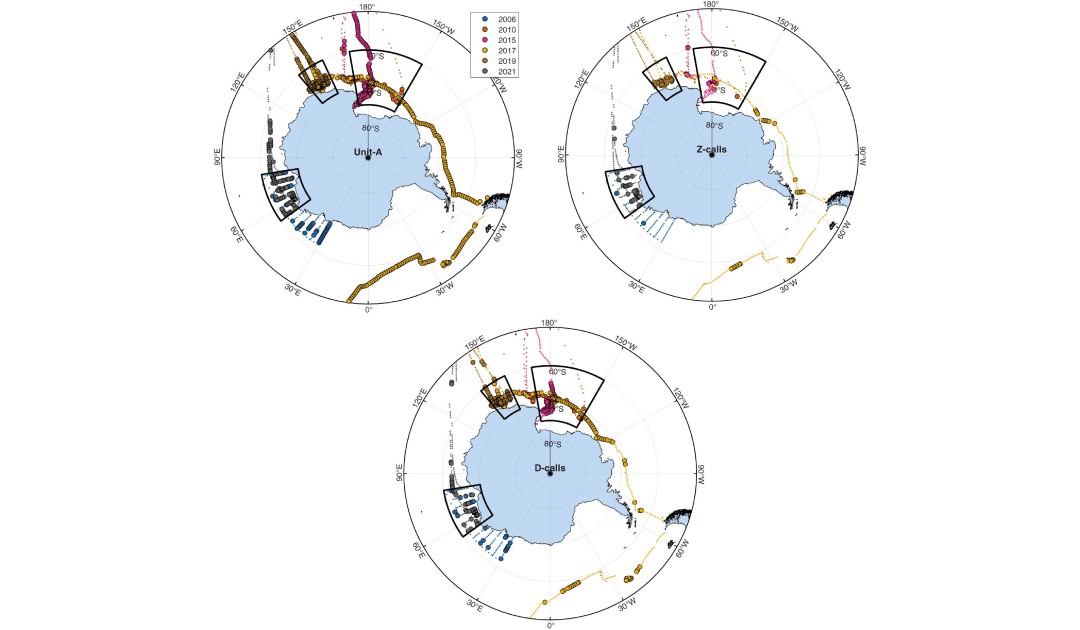

The study analyzed data from so-called sonobuoys left in the Southern Ocean from 2006 until 2021. Through these years, the sonobuoys recorded thousands of hours of audio from locations around Antarctica.

Scattered in these recordings were the songs and calls of blue whales within a radius of thousands of kilometers. The Southern Hemisphere blue whales use the waters around Antarctica as summer feeding grounds, so the sonobuoy recordings provide a good estimate of the overall population of the subspecies.

In the study, researchers divided the calls into three categories: unit-A, D-calls, and Z-calls. Unit-A calls are songs, while D-calls and Z-calls are non-songs of higher and lower pitch respectively. Songs on, on the one hand, are believed to be produced only by males, while non-song calls are difficult to distinguish from those of another nearby subspecies: the pygmy blue whale.

As a consequence, to gain an adequate view, analysis of all three call types are necessary.

According to the researchers, this distinction between call types combined with the vast coverage of space and time, means that the study gives an unprecedented look at the current status of the Southern Hemisphere blue whales.

And it is in these audio recordings that a positive trend can be detected. “The proportion of sonobuoys with presence of these three call types was predominantly higher in more recent surveys,” the study stated.

Increase in number or detection

Although the study is modest in its enthusiasm, its authors are more excitable when they were interviewed about it.

“When you look back to before this work was started by the AAD, we really just had so few encounters with these animals – and now we can produce them on demand,” senior research scientist at the Australian Antarctic Division Brian Miller told the Guardian.

“Either they’re either increasing in number or we’re increasing in our ability to find them, and both of those things are good news,” he said.

His colleague, Professor Robert Harcourt, a marine ecologist of Macquarie University, who is not listed as an author of the study, was also happy.

“This is the first indication of what’s happening with Antarctic blue whales … for a good 20 years. All of the earlier work was based back in the 1950s when we were killing them,” he told the Guardian.

Threatened by whalers

His last point is important to note. Because the Southern Hemisphere blue whale is a species that has long been critically endangered.

While they were a mystery to the 1851-whalers of Moby-Dick, who were chasing a great white sperm whale, for later generations, they would not remain so. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, when whaling became more advanced, the elusive blue whales also became a target.

The Australian Antarctic Division estimates that the population of Southern Hemisphere blue whales before human-exploitation was around 225,000. Now, before this recent study, their estimate was that below 2000 individuals existed. In the 1930-31 season alone, 30,000 blue whales were killed off the Antarctic island of South Georgia.

In 1966, in the nick of time, blue whales finally received full legal protection from commercial whaling.

So, while Herman Melville (or his protagonist) was wrong about the existence of blue whales, he might have been prophetic on another point. Finishing his paragraph, on mythical whales he wrote:

“I omit them as altogether obsolete; and can hardly help suspecting them for mere sounds, full of Leviathanism, but signifying nothing.”

In the end, to the researchers of the Australian Antarctic Division, the blue whales would remain mere sounds, although very real and well-analyzed sounds.

Ole Ellekrog, Polar Journal AG

More on the topic: