In Greenland, 25 of the 34 critical raw materials for the energy transition are present in significant quantities, and last Thursday the European Union and this country signed strategic agreements to develop sustainable value chains for the exploitation of these resources. The partnership declaration follows a series of bilateral strategic agreements that began in 2021 between the European Union and Canada, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Namibia, Argentina, Chile, Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The European Union hopes to release 300 billion euros through these various partnerships, announcing that it will contribute its expertise in the prospecting, exploration, extraction, processing and refining of materials that are critical to European industry. The aim: secure, sustainable and resilient supplies.

Through this new partnership, the European Union hopes to “engage in close dialogue with Greenlandic society” to “develop joint projects”, “attract investment”, “facilitate trade relations” and “operate in a sustainable manner”. On this occasion, Jutta Urpilainen, European Commissioner for International Partnerships, stated that “the new overseas association decision foresees that approximately half of the total envelope of 500 million euros for the period 2021-2027 will be devoted solely to the Union’s cooperation with Greenland.”

Florian Vidal, a political science researcher, is a member of the “Métaux Stratégiques” research group, funded by the French National Research Agency. He is currently based at the The Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø, and collaborates with the Institut français des relations internationales, Université Paris Cité and the Académie militaire de Saint-Cyr. Here, in an interview for PolarJournal, he outlines the contours of this key agreement for the development of the EU and Greenland, where “everything remains to be done”, and breathes his forward-looking vision onto this blank page of high latitudes.

What was the context for these mining agreements?

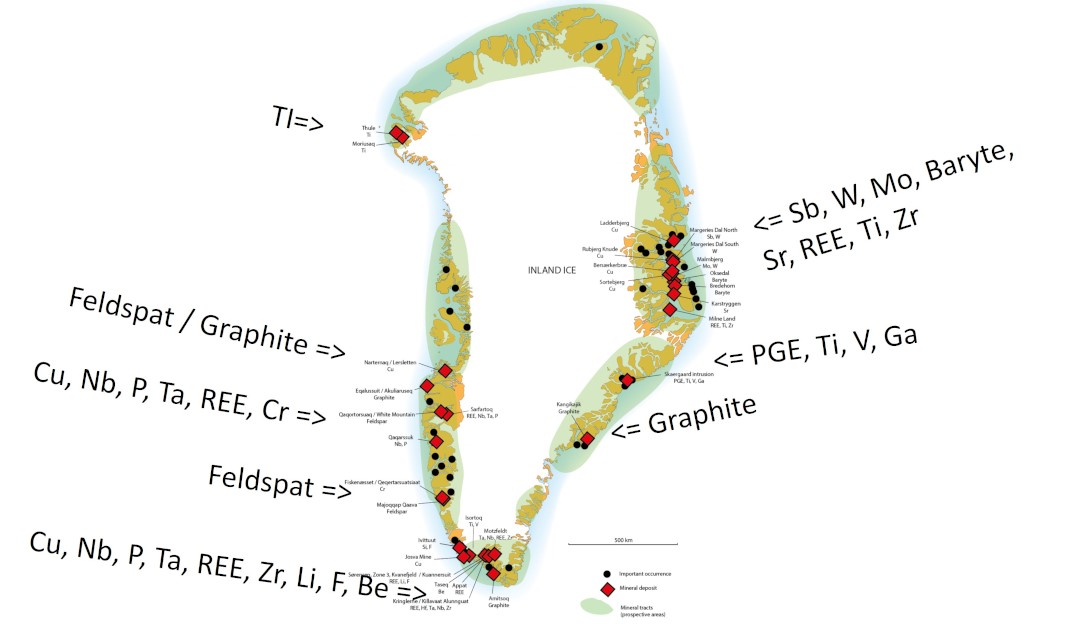

Discussions on the mining issue between the European Union and Greenland go back several years, and form part of the European strategy of reindustrialization as part of the energy transition, with the aim of reducing the risks of dependence on China. In particular, the need to secure certain critical metals, including rare earths, copper, cobalt and other minerals held by Greenland. Geologically speaking, the island is very rich, comparable to northern Russia or northern Canada. If you look at a map, Greenland is in a friendly zone, in the NATO bubble.

This declaration of partnership is in line with Europe’s mining policies in the Barents region, with Finland and Sweden. Similarly, the “Green Alliance” strategic agreement signed this year between Norway and the EU is part of this industrial policy of ecological transition. A similar agreement has been signed with Japan for 2021. It’s interesting to see what ecosystem the EU intends to create in terms of a value chain for mining resources. It would also be part of a dynamic whereby Greenland would become economically anchored to the European Union.

Today, Greenland’s main activity is fishing, and they are trying to develop tourism to diversify their income. In the end, Greenlanders remain dependent on Danish subsidies, which amount to just under 500 million a year. The idea of developing mining activities would, in essence, also be to find enough income to claim that famous independence from Denmark.

What is the environmental dimension of the collaboration project?

Last year, the majority of the Greenlandic population was in favour of mining projects, except for uranium and anything else that might be radioactive. In some countries, nuclear power is once again a major issue in the transition, and could become a point of contention or a source of pressure from certain European countries.

There are several political groups talking about the environmental and social risks associated with the mine. Sustainable mining is a concept that is a little difficult for local populations to accept, but one that is being promoted. There are commendable efforts to electrify mining operations. In the case of future operations in Greenland, I think that mining projects will have to be electrified and carbon-free. A company like LKAB is betting on technical innovation, digitization and robotization of mines. Miners are trying to promote the idea of a sustainable mine, one that will respect social standards, with technologies that will support workers, to relieve them, and obviously compatible with environmental protection.

And this is where the EU has a card to play. In terms of acceptability, it would be easier if there were regulations and control measures to use fewer chemicals in extractive activities, for example. EU is trying to distinguish itself on the market from China and the United States, and is aiming for a mine that is as respectful of natural ecosystems as possible. This is a crucial issue! The problem with mining is that you can turn the question upside down, it will always have an impact on the environment. Ultimately, the idea is to reduce them as much as possible, and that’s an important point for Greenland.

Who are Europe’s competitors in Greenland?

The negative effect of very high standards is to dissuade investors. If Greenland implements this excessively strict legal framework, mining players will be forced to fall in line. So in the medium term, the aim is to move towards a rapprochement between European and Greenlandic standards, to favour European players over those from the United States, for example. China is more or less out of the picture on the island, while relations between the Nordic countries and China have cooled. But the People’s Republic remains indispensable in the rare-earths elements value chain. Even when extracted in Greenland, these raw materials will have to pass through China at some stage in the industrial process to reach the finished product. Thanks to its industrial expertise and production capacity, China holds a form of monopoly that makes it unavoidable, which is a critical factor in setting up a European value chain.

The United States is a little ahead of Greenland, with economic aid packages in place and companies already prospecting. KoBold Metals, backed by Silicone Valley entrepreneurs like Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, uses artificial intelligence to optimize extraction. They identify the most interesting part of a vein to start mining, so as to get the best part of the deposit right away and then limit waste and energy consumption. They are particularly interested in electrification minerals such as copper, nickel and cobalt, which are needed for electric vehicle batteries. It remains to be seen how the EU will position itself in the face of this competition. Even if the EU and the USA are allies, we mustn’t forget that they are defending their economic and industrial interests first and foremost, and that they are not the ones who will create EU value chain.

What is the time scale between the signing of these agreements and the concrete appearance of an extraction project?

This document is very interesting, we’re starting from a blank sheet of paper. Today, there are two active mines, titanium and ruby, and after that, everything remains to be done. One of the problems inherent in any exploitation of natural resources is the price of metals. If the market price of a metal like copper is on the rise, investors are bound to be interested in exploiting the copper reserves in Greenland, and in financing an extractive project in this area despite all the technical difficulties. Then there’s the question of the lack of infrastructure, because without it, it’s hard to imagine large-scale mining on the island.

But beyond the infrastructure that will be required – ports, roads or rails – the most difficult issue is human resources. The island has a population of around 50,000; with these agreements, the population should benefit from the economic spin-offs and job creation, so these people need to be trained. It will be necessary to invest in training courses and enable Greenlanders to attend specialized universities, such as the one in Luleå, Sweden. Today, these resources meet the needs of transition, but it’s a long road that will take at least 15 or 20 years.

Interview by Camille Lin, PolarJournal

Find out more about this topic: